By Jacob Wolff

Whether you picture Highway 66 as a semiotic or literary landscape, that neon-lit drag shared by Jack Kerouac and Denise Scott Brown is worth revisiting.

It’s, of course, immortalized as “the Mother Road, the road of flight,” in Steinbeck’s redemptive tome, The Grapes of Wrath; celebrated for consumer kicks by the ever velveteen Nat King Cole; reimagined as a countercultural escape by Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider; and salvaged by Pixar in 2006, a symbol of small-town charms in a fast-pace world. Highway 66 is an icon of America. As Jean Baudrillard, the preeminent theorist of signs, put it in his America: “they have a Democratic culture of space… …Its definition is spatial and mobile” (102).

My digital mapping project excavates historical data from old maps, oral histories, and lesser-used archives to understand how the ruins of the Mother Road became a monument to people on the move.

The Mother Road

Highway 66 gets plenty of attention from historians of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, but they largely focus on the origin and destination rather than movement through the entire landscape. Caused by the ravages of hyper-productive agriculture, soils turned to dust in the Oklahoman heartland so family farmers moved out west, only to face down vigilante mobs and fascist ranchers in California’s Inland Empire. Heroic artists, then, in the employ of FDR’s Works Progress Administration, documented the undemocratic spirit of California Dreams to amass public support for a national New Deal.

But we’ve missed the crucial experience of migrant mothers along the way. On the border between Texas and New Mexico, one federal writer overheard an “old-timer” quip about an unfriendly welcome for motorists crossing state lines.

“Just watch those cars whiz from one state to another,” said an old-timer. “I bet they don’t know when they cross the line.”

“Well, if they don’t,” spoke up an old lady, “the Port of Entry officials will make ’em pause long enough to take notice.”

Marie Carter, 15 March 1937

So, when considering these interstate border checkpoints between Oklahoma and California, what more do we learn about material origins of free movement, as both an ideal and experience, along historic Highway 66?

Critical Geographies of the Dust Bowl

I look back from the enduring myths of freedom on the open road towards tensions in the administrative New Deal records – paving contracts and marketing ploys that don’t jive with police records barring Okies and Arkies from crossing state lines during the Great Depression. Officials in New Mexico simultaneously accelerated construction of Route 66 — the first Federal highway paved fully from East to West — while erecting interstate border checkpoints on every road leading from Texas and Arizona into the state.

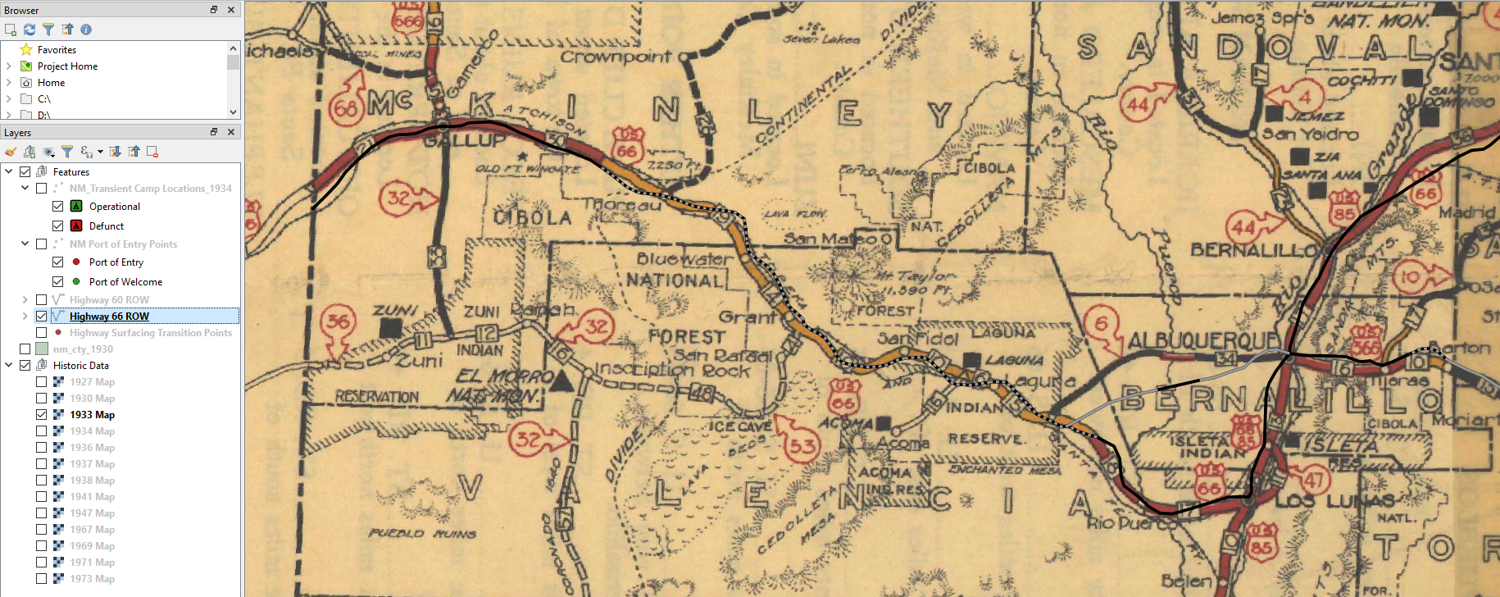

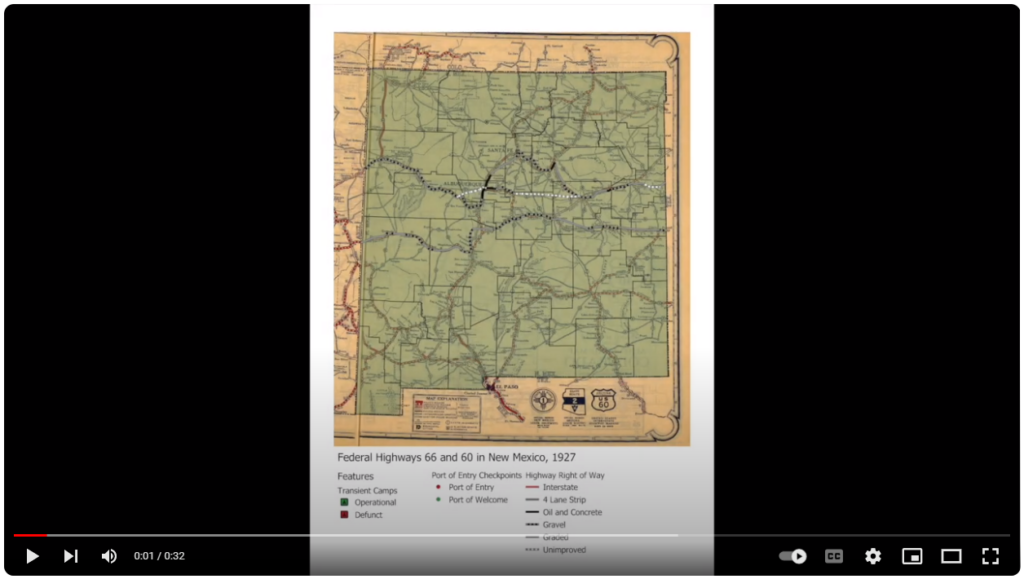

As I described in my previous blog post, counter-maps can help readers visualize “alternative, ideally better, possibilities” by resituating the gaze of institutional map makers within a critical context. This sequence of maps from 1927 through 1941 aims to decode the spaces of mobility as they actually existed – reconstructing the spatial knowledge tourists and transients would have held in mind as they navigated west – and not merely reproduce the geographical imagination that state cartographers hoped to represent.

The inestimable theorist of geography, Henri Lefebvre, reminds us when historicizing space to look for “the antagonism between a knowledge which serves power and a form of knowing which refuses to acknowledge power.” Writers, like Steinbeck, and photographers, like Dorothea Lang, worked with the federal government to make the plight of transient Okies and Arkies legible to Franklin Roosevelt’s political base, but state governments tried to hide any evidence of poverty from the tourists they sought.

Popular travel guides and blogs today republish historical maps digitized by the state Departments of Transportation. These modern agencies are proud of their civil engineering landmarks. But, “Scientists and engineers and bureaucrats are generally rather poor at accounting for or even recognizing the organizing and disorienting power of myth,” social theorist Matt Seybold explains, “and politicians and entrepreneurs and creators are often equally poor at seeing through the myths to a material reality.”

New Deal tourist maps only include data appealing to middle-class motorists: better roads, city centers, Indigenous Pueblos, and natural landmarks.

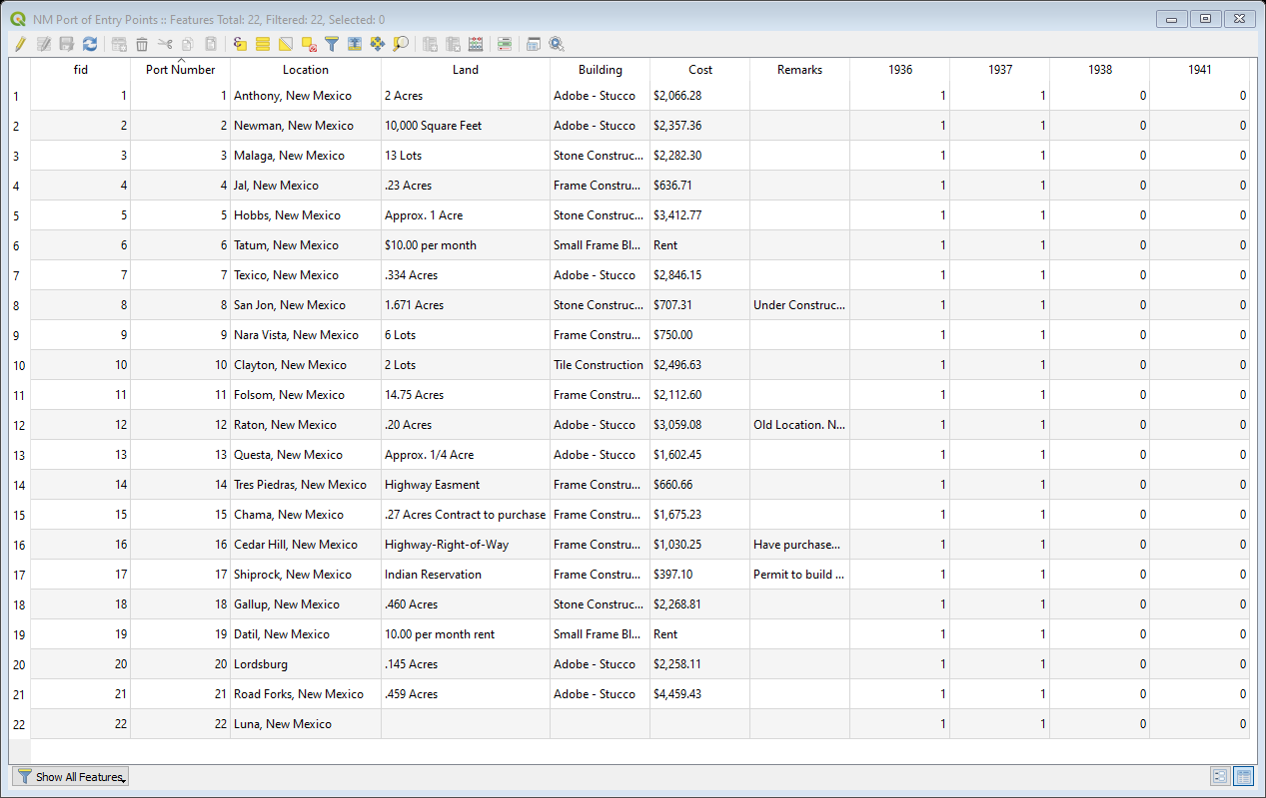

Using those same New Mexico State Highway Maps, I superimposed the locations of all Ports of Entry, rebranded in 1938 as Ports of Welcome, and added transient relief camps run first by the Salvation Army, and later the Civilian Conservation Corps. These data are now organized within QGIS tables, but are sourced from disparate ledger sheets filed across a decade of undigitized governors’ papers in New Mexico. The ephemeral transient camps, even harder to locate in the archives, are pulled from sporadic newspaper references.

With a cash infusion from Washington, the state government in New Mexico could finally afford to pave Highway 66 and much of Highway 60, but the improved infrastructure made it even easier for more migrant families to travel west. In 1935, the state opened “Ports of Entry” ringing New Mexico and the number of transient camps peaked in 1937, the year that paving Highway 66 was completed.

Although this historical record is incomplete, fragmentary evidence suggests that between 1933-1938, the people who most sought refuge along Highway 66 were also hired by state governments to labor alongside local Hispanic and Anglo workers on paving crews. But as transients, the Okies and Arkies were denied free movement over the route.

We don’t find letters from transient laborers filed in the “Port of Entry” folders, but we do find newspaper clippings from disgruntled executives in Chicago alongside angry pleas on American Automobile Association letterhead. Political comics depict armed guards shaking down innocent families in “jalopies.”

Uniformed clerks struggled to differentiate between middle-class travelers and and poor migrants within a motoring public. But rather than abolish these “unconstitutional” and “Balkan” interstate border checkpoints, local New Deal officials in New Mexico increased advertising budgets.

Conclusion

Counter-mapping this iconic landscape immediately before and after the Great Depression with border check-points and relief camps exposes how the ephemeral, yet enduringly popular Highway 66 maps and magazine articles were printed en masse to counteract stories spread by work-of-mouth: freedom, nowhere to be found on the newly open road.

Importantly, Highway 66 is much more than a conduit of a burgeoning consumers’ republic (an empire, even, when accounting for “Indian Detours” through settler-colonial society – another phase of this project). We can see how the Mother Road a workplace just as much as it was a “road of flight” from the Dust Bowl.