By Laurie Fitzpatrick

Project Background

I am investigating novel ways to use newly digitized primary sources in my research into the New Sweden colony in early modern North America. This small Scandinavian colony existed from 1638 to 1655 in an area ranging from present day Wilmington, DE to Trenton, NJ, on both sides of the Delaware River. New Sweden is the least analyzed of the four European 17th Century colonizing efforts in North America. The cultural remoteness of New Sweden – wholly 17th Century Scandinavian – presents language difficulties as primary sources are handwritten in Swedish, German, and Dutch. Recent historiography of New Sweden has three separate currents:

• Articles and books written for people with genealogical interest in the colony and its colonizers

• North American historians either exploring transnational themes (political and economic entanglement with other North American colonies) or rehashing historical tropes established by Dr. Amandus Johnson over 100 years ago (Lenape Indians and Swedes ‘loved’ each other, slavery was accidental or unintentional in the colony)

• American and Nordic archaeologists who apply post-colonial analysis arising from material culture theories that explore themes of ‘otherness’ and ‘nostalgia’

My ongoing digital project, a new database of information about New Sweden colonizers, will merge the three separate strands of contemporary historiography into a holistic approach that rejects all teleological and filiopietistic analyses, or the promotion of inaccurate historical narratives. I will collect, sort, and visualize colonizer data from all available sources to investigate instead the agency of individuals who interacted with each other and with colonial leadership.

Building a Database of the New Sweden colony (1638-1654)

Since spring 2019, the Swedish Royal Archives has been digitizing their collection of New Sweden materials that offer information about individual 17th Century Nordic colonizers including their counties of origin, ages, occupations, and pay. Officials recorded brief passages of demographic and ethnographic information about individuals as ship passengers, as company employees in the Governors’ censuses, and as debtors in the company books (Figure 1). In Sweden at that time, Swedish officials kept records of their human capital for reasons similar to those of competing 17th century Early Modern empires.[1] One difference is in the way the Swedes used their colonial projects to build their centralized Swedish state through administering assigned regions in Sweden and in overseas colonies. [2]

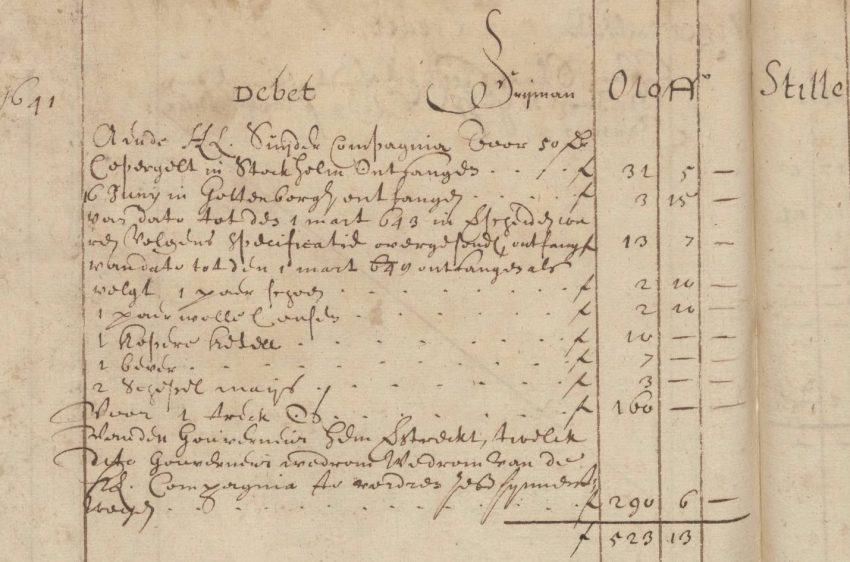

Commissary Hendrick Huygen’s account for Oloff Stille

Figure 1: In this monatgelderbuch (Month money book), Huygen recorded 7 years of purchases for colonizers, including Olof Stille, starting in 1641 and ending in 1648. During this time, Stille received goods valued at 523 Dutch florins and 13 stuivers, worth around $31,000 today. [3] Image courtesy of the Swedish Royal Archives, Kolonier. Kolonien Nya Sverige I, Volume 42, Henrik Huygens monatgelderbuch, page 52.

Johnson used these Swedish primary sources over 100 years ago when he wrote his 2-volume history, The Swedish Settlements on the Delaware, 1638 – 1654. In my research, I consulted Johnson’s history as a secondary source and found he used Swedish primary sources to serve his agenda to promote the great value of Swedish American contributions to the United States. His goal was to elevate Nordic immigrants above European immigrants entering America in the early 20th century, and above African Americans moving from the South to Northern urban centers. When re-examining the Swedish primary sources consulted by Johnson, I found no Swedish American chauvinism or Nordic supremacy in these sources.

A recent genealogist, Dr. Peter Stebbens Craig, used these Swedish primary sources (see link above) to flesh out the lives of individual colonizers who were of genealogical interest to him. He does not, however, pose historical questions using these sources.

For my project, I created an Excel spreadsheet of lists of names from Johnson, available as digitized, optical character recognition (OCR) PDFs of Swedish Settlements that are machine readable. To this I added digitized information from Craig’s genealogical articles published the Swedish American Genealogist and the Swedish Colonial Society News (1990 – 1999 and 2000 – 2014). Much of this Craig material is available online as PDF’s, but not all is in OCR format. Craig included the names of women and children, as well as second and third generation colonizers. For this project, I also included the names of colonizers listed in Henrik Huygens monatgelderbuch to create connections between colonizers and the colony’s commissary.

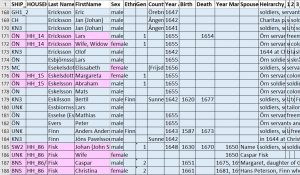

My current database suffices for this first database viability experiment. After I explore my database through visualizations, I will add more data from additional digitized primary sources like Craig and Huygens, including qualitative and quantitative data about the first three generations of colonizers associated with the New Sweden colony (Figure 2). I must also examine Craig’s records (held at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Image of my New Sweden database, in Excel

Figure 2: example of the data I am collecting, currently in Excel.

to establish the reliability of his research before I include more of his work in my data. This Temple Digital Scholars project has guided and refined my understanding of the utility of the information I am collecting, as well as how I can structure my database to permit access to this information. I regard my database as a scaffold I can use to further tease out, organize, and thus employ every scrap of information I glean from the New Sweden digitized primary sources. The results of my data visualization experiments are in my next post: Digital New Sweden, Part 2: Visualizing a Database of New Sweden Colonizers with Gephi.

Please feel free to contact me with questions or comments about this work at fitzpatl@temple.edu

References

Huygens, Hendrick. “Oloff Stille Account 1641 – 1648” in Henrik Huygens monatgelderbuch. (Swedish Royal Archives, Kammarkollegiet, Ämnessamlingar, Kammarkollegiet Handel och sjöfart, SE/RA/522/09/42 (1637-1689) https://sok.riksarkivet.se/bildvisning/R0003349_00052#?c=&m=&s=&cv=51&xywh=-838%2C-20%2C7035%2C3932

Karonen, Petri and Hakanen, Marko. Personal Agency and Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720. (Finnish Literature Society, SKS, Helsinki, 2017).

Willem van Osnabrugge Money in the 17th century Netherlands http://vanosnabrugge.org/docs/dutchmoney.htm

Footnotes

[1] Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen. Personal Agency and Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720. (Finnish Literature Society, SKS, Helsinki, 2017), pgs. 125 and 122. Governors, for example, represented the crown in their region or colony, and were ordered to “cover and assess all aspects of life in the provinces” in their records, correspondences, and reports.

[2] Following the death of King Gustavus Adolphus, Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna proposed Sweden’s first constitution, known as the Instrument of Government, that was adopted in 1634 as the framework for the new Swedish state. A general order of 1635 required detailed and homogeneous instructions for governors to ensure the building and maintenance of the modern, uniform, and harmonious 17th century Swedish state. (Karonen and Hakanen, pgs. 122 and 131).

[3] To get a rough idea of the value of one Dutch florin, multiply that by a factor of 60. From: Willem van Osnabrugge Money in the 17th century Netherlands, http://vanosnabrugge.org/docs/dutchmoney.htm, accessed 11/14/21.