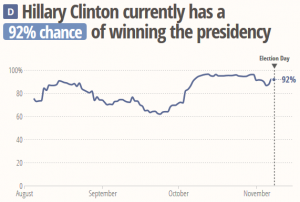

The recent election demonstrated in a powerful way the limits of data, in this case a multitude of polling numbers, towards understanding, or planning, for our future.

As an assessment librarian who counts on numbers to tell a story, I could not help but take this “failure” to heart. In our talk of data-driven decision making – what are we missing? Are we not asking the right questions? Or do our lenses (rose-colored glasses?) prevent us from seeing the whole picture?

I touched on this topic at the recent Charleston conference, where I participated in the panel Rolling the Dice and Playing with Numbers: Statistical Realities and Responses.

I discussed balancing the collection of standard library data elements over time, in order to discern trends, with the changing nature of metrics required to provide a meaningful reflection of the 21st century library’s activities and resources.

Last year, the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) and the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL, ALA) formed a joint advisory task force to suggest changes to the current definitions and instructions accompanying the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) Academic Libraries (AL) Component.

For example, the IPEDS instructions for counting e-books originally said to “Count e-books in terms of the number of simultaneous users” – a problem if we have a license with no access restrictions. Another example is IPEDS’ request that libraries NOT include open access resources, including those available through the library’s discovery system. Not only can this be a difficult number to collect, but counting only the resources “we pay for” goes against the library’s value of making available quality, open access resources to its community.

A continuing discussion on library liservs is related to whether our traditional metrics were “meaningful”. The question was prompted by the publisher of Peterson’s College Guides requesting we report a count of a library’s microforms. We must ask ourselves, “What sort of high school student selects a school based on the library’s collection of microfiche?”

Increasingly, I am frustrated by the “thin-ness” of our metrics, the data that we use to measure ourselves and our success. Not just that it doesn’t tell a robust story. But it also seems to pigeon-hole us with an out-dated notion of what the library does and the service it provides.

Usage metrics are proxies, but are not measures of success. We need to dig deeper. Our instruction statistics demonstrate growth in sessions and students served. Yes, we reach out to faculty and we may be asked back into the classroom. But are we able to demonstrate real learning? How are we demonstrating effectiveness? For instance, we might be more deliberate and systematic in collecting data related to our partnerships with teaching faculty – developing better course assignments; end of year feedback loops on student learning. These are harder, a little fuzzier, but arguably more important, measures of our library work.

We have been having this discussion in academic librarianship for quite a while now. How do we get beyond input and output measures to determine what our real impact on learning is. Yet the best we seem to be able to do is connect the inputs and outputs to other pieces of data, such as a GPA. If true learning is a permanent change in behavior (that’s the way one of my ed tech instructors put it) or thinking, how do we determine the extent to which the work of the library or librarians contributed to the change?

To my way of thinking we will likely need to get more integrated into the teaching and learning process. Being embedded in a course is a good start, though difficult to scale. Perhaps there are some possibilities with learning analytics where librarians may have an opportunity to get called in when a student is at risk and needs extra support for a research assignment. The impact of direct intervention, where it keeps a student from failing a course, could be an indicator of value.