Motoring West

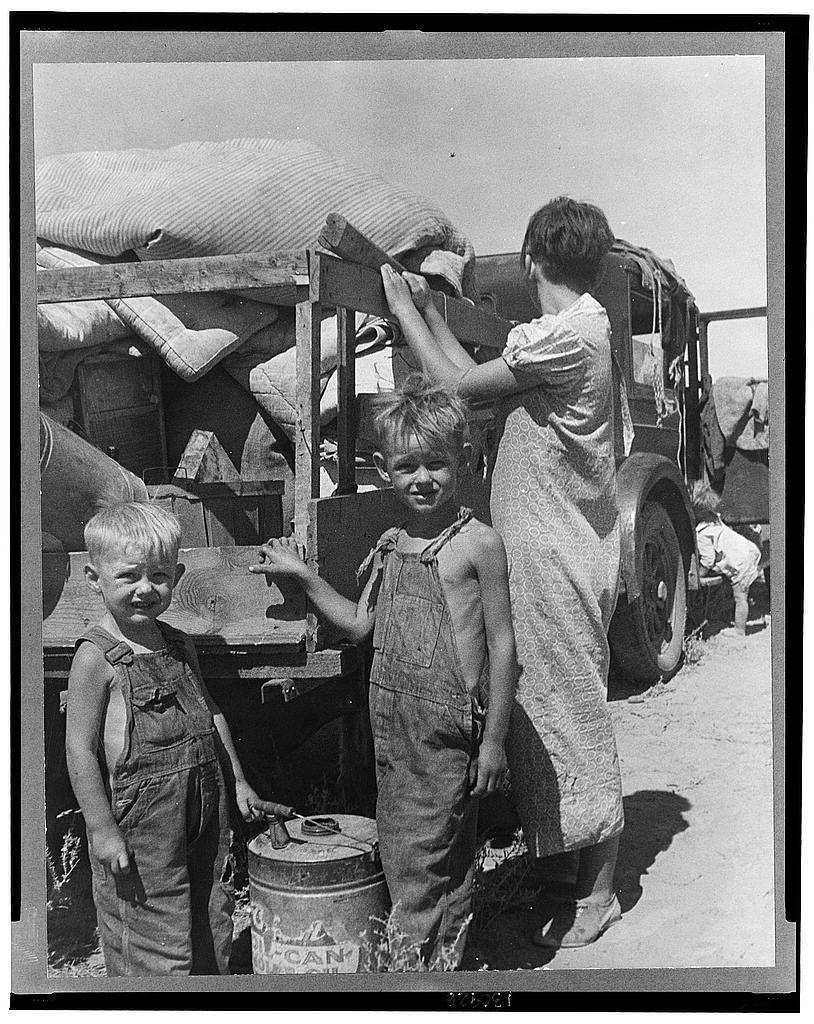

John Steinbeck’s west was no easy refuge from the Dust Bowl. In his 1939 jeremiad, The Grapes of Wrath, the Joads packed their few earthly possessions into a used Ford and motored far from that cacophonous drought wreaking havoc over the Oklahoma plains. Famously, Steinbeck wrote, “66 is the mother road, the road of flight… And, oh, my God, it’s over.”1 But as the Joads neared the orchards of a great Inland Empire, the family found that lawmen and local vigilantes had blocked most roads through California. Still, popular and academic narratives downplay the folks who blockaded state lines to instead celebrate the fortitude of refugees who, against all odds, put down roots.

To set redemptive narratives in relief against the historical realities of exclusion, my digital project for the Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio starts from the icon: highway maps.

These ephemeral documents were published annually by state governments to lure tourists along freshly paved highways, bankrolled by Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). Unlike the glut of bureaucratic reports on paving contracts, traffic counts, and border checkpoints that are stashed away in physical archives, these tourist maps are widely digitized for contemporary motorists who venture off the Interstates in search of any original asphalt from historic Route 66.

The geovisualization project, Countermapping Kicks on Route 66, overlays tourist maps with datasets reconstructed from sparse archival records to demonstrate how the State of New Mexico transformed “ports of entry” into tourist “welcome” centers on the Texas and Arizona lines.

Mapping the Symbolism of Route 66

I am interested in how Route 66 has become both a symbol of freedom and represents the utopian (im)possibilities of an American Dream found out west. These readily accessible maps do, however, pose a methodological challenge for historical research. How can we interpret systematic exclusion using documents intended to encourage circulation? A selective reading of these primary sources can, and has reified heritage narratives, what geographer David Lowenthal defines as “a profession of faith in a past tailored to present-day purposes.”2 The decertified highway is an economic lifeline for rural communities catering to tourists. And, it’s easy to read transcontinental movement as an historical freedom from the old maps because today most patrons of public history can drive freely from Oklahoma to California.

“A map is not the territory,” Alfred Korzybski remarked in his now famous address on the relationship between an object and its abstraction.3 The weight of an ink pressed line might signify one government’s sovereignty against another over the land, but the mapped boundary is not, itself, real. Likewise, as theorist James Scott explains in his germinal Seeing Like a State, “these state simplifications” are “maps that, when allied with state power, would enable much of the reality they depicted to be remade.”4 Highway maps, as advertisements, represented the material progress of public infrastructure linking east to west, and imbued the physical space with new meanings — primarily that states were open to visitors.

Even though the maps encourage free movement of a motoring public, New Deal highway maps are all-too-often taken at face value. In the highway maps produced by the State of New Mexico during the 1930s, for example, political boundaries are pressed in fine-point lines underneath the heavier weight representing federal highways. Color-coded legends depict by 1938 all of Route 66 in a straight line of unbroken asphalt stretching across the state.

Nowhere do any New Mexico State Highway Maps label the controversial “ports of entry” that made Route 66 a household name in the 1930s – long before Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize in 1962 – for blocking extended-families and unrelated people from crossing state lines in the same car.

Countermapping Kicks on Route 66

Countermapping Kicks on Route 66 blends the archival methods of cultural historians with a theoretical framework crafted by geographers. The concept, sometimes hyphenated as counter-mapping, helps scholars and activists identify and realize “alternative, ideally better, possibilities” by situating the gaze of institutional map makers within a critical reevaluation of the social relations that contour our physical or representational spaces.5 Because we have the open-access ability with QGIS to georeference scans of popular historical maps, effectively making analog spatial data legible to modern methods, we can extrapolate and merge multiple datasets – bringing together the cultural ephemera with inaccessible archival documents – to layer the historical boundaries of freedom and exclusion back into representations of Route 66.

Scholars of critical cartography portend that these dynamic, digital geovisualizations expand “the emphasis on the delivery of information to also encompass its exploration,” an essential tool for breaking down prescriptive narratives of official, often analog maps.6 The two-directional decision-making structure for representing various data decenters the cartographer in producing geographical knowledge. Instead, the cartographer curates environmental data for map-users to navigate multiple dimensions of a landscape.

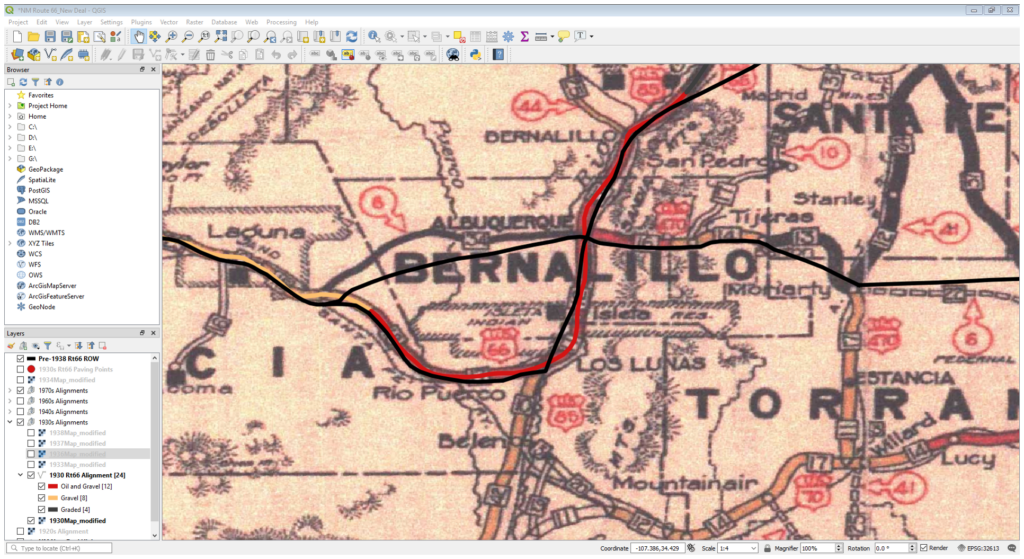

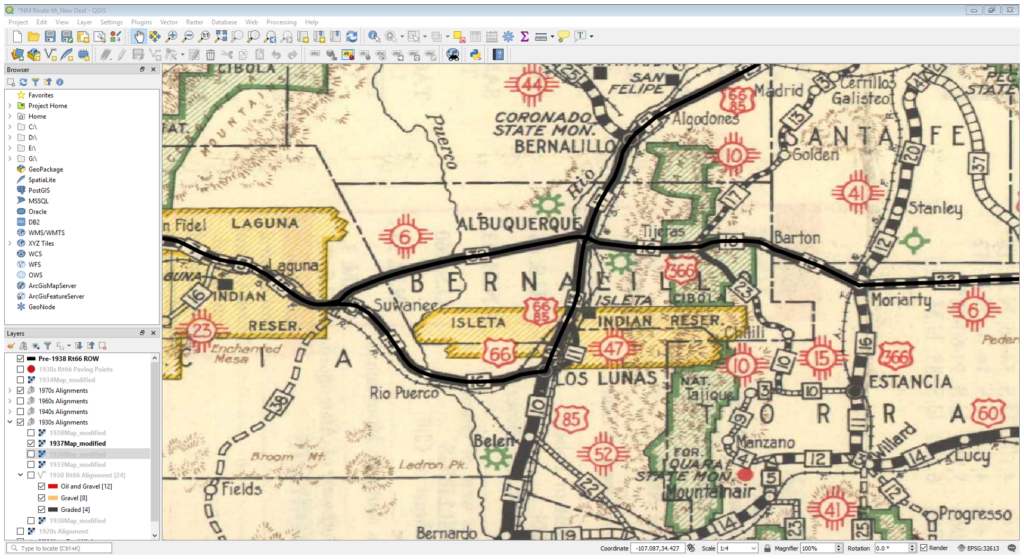

Countermapping infrastructure, state violence, and public protest expands possibilities for audiences to visualize more powerful, radical histories of Route 66 migrations. I have georeferenced (the process of embedding latitudinal and longitudinal points) PNG scans of State Highway Maps from New Mexico during the 1930s and digitized (extracting data from the visual elements) the incremental construction of Route 66 through the decade. This process involves the manual generation of geospatial data in QGIS from disparate sources, requiring contextual knowledge and editorial discretion. If, for example, the location of a road has shifted over time, whether real or a representational error, the data must be cleaned and simplified to accurately characterize spatial changes over time.

Minor visual misalignments, like the analog (1930 basemap) and digitized (1938) segment of Route 66 (solid black line) between Laguna Pueblo and Albuquerque above in Figure 2 can be “cleaned” to fit neatly over a static basemap, as demonstrated by Figure 3. The temporal data stress the most important narrative element determined from reading archived government reports: that Route 66 is straightened to accelerate cross-country travel.

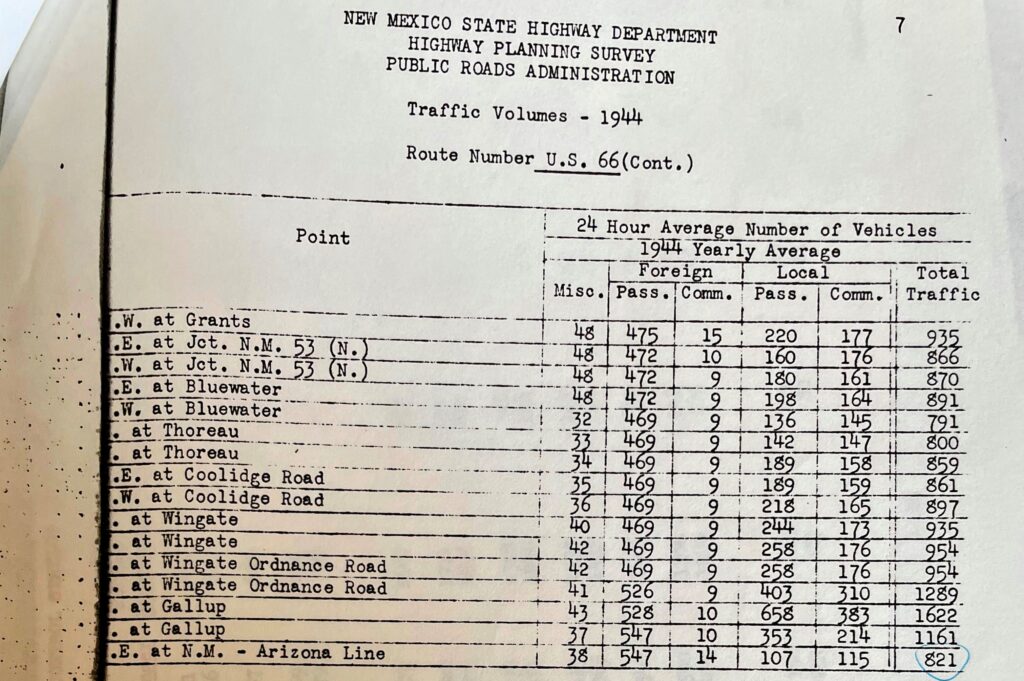

I am also adding metadata to highway segments, including bi-directional traffic volumes by decade. At face value, we can see how quickly state officials modernized the highway, easing the physical conditions of cross-country travel, but state advertisements of modernizing infrastructure are only half the picture.

Evidence of exclusion at interstate boundaries, and the processes through which people came to claim the freedom to move, are found in mostly undigitized archival sources. By layering interstate border checkpoints over tourist maps during the New Deal origins of Route 66, we can learn how middle-class vacationers from the Midwest elicited the most sympathy from liberal public officials in the Southwest.

In the coming months, from the University of New Mexico’s Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, I will add locations of the “ports of entry” to the basemap and broaden the visual frame of the digital map of New Mexico to include the Midwestern places from where middle-class motorists protested the checkpoints. This data is located across disparate collections held by the New Mexico State Archives and the University of New Mexico’s Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections.

Narrating Exclusion

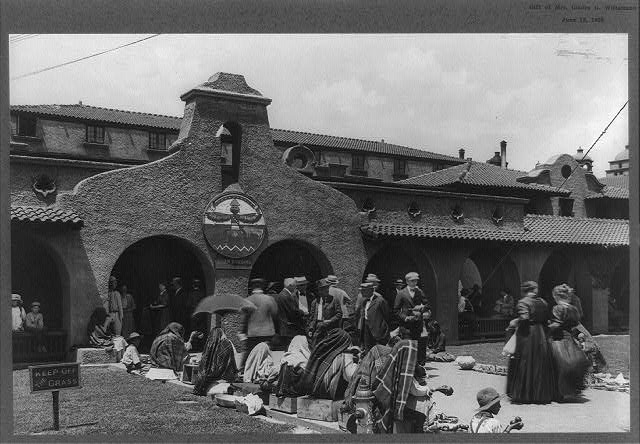

Until 1937, state laws barred extended families and friends from entry in the same automobile, Dust Bowl refugees be damned. Smiling clerks replaced armed guards at rebranded “ports of welcome” only after disgruntled guests, lampooned New Mexico for advertising “unrivaled natural scenery” and “western hospitality” while shaking down travelers for “license receipts” and birth certificates.7 By mapping the violence of interstate border patrols against migrant Americans over a history of tourism, this digital map reframes Dust Bowl mobility and highway modernization not as a gradual democratization of space based on the ideals of full citizenship, but as a byproduct of consumer politics.

The visual focus, too, foregrounds the places in between the East and West coasts. While the Los Angeles Police Department has captured some scholarly attention for “Bum Blockades,” patrolling California borders until New Deal photography like Dorothea Lang’s Migrant Mother won public favor for Okies, the New Mexico “controversy” raises doubt about the durable solidarities of whiteness that allowed Okies to integrate, albeit slowly, into the greater, Golden west.8

Through countermapping, we learn how freedom on the open road is only partial. It was, in large part, an affluent middle-class from out-of-state who coerced public officials in New Mexico to reopen interstate borders based on a consumer ideal rather than as a universal right of national citizenship.

References

- John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath: Complete and Unabridged (New York: Bantam Books, 1939), 126-128. ↩︎

- David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), x. ↩︎

- Alfred Korzybski, “A Non-Aristotelian System and Its Necessity for Rigour in Mathematics and Physics,” address given to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 28 December 1931. ↩︎

- James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 3. ↩︎

- Craig M. Dalton and Tim Stallmann, “Counter-mapping Data Science,” The Canadian Geographer 62 no. 1 (2018), 93-101. ↩︎

- For more on critical cartographies, see: ACME, An International Journal for Critical Geographies, Vol. 4 No. 1 (2005): Special Issue: Critical Cartographies ↩︎

- David Kammer, “Historic and Architectural Resources of Route 66 through New Mexico” of the National Register of Historic Places (Washington, DC: Department of the Interior, 1993), 62-63. ↩︎

- James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991) and Peter La Chapelle, Proud to Be an Okie: Cultural Politics, Country Music, and Migration to Southern California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Bill Lascher, The Golden Fortress: California’s Border War on Dust Bowl Refugees (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2022). ↩︎