By T.A. Spiro-Costello

With a basic set of tools and any amount of setting the scene, a game designer can tackle almost any topic. As a cultural critic, I try to hone in on the treatment of contentious topics in media, especially games. By looking at how controversial topics are handled, we can learn a lot about standards of expression, and the expectations of media within the marketplace. For my project for the Scholars Studio, I am going to utilize game design tools in the creation of a game that explores the topic of queer dating. Leaning on design tropes from dating videogames, this project explores the role of uncertainty in attraction and the aspects of the self that are pliable and those that are not.

Tabletop games address difficult topics all the time. Whether it’s greed, disease, betrayal, or terror, games give us tools to play with things we wouldn’t want to experience ourselves. Violence is one example of a difficult topic made approachable through gamified abstractions.

Abstraction reduces troops to numbers and figurines, a commander’s assessments to a roll of the dice, and reinforcements to a matter of moving pieces on a board. Game studies scholar Jesper Juul famously described games as being half-real. Real rules work to provide a system of interaction, while fictional elements set the scene and make it OK for players to experiment because they’re separated from the real world.

Abstraction and the reduction of real (and imagined) concepts into a set of approachable rules can be one of the most profound strengths of the medium. This process of gamification can make any manner of topic approachable with the right care. What follows is an examination of the most common tools games give players to help them understand the world and lessons of the game, with a particular focus on 1) Space, 2) Chance, and 3) Choice.

Space

Games make use of space in order to differentiate. Linear boardgames like Monopoly or Life use their space to show where players are on a path or track. Grid-based boards like Chess or Go have more dynamic movement over a non-linear area. Still other games utilize space as an indication of player commitment.

Space can also be used for organization. Games like Dead of Winter or Cosmic Encounter utilize space to order and represent player interactions. In such instances, the focus is on where the action is, not where those spaces are relative to anything else. These spaces can be increased or decreased, and can measure elements as dynamic as unique actions or simply exist to track movement. Other elements get used to keep track of the state of the game. Scythe and Ticket to Ride make use of the borders of the game to track player progress in key areas.

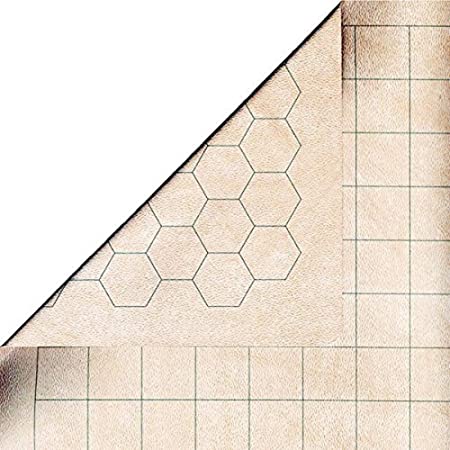

There are many tools to help a player design tabletop spaces. The simplest is paper, which allows for easy and rapid customizability. More durable prototypes can be made using industrial-level tools like a jigsaw or laser cutter. Many designers find that a happy medium is a wet-erase mat, which has enough heft and durability to accommodate metal pieces and dice, but also allows rapid re-drawing of either part or all of the playspace.

Chance

Games like Tic-Tac-Toe and Checkers are games of pure strategy. For these games, outcomes are predictable based on their rules alone. Most games involve at least some level of chance. This doesn’t mean that such games are just luck, as it’s important to remember that courts have decided that Poker is a game of skill. Managing the uncertain is a vital skill both in and outside games.

The two main tools of chance are dice and cards. Dice commonly come in 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 20-sided varieties. Combining multiple die rolls can serve to normalize results, since adding more dice means numbers will trend toward the median result. Extra dice can also make play more dynamic, as when certain rules allow players to roll an additional die.

Dice can be customized to show non-numerical results, but for games that require something other than numbers, cards are often the best option. Cards can be customized to hold either simple or complex information. There can be as many or as few cards in a deck as suit the game. Cards also afford what’s called distributed randomness, where all results will appear in the proportion the game designer intends.

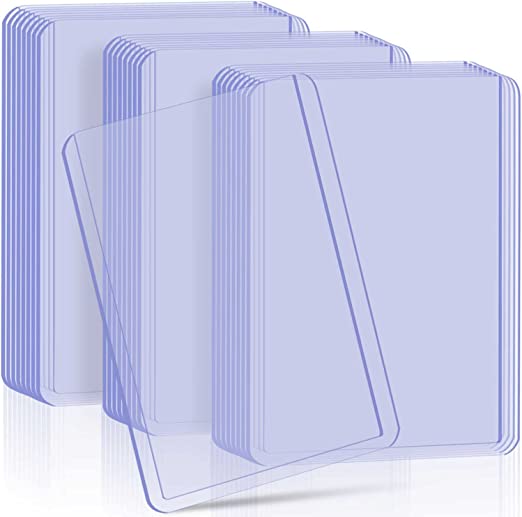

Designers who want to experiment with their own chance elements have numerous options. Random.org has a variety of tools for rolling dice and randomizing lists and more. Dice are readily available online and at gaming hobby shops, and keeping a table of outcomes handy can help standard dice serve for specialized dice. Custom dice can easily be mocked up with spreadsheet tools like Google Sheets. Custom cards can be easily mocked up using cheap card sleeves available in most hobby shops, using standard cards for rigidity and with custom slips of paper inserted to serve as the card face. Card design templates can be used to add additional style to a custom deck of cards.

Choice

Sid Meier famously distilled the importance of play to players making “a series of interesting decisions.” Making a game can be daunting, but one way to simplify the process is to focus on player decisions. Game designers can streamline their process early on by asking the following questions:

“What are the possible actions a player can take?”

“What are the possible outcomes for those actions?”

Decisions can easily be distilled down to action and outcome. Understanding games as emerging from taking one action rather than another, and triggering one outcome versus another, is a simple way of creating a basic gameplay loop. Choices can be based on concepts like space or chance, or they can be as simple as making a wager. Thinking about how player choice impacts the player, the play space, other players, and other mechanics will go a long way toward putting your game in play.

Conclusion

After space, choice, and chance are accounted for, there remains another, potentially more significant concept to address: testing. The iteration process of game design is where the work of play comes to the fore. Here substantial additions and subductions occur, both large and small. It’s these tweaks that often end up defining the game experience for the most casual players.

Games are great tools for both learning and fun. In the spring I will be revealing my game and explaining how these and other gameplay concepts led me to make the gameplay decisions my co-designer and I made.