By Tenninger Kellenbarger

Introduction:

As an art historian, I am examining and evaluating the use of the smiting pose in the Aegean Bronze Age while also investigating and tracing the roots of the smiting pose in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Early Bronze Age. My project for the CAC practicum drew upon the evidence available from Minoan Crete and the Bronze Age kingdoms of the Ancient Near East and Pharaonic Egypt. By focusing on the use of the smiting pose in both the Ancient Near East and Egypt, the larger study will track the pose’s use, transference, and importation to the Aegean world and changes made in its form the pose is exported back to the Eastern Mediterranean.

The digital component of my dissertation seeks to create a timeline from a complete dataset of ancient Bronze Age art of the eastern Mediterranean which shows the smiting pose. This will be done to show the stylistic changes occurring between these three areas will act as a visual counterpart to the written dissertation. This blog post serves to give a brief introduction to the creation of the digital portion of my dissertation. I will give detail pertaining to data collection, management, and analysis.

Battle of Glen signet ring CMS I no 16. Shaft Grave IV, Grave Circle A, Mycenae.

Why I chose this project?

Presently, the smiting pose in its developed form is only seen on signet rings, seals, and sealings during the Late Minoan (LM) I-II period. Later iterations of this pose are found in the Late Helladic (LH) III frescoes from the Palace at Pylos.

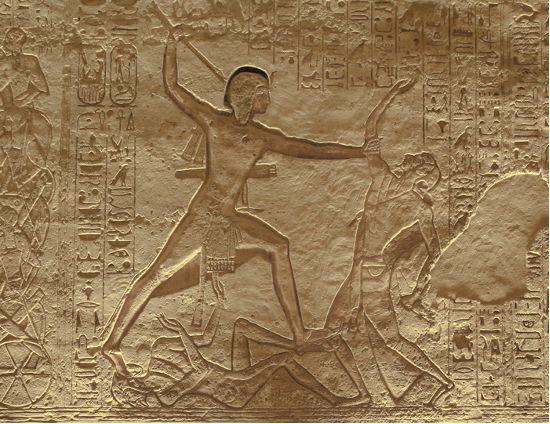

This figural form only appears in the Late Bronze Age on Crete, where it was most likely imported from the Eastern Mediterranean. This image of the smiting pose has a long history in Egypt, and it is also known in kingdoms in Anatolia, the Levant, and Mesopotamia.

Once the use of the smiting pose of man versus man declines in the Aegean, there is a noticeable change in the representation of the smiting Pharaoh in Egypt. This change will be visually tracked and cataloged in hopes of a better understanding of how this pose was effective throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. The stiff image of the smiting Pharaoh in Egypt after LM II (roughly dynasty XVIII in Egypt) begins to change and becomes reminiscent of how the Aegeans structured this pose. The following periods in Egypt continue this tradition, with examples extending into the Iron Age.

| South wall of the temple at Abu Simbel, Ramses II slaying two Libyans. |

This project concludes my work on Temple University’s Cultural Analytics certificate program. I began courses in Fall 2019. This practicum course has allowed me to complete a portion of the digital component of my forthcoming dissertation. For more information on the Cultural Analytics program, please visit https://library.temple.edu/categories/cultural-analytics-certificate-program or email ca-program@temple.edu for questions and further information.

Collecting Data?

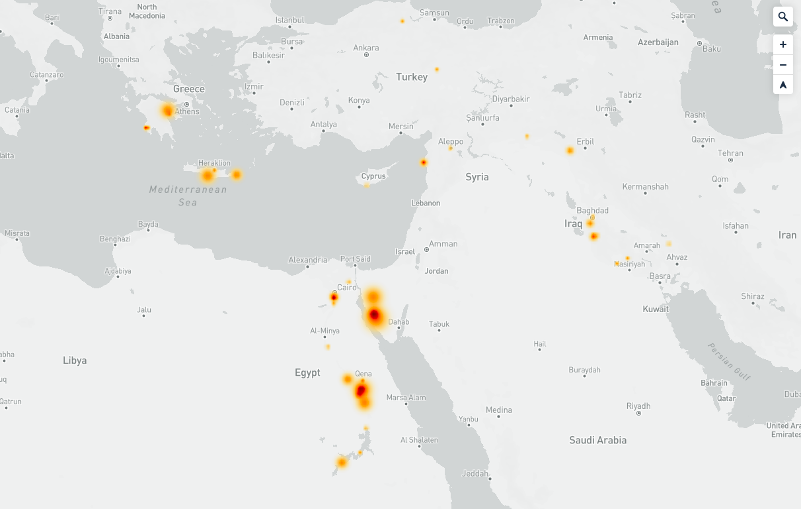

My original plans for my digital project focused on creating either a timeline or a map locating the material culture from their find spots. As this study focuses on archaeological evidence, mapping can become an issue when provenance is unknown, primarily when not attributed to a specific context. Because of this, I needed to shift my focus and create a digital product that would best serve my dissertation topic.

Thus, my efforts turned to the timeline where these objects have been dated stylistically. As I am working through my Ph.D. in Art History through Tyler School of Art, I can view the pieces in an iconographic study taking a formalist and semiotic approach. That is not to say that I won’t include a digital map down the line of this project, but for showing the poses stylistic transformation throughout the Bronze Age, a timeline best serves this purpose.

I created the dataset using examples from Pharaonic Egypt, the Kingdoms of southwest Asia, and the Aegean spanning from the Final Neolithic (roughly 4000 BCE) to the end of the Bronze Age (about 1150 BCE).

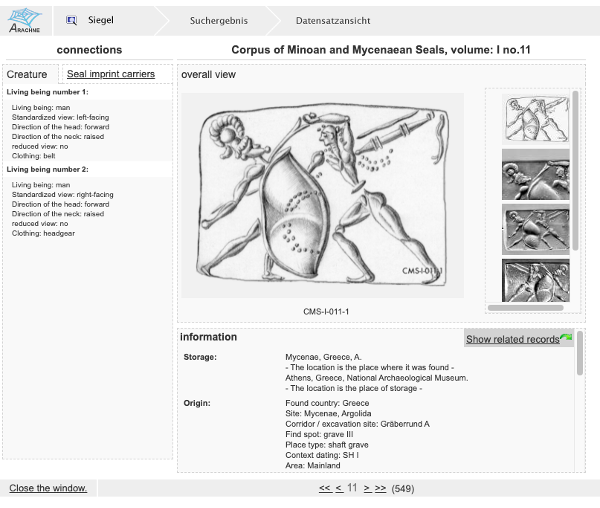

Included in each entry will be categories pertaining to the region, ruler/ pharaoh (if applicable), weapons seen, and notes on the presence of gods (if they are represented), as well as any other further comments. Data was gathered from the following museums and publications: the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Berlin Museum, Louvre, the Israel Museum, The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Papadopolous 2006, and Bestock 2017. For material culture coming from the Aegean, information was gathered from the online databases Arachne and IconAegean.

Arachne Database showing the Corpus of Minoan and Mycenaean Seals

After the data was collected, a digital timeline was created by importing the data into the correct formatting used by Knightlab and their Timeline JS program. Pictured below is what the data looked like when in google sheets as compared to my CSV file.

Conclusion and Moving Forward:

This dataset has allowed me to visually connect these cultures in areas scholars had not done so before. I was able to track changes the pose underwent in Egypt, southwest Asia, and in the Aegean, but also how the Aegean’s smiting pose effectively changed the artistic canon of Pharaonic Egypt. Although compiling the dataset has been pivotal for developing my research, the question of the evolution of this pose will be further discussed in the dissertation. Once the data gathered is in the proper format, it will be uploaded to a shared open-access site such as Zenodo or Harvard Dataverse.

These sites will allow the data to be accessible to all who wish to recreate my work and provide a DOI to be cited when necessary. As this is one part of my dissertation’s digital component, the next step will be to create a map. This semester, I have tried out Mapbox to see if that program would best suit my needs. I also know how to create maps using ArcGIS. The downside to this is that there will be many objects of material culture left out due to unknown provenance, hence the benefit of creating the timeline based on style dates to include a more in-depth comparanda.

Trial creating Heat Map detailing find spots of artifacts with smiting pose using MapBox.

A portion of this project has been submitted as a poster presentation for the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) annual meeting as well as for the American Society for Overseas Research (ASOR). If accepted, a smaller timeline will be used and accessible to viewers via a QR code. Though only a selection of this data will be presented at the conference, the entire dataset will be available to scholars if they so wish to view it. A new timeline will be created using one of the free timeline codes from the CSS timeline to fit the viewers’ needs best as they will be viewing it on their mobile devices.

Thinking about how the viewer will consider the product and interact with it needs to be addressed, especially since the phone screen creates a very different visual compared to a desktop screen. Even if a portion of the timeline for the poster could be in print, I would again need to change my viewpoint to recreate the narrative best.

This project marks the beginning stages of my dissertation research and I am very excited to see where it takes me. For further updates and information about this project, please see www.bronzeagesmitingpose.com in the future or email Tenninger Kellenbarger at tug62578@temple.edu.

References

Bestock, L. 2017. Violence and Power in Ancient Egypt: Image and Ideology before the New Kingdom. Routledge.

Papadopoulos, A. 2006. “The Iconography of Warfare in the Bronze Age Aegean.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Liverpool.