By Elizabeth White Vidarte

Introduction: Tracing the Roots of Modern Psychiatric Care

Tracing the roots of modern psychiatric care turns out to be far more complicated than traditional accounts of medical progress typically suggest. This is in part because the status and origin of mental illness and disability — mind problem or brain disease? — remains nebulous to this day, even as our understanding of the fundamentally intertwined nature of bodies and minds improves. More than for other kinds of illness, the meaning of the latin origins of the word “cure” — curare, to attend to — is especially relevant to understanding approaches to mental illness because the questions of how to “cure” or eliminate disease and how to “care for” or manage it were often inseparable.

Dominant understandings of effective psychiatric care as largely behavioral or instead bodily have repeatedly shifted, pendulum-like, over the last two centuries. Physicians advocated ‘cures’ that swung from the “moral treatment” of the late 18th C that emphasized supervised behavioral recuperation to the late 19th C focus on electricity and magnetism to physically strengthen “weak” nerves.

The story of psychiatric medicine, then, is one that centers around how to define care. Alongside changing definitions of care arose the question of who was best prepared to provide such care. The professionalization of American nursing after the civil war accelerated rapidly at the end of the 19th C largely because exploding populations of the institutionalized mentally ill required better qualified nursing staff to replace the attendants — often former patients — of early asylum days.

Text Mining HathiTrust’s Digital Archives of Mental Health Textbooks

One way to trace changes in the care of the mentally ill is to track the kind of knowledge that was expected of psychiatric nurses as their professionalization efforts gained steam. To do this, I collected and prepared two sets of care manuals and textbooks pulled from HathiTrust’s digital collection by searching the key terms “mental health” and “manual or textbook or nursing.” The first set contained six manuals published between 1886 and 1899, while the second set contained 14 texts published between 1904 and 1921. The increase in number correlates to the increase in nursing schools and the number of psychiatric nurses. The second set also contained a wider range of subjects as mental health nurses were expected to widen their knowledge base from the purely practical to more fundamental physiological information about the human body.

While some trends were visible even from a cursory examination of the titles in each set — for example, the changing status of care workers from attendants to nurses is indicated in the change in title of William Granger’s 1886 “How to Care for the Insane; a manual for attendants in insane asylums” in its second edition in 1891, “How to Care for the Insane; a manual for nurses” — comparing the sets using word frequency counts offered other insights.

I used HathiTrust’s Research Center’s algorithm for ease of use and automatic text cleaning to create token counts for each set. I could then compare the relative word frequency rates in each set, to see that while the most frequent word remained the same in both sets — “patient or patients” — the relative frequency dropped from 2.63% to 1.05%, suggesting that the emphasis on patients was being diluted by the increased general medical knowledge expected of nurses as schools standardized their curricula.

Recognizing Patterns in Word Frequencies in Psychiatry

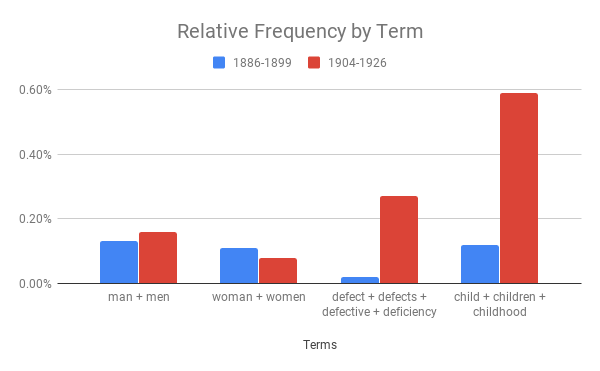

Even more interesting were the patterns that emerged for terms related to gender cues and the medical professionalization of psychiatric care. For example, the second most frequent word in the second set was “child/childhood/children,” suggesting an increased interest in heredity that matched an increased frequency in the term “mental defective.”

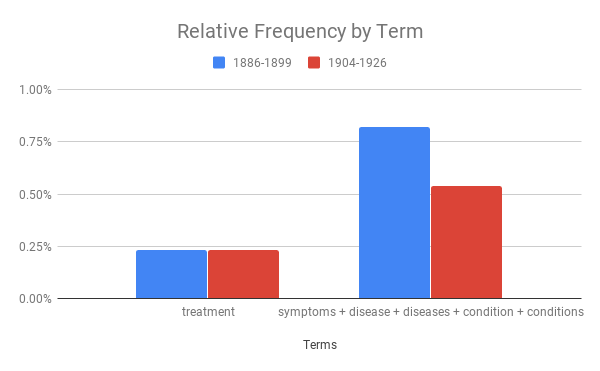

Another interesting note is that while the relative frequency of words connoting disease went down in the second set of care manuals from 0.82% to 0.54%, the relative frequency of the term “treatment” remained the same. This suggests an increasing interest in sociological rather than bodily interventions as “treatment” for mental illness and disability; the emphasis was on “what to do” and “where to put” the mentally ill and disabled as institutions overfilled, rather than on the body as the site of medical cure.

Conclusions: What Next?

This project set out to understand how nursing care reflected wider medical understandings of mental illness/disability and its treatment. I focused on the language choices these nursing manuals and textbooks made to describe, label, and discuss mental health — their rhetorics of care. Comparing the two sets of care manuals revealed changes — such as the drastic drop in references to “attendants” and “asylums” and increase in the term “defective”— which reflect the professionalization of nursing and its curriculum but also the changing nature of mental health care. Institutions were less likely to be considered “asylums” from the turbulent world. Rather, they took on explicitly custodial functions to keep the “mental defectives” away from society.

An expansion of this pilot requires seeking out a wider range of texts to examine, including nursing memoirs recounting the experiences of so-called “asylum keepers” and asylum nurses. Further comparisons between the experiences of nurses and other important actors — such as patients and psychiatrists versus psychologists — and differentiating between the experiences of hegemonic group members and those who were already widely oppressed — such as black men and women, poor white women, and immigrants — would bring further nuance to this project. Based on my results so far, a focus on relative word frequencies within genres promises to reveal the intricacies of the rhetorics of care in medicine and its wider social context.