When the planning of Charles Library began in 2013 there were literally hundreds of design considerations and decisions to make. From where to locate service units to the configuration of service desks to the technology in instruction rooms, a multitude of design proposals needed vetting and final decisions. Among those many design factors and features, there was only limited discussion of how biophilic design could be incorporated into the planning of the new library building.

Despite that, Charles Library ended up with one of the most significant examples of biophilia that can be designed into a building’s structure – its green roof.

Even though the greenery of plants is conspicuously absent within Charles, we are fortunate to have an amazing display of biophilic design – one that is unique among academic libraries. While we primarily engage with the green roof as part of our fourth-floor experience, it is important to recognize the entire roof of the building is covered in plant life. Here is a photograph of that rarely seen upper-level green roof – quite impressive!

Biophilic design is a simple concept. It is the inclusion of elements of nature into designed structures, whether they be houses, retail shops, hospitals, hotels or even libraries. Adding plants to our built environment is one obvious form of biophilia. A lesser one might be Charles’ extensive incorporation of large windows. Providing these external views of nature, such as it exists in our densely population urban environment, is another way to incorporate biophilic design elements.

Charles’ terrace could be included in that definition. Libraries often incorporate plants, trees, water ponds, fountains and other examples of nature into their outdoor spaces, when available. When they are not, everything from small potted plants to large plant walls bring nature into our physical spaces. Here is an example of interior biophilic design from Penn State’s main Pattee Library after its most recent renovation in 2019:

On regular walks through Charles Library fourth floor, I observed that areas proximate to the green roof, be they study rooms or tables, were most frequently occupied. In the spring of 2022, I serendipitously discovered an article about biophilic design, which up to that point was an unknown topic to me. It made me wonder if there could be a connection between the green roof and students being drawn to it. I become curious about the possible biophilic design qualities of the green roof and how it might affect a student’s study space choice. The green roof was designed into the building for its sustainability features. Did the architects also intend to leverage the roof to provide the benefits of biophilic design?

The primary value of biophilic design is wellness. Whether it invites us to relax, achieve calmness, meditate or practice mindfulness, focus or simply smile, inserting nature and greenery into our built spaces does us physical and mental good. Research done at health care facilities suggests that patients exposed to biophilic design heal more quickly, have improved vital signs like lower blood pressure, all of which results in shorter hospital stays. As the current mental health crisis among college students is of great concern, anything we can do to provide spaces that contribute to wellness is of benefit. These values were reinforced at our fall 2022 Designing Libraries Conference, where a team of architects presented on well buildings. This session spoke to the importance of biophilic design’s contribution to the health and well-being of a well building’s inhabitants.

To better understand the possible connection between our green roof and student preference for study spaces, I constructed a simple survey instrument to gather information about student preferences for study space on the 4th floor of Charles Library. Nancy Turner and Jackie Sipes reviewed my survey instrument, and offered feedback and insights on what might work best to obtain useful results. We also discussed possible strategies for the distribution and collection of the surveys. How might we get the survey to students at the point of relevance without disturbing their study? There were several possibilities – all with potential challenges.

With Andrew Diamond’s assistance, we decided to hand distribute a paper survey to students as they studied at tables and cubicles on the fourth floor. The survey instructions indicated that if they chose to respond, students should leave the survey on the floor. Andrew then waited approximately 30 minutes after the distribution to collect completed surveys. This method was used multiple times during a two-week period near the end of the fall semester. In a second phase, during February 2023, students in study rooms were targeted. Again, paper survey forms were made available for students to complete and leave for later collection. This method yielded 209 surveys usable surveys, 158 from students sitting in open study areas and 51 from students in study rooms. Andrew then transferred the data from the paper surveys to an online form.

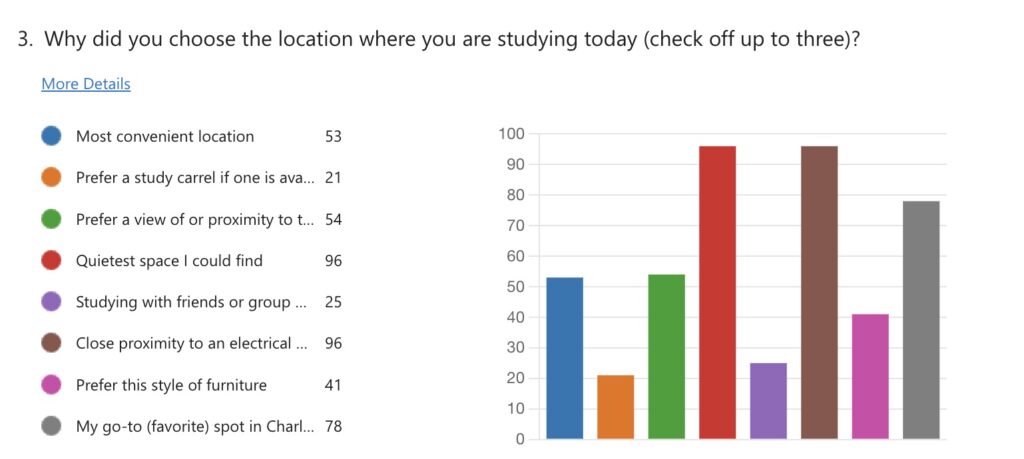

After analyzing the survey results, it appeared that there was a modest connection between the green roof and student study space preference. Students were given a list of eight factors and asked to rate the importance of each of those factors in their study space selection. The green roof was the fourth highest ranked factor, falling below (in rank order) quiet, access to an outlet, and “my go-to spot. “Most convenient” was a close fifth factor (See Fig. 1):

Figure 1. Why did you choose this study location?

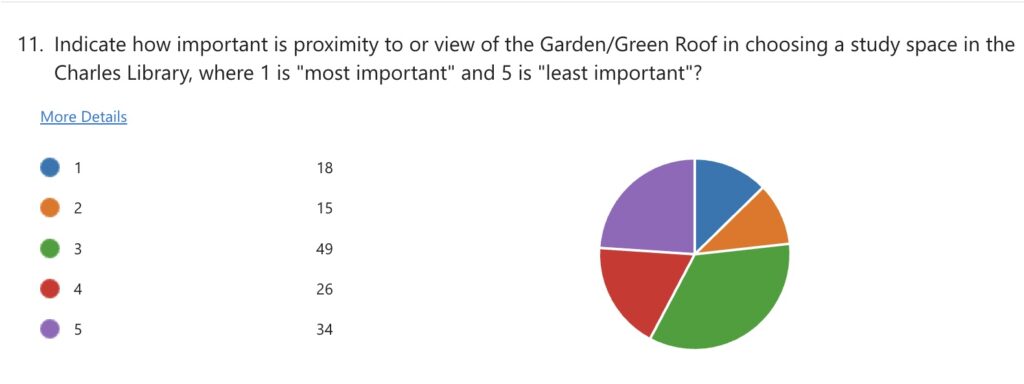

Then students were asked how important several study space features were to them in choosing their preferred space. For the green roof, a lesser number of students identified it as important in choosing a study space compared to other features (see Fig. 2):

Figure 2. How important is a view of the green roof?

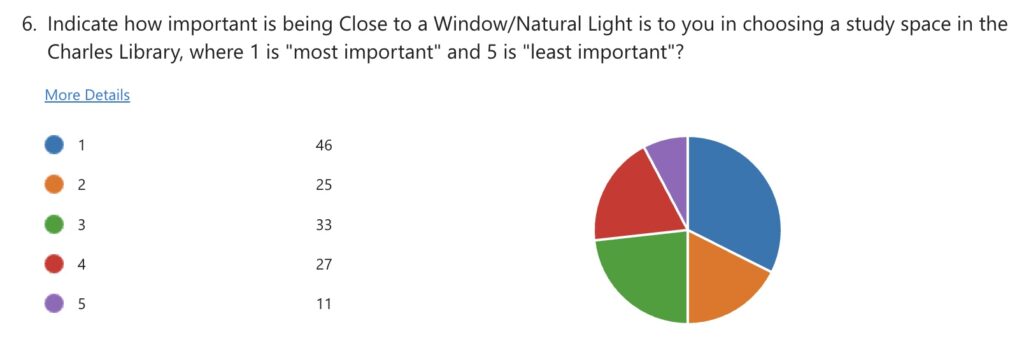

However, when asked a similar question about proximity to a window or natural light sources, the response was quite different. A significant number of students, over seventy percent, indicated it was important to their choice of study space (see Fig. 3):

Figure 3. How important is being close to a window or natural light?

My big take away from this research is that we should not discount or underestimate the important of the biophilic design features of Charles Library, the primary two being our unique green roof and the presence of abundant natural light and outdoor views. In the future, the addition of seasonal planters to the terrace could add a third biophilic design element.

While quiet and device charging are significantly important factors in student preference for study space at Charles, we have a great opportunity to further capitalize on the benefits of biophilic design. Based on this study, I would advocate for the addition of more greenery around the building. Even artificial plants, given concerns about the maintenance of real ones, could contribute to student and staff wellness.

As a next step I plan to do some additional survey collection in later spring and summer months when the green roof is in full bloom. The responses may differ when the green roof is at its peak as a home for bio-diverse plant life, pollinators, and small birds It may also be of interest to conduct the survey on other floors to see if access to natural light and outdoor views is a factor there – or perhaps not so much.

Assessing our services and resources to understand how they impact those who use them should always be at the core of our mission. In doing so we improve our capacity to advance the success of our students, researchers and instructors. It ultimately depends on our capacity, willingness and drive to act on what we learn from assessment as we strive to design better library experiences.

Contributed by Steven J. Bell

Acknowledgements

- Many thanks for Andrew Diamond for his assistance with the distribution and collection of surveys, as well as the input of data into the online survey form.

- Kudos to Evan Weinstein for sharing aerial photos of the upper-level green roof.

- Survey question feedback and suggestions from Nancy Turner and Jackie Sipes were greatly appreciated.

- Thanks to Temple Libraries colleagues who stopped by at ACRL to visit my poster session and share their comments and questions.

Select Readings on Biophilic Design

Berg, Nate. If Your Hospital Suddenly Feels More Like An Apple Store or Greenhouse, Biophilic Design is Why. Fast Company News March 14, 2022

https://www.fastcompany.com/90730709/if-your-hospital-suddenly-feels-more-like-an-apple-store-or-greenhouse-biophilic-design-is-why

Gierbienis, Marcin. Application of Biophilic Design in Contemporary Library Architecture. International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference : SGEM; Sofia, Vol. 19, Iss. 6.2, (2019). DOI:10.5593/sgem2019/6.2

Gillis, K.; Gatersleben, B. A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings 2015, 5, 948-963. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings5030948

Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. https://www.worldcat.org/title/nature-by-design-the-practice-of-biophilic-design/oclc/103089243

O’Keefe, Sean. Biophilia in Education. Interface November 30,2022 https://blog.interface.com/natural-selection-biophilia-in-education/

Salih, K.; Saeed, Z.O.; Almukhtar, A. Lessons from New York High Line Green Roof: Conserving Biodiversity and Reconnecting with Nature. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010002

Schwab, Katherine. What is biophilic design, and can it really make you happier and healthier? Fast Company News April 11, 2019

https://www.fastcompany.com/90333072/what-is-biophilic-design-and-can-it-really-make-you-happier-and-healthier

Tekin BH, Corcoran R, Gutiérrez RU. A Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework of Biophilic Design Parameters in Clinical Environments. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 2023;16(1):233-250. doi:10.1177/19375867221118675