By Mikayla Brown

Introduction

Over the past few years, conversations regarding the global repatriation of cultural artifacts have garnered substantial attention. These discussions have ignited debates throughout Western nations, focusing on the topics of repatriation and restitution as crucial components to confront and address the legacies of colonialism. Among these debates is the international initiative for the return of the Benin Bronzes, which has emerged as a pivotal point in reconciling historical injustices and reclaiming cultural heritage. Repatriation has gained notable attention in mainstream pop culture, as illustrated in the memorable moment from the film Black Panther (2018). In this pivotal scene, a British Museum guide mistakenly attributes a mask as originating from Benin. However, Killmonger (a character in Black Panther) corrects her, asserting that its true origin is Wakanda, and takes steps to reclaim it for his homeland, eventually returning it to Wakanda. Previously dismissed as mere collections that belong to all of humankind (Cuno, 2010), this scene exemplifies why it is crucial to recognize the true history of looted artifacts. The “museum heist” scene places debates about repatriation into dialogue with superheroes, agency, and misrepresentation, underscoring the urgency of acknowledging the origins and cultural significance of stolen artifacts worldwide.

As a doctoral student in Klein College of Media and Communication at Temple University, my research centers on museums’ discourse, repatriation and restitution initiatives, ethics, and colonialism. Serving as a graduate extern in the Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio and working towards completing the Cultural Analytics Certificate, my digital research delves into the migration patterns of the global Benin Bronzes repatriation initiative. The focus of my digital humanities research lies in constructing a comprehensive dataset, metadata, and map visualization for the Benin Bronzes, contributing a visual layer to my dissertation research. My research is asking, how can we visualize the history of colonialism?

Repatriation of the Benin Bronzes – A Brief Summary

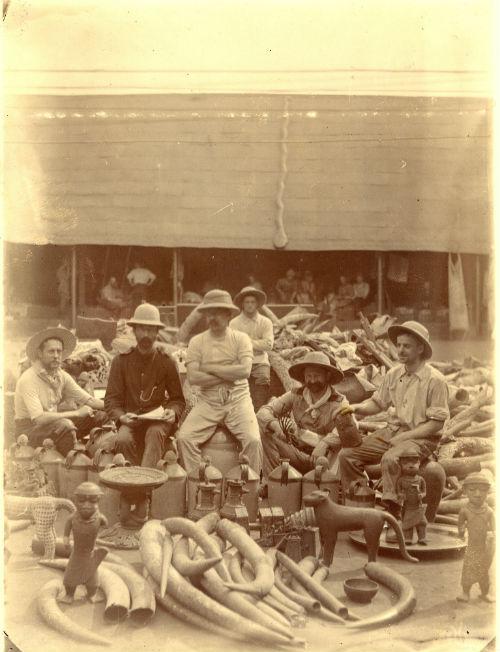

The Benin bronzes are intricate brass and bronze sculptures, originating from the Kingdom of Benin in Nigeria. Dating back at least 500 years, they were created in the 16th century and onwards. These masterpieces were looted from the palace of the King of Benin during the punitive Benin Expedition of 1897 by British forces. This resulted in the widespread dispersal of these artifacts to various museums and private collections worldwide (Phillips, 2022).

Recently, the campaign for their repatriation has gained momentum, fueled by calls for restitution and acknowledgment of the injustices perpetuated during and since The Scramble For Africa and the Benin Massacre of 1897. The troubled history of the Bronzes, which includes international theft, colonialism, and unethical or highly dubious museum curatorial practices, spurred my interest in investigating the ongoing Benin Bronzes repatriation initiative. However, colonialism can be a difficult concept and phenomenon to understand, at once; it is ancient and modern, concrete and abstract. My project will use digital mapping as a technique since it offers a unique lens to navigate the complexities of colonialism and visualize the intricate migration pathways of cultural artifacts that have been stolen, held by foreign institutions, and, sometimes, given back to their originating country. By creating a digital map of the movement of the Benin Bronzes I will illuminate connections between governments, museums, and other institutions, encouraging discussions around repatriation and the ethical responsibilities tied to the return of these cultural treasures.

Starting My Research

In order to visualize the migration patterns of the looted Benin Bronzes, I needed to gain a better understanding of what repatriation is and I needed to become more knowledgeable about the history of the Benin Bronzes. My project began by reading about the history of the Benin Bronzes, what the artifacts are, what their cultural importance is, and how they came to be looted from Benin City and held by Western institutions globally.

I also investigated the status of the Benin Bronzes repatriation initiative and began to draw connections and patterns of their repatriation status across different countries and institutions. After reading through countless news articles and books on the Benin Bronzes, looted art, and repatriation it became clear that the Benin Bronzes is an intriguing case study in the realm of repatriation dynamics, incorporating ethical concerns related to curatorial practices and theft, colonial pillaging, and institutional legacies.

Collecting Metadata

The next phase of my research was dedicated to constructing a comprehensive dataset encompassing historical information on the theft of the Benin Bronzes, along with metadata details about both the artifacts themselves and the institutions currently holding them. This dataset serves as the foundation for the development of a digital map aimed at tracing the intricate migration patterns of the Benin Bronzes.

Compiling this information was conducted manually, drawing primarily from key sources such as Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes (2022), The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence, and Cultural Restitution (2020), The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story Of The Art In Our Museums & Why We Need To Talk About It (2021), and numerous articles on the Benin Bronzes from The Art Newspaper, among many other helpful resources. These sources provided crucial contextual insights into the Benin Bronzes, the history of art theft, and ongoing repatriation initiatives.

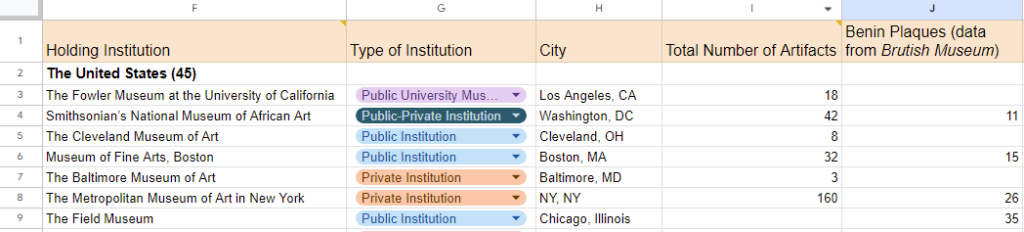

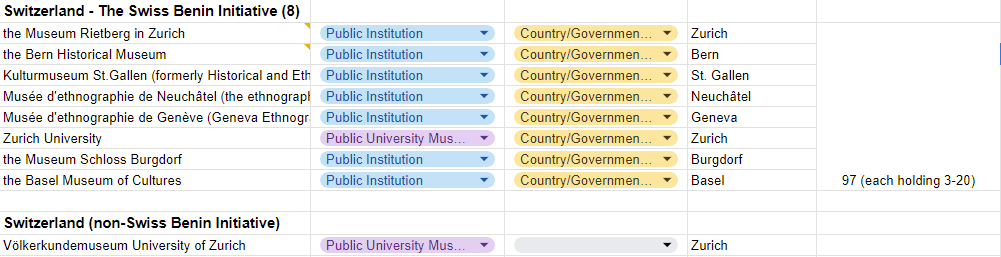

The compilation process involved cataloging countries, institutions, museums, and universities that possess Benin Bronzes. Approximately 160 institutions, ranging from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the Church of England, were identified as custodians of these artifacts (Hickley, 2021). In the United States alone, 23 institutions house looted Benin Bronzes, while England hosts around 46 institutions with similar holdings (Hicks, 2020).

Recognizing the variability in the number of artifacts held by each institution, ranging from five to over 100, I systematically documented the quantity of Benin Bronzes in the possession of each institution. I also gathered information pertaining to the estimated timeframe of the initial looting, the current repatriation status (including details on loan agreements, full repatriation, partial repatriation, ongoing efforts, and lack of progress), and the categorization of each institution based on the five theft categories (garden-variety theft, archaeological looting, wartime pillage, state expropriation, sales under duress/other forcible transfers).

By synthesizing this multifaceted information, my overarching objective is to construct a comprehensive narrative detailing the journey of the Benin Bronzes from their origin in Benin City to their dispersion across the globe through mapping.

Next Steps – Sharing Metadata and Creating a Map

Upon the completion of data collection on the Benin Bronzes, I will upload it to TUScholarShare, a free, open repository that shares, promotes, and archives Temple scholarship to a global audience, with the goal of advancing knowledge and learning. Once the metadata spreadsheet is uploaded, the next step involves importing the compiled information into a mapping software, such as CollectionBuilder or Mapbox, so that I can begin mapping the colonial history of the looted Benin Bronzes.

Subsequently, the mapping process will commence! – Illustrating the trajectory of the Benin Bronzes from their origin in Benin City to various locations across the Western world. Notably, the map will feature color coded lines to visually represent the movement of the Benin Bronzes to various countries and institutions. Additional color-coded lines will depict the institutions that have repatriated the Benin Bronzes back to Nigeria, emphasizing the ongoing repatriation status for each institution. The contextual information that was compiled will also be included as metadata attached to each mapped institution, providing additional context. This mapped visualization aims to enhance the understanding of the complex movement and restitution dynamics surrounding these cultural artifacts. Through mapping, the dispersed Benin Bronzes across the globe can be tracked, cataloged, and presented in a spatial context.

References

Benin bronzes. (n.d.). The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/benin-bronzes

Cuno, J. (2010). Who owns antiquity?: Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage. Princeton University Press.

Hickley, C. (2021, April 29). Global survey: where in the world are the Benin bronzes? The Art Newspaper – International Art News and Events. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/04/29/global-survey-where-in-the-world-are-the-benin-bronzes

Hicks, D. (2021). The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press (UK).

Phillips, B. (2021). Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes (Revised and Updated Edition). Simon and Schuster.

Procter, A. (2021). The whole picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums and Why We Need to Talk about It. Cassell Illustrated.