By Kaelin Jewell

I want to take a break from Gephi, spreadsheets, network analysis, and prosopographies to reflect on the recent acts of violence and destruction that have begun to rid Syria and its neighbors of its cultural heritage and how digital tools are attempting to ease these losses.

As many of us are acutely aware, the ongoing armed conflict in Syria has led to an international humanitarian crisis. Alongside the human cost of all of this sits a cultural one: the intentional demolition and subsequent looting of numerous archaeological and other historical sites. In February of this year, the world was shocked by terrorist videos showing the deliberate destruction of ancient objects at the Mosul Museum in northern Iraq. A month later, news broke that terrorists had attacked the remains of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, also in Iraq. The latest in this series of cultural destruction occurred sometime in late August, and still continues, at the site of Palmyra, an ancient city located in Syria.

In an attempt to preserve the memory of these ancient monuments, which are quickly losing a battle against modern conflicts, archaeologists and art historians have begun to rely on digital tools. One group of these scholars has started Project Mosul, an interactive website that crowd-sources images of archaeological sites and museum objects, which are now destroyed, looted, and/or damaged as a result of conflict and natural disaster. These images are then stitched together utilizing the photogrammetry software Photoscan, which produces a 3D model that can be rotated and is fully zoomable.

With the recent destruction at Palmyra, an archaeological geometrician named in the UK has started a similar project called Palmyra Photogrammetry. The project’s mission is simple:

“I am looking for people’s holiday photos from Palmyra, before it’s deliberate destruction by extremists. Using these I can build a 3D model of the ruins.” -Conan Parsons, Palmyra Photogrammetry.

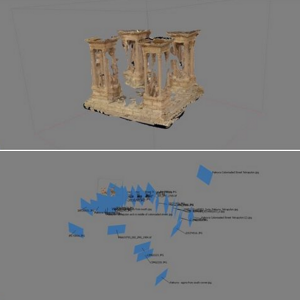

According to his Facebook page, Agisoft, makers of Photoscan, have donated the software and Project Mosul has agreed to host the finished models. Here is his prototype of Palmyra’s Tetrapylon, which marked one of the ancient city’s intersections, created using crowd-sourced images:

As with the reconstructions found on Project Mosul, the Palmyra models will only get better as more photos are donated. One caveat to these donations is they should consist only of digitally-captured images. Because digital cameras create image files that contain meta data such as focal length and ISO, this allows Photoscan to calculate positions and distances of each image relative to the object or monument. Unfortunately, this means that analog photographs taken of these vulnerable or now-destroyed sites prior to the widespread use of digital photography are more difficult, but not impossible, to use. These technical considerations aside, initiatives like Project Mosul and Palmyra Photogrammetry are becoming a popular way that people outside of the academy can help scholars to preserve vulnerable cultural heritage across the world.

Read more at NPR.