By Hocheol Yang.

As a doctoral student and lab manager of M.I.N.D. Lab in School of Media and Communication at Temple University, I have been studying and interested in how people interact with media, as well as human and computer interactions. This summer, I have a great opportunity to study how we can explore virtual reality with the Oculus Rift at Digital Scholarship Center (DSC). I am glad that I can introduce the future of media in our lives. I would like to start this summer project by introducing virtual reality and augmented reality, because they are the essential definitions needed to discuss humanism issues in such a different type of media.

I Virtual and augmented reality

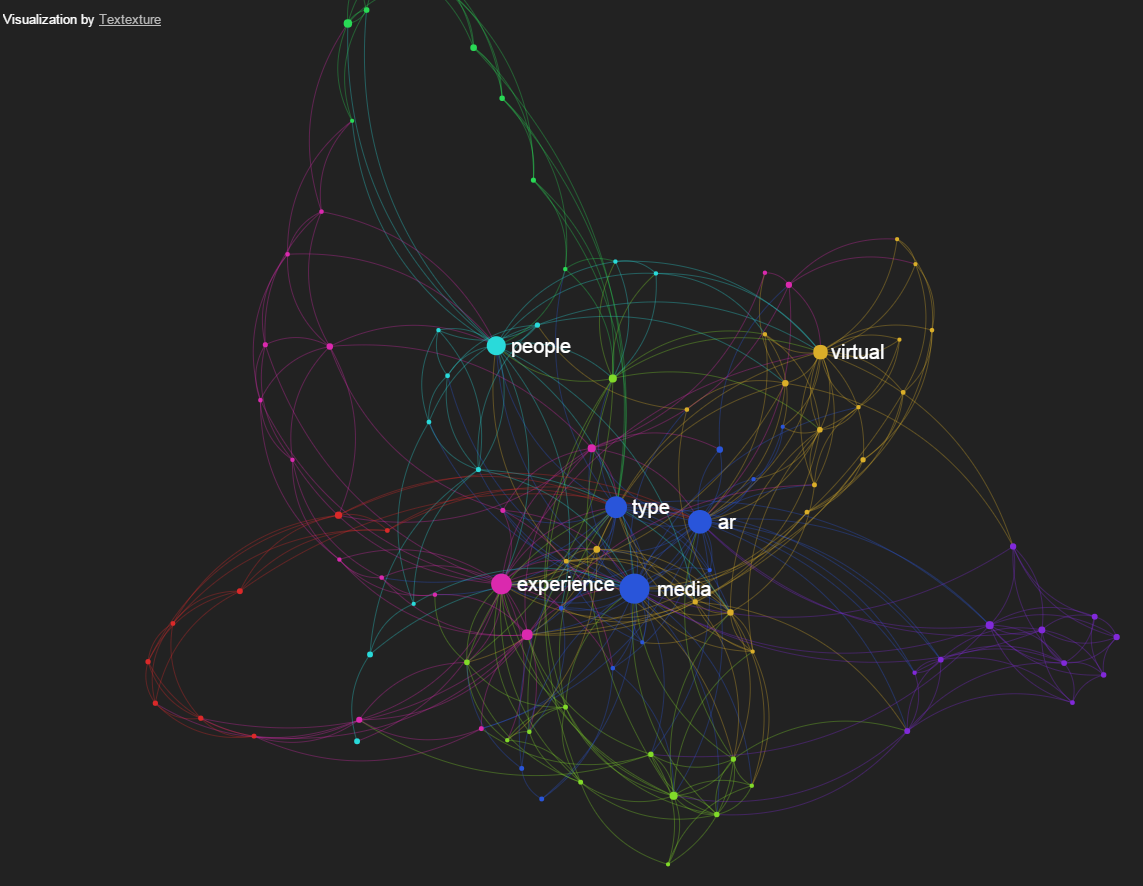

There are different terms that explain certain behaviors and experiences in our daily lives. We describe these experiences not only with fancy new terms like having Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) experiences, but also with familiar terms like reading books, watching movies, seeing pictures and paintings, and listening music. All of these appreciative activities tend to be experiential rather than informational, and content of them are mediated textual artifacts or constructs among humans rather than real experiences. Although it looks like we do these activities regularly, there is no commonly agreed term to describe the nature of these human activities.

For example, I wonder if you have been to Tokyo. Even if you have no chance to stay in such a far away city, you might already have some sense how the city looks. Books, television shows, movies, and news stories already help us to structure how the foreign city looks in our mind. Even if all of these different textual artifacts among help us to construct a single sense about Tokyo, the ways they present the city are different each other. Although all of these experiences are limited, because they are partial experiences, these experiences complement each other in order to construct more complete sets of representations about Tokyo. In our mind, VR and AR provide some additional dimensions to the city with more vivid and interactive experiences.

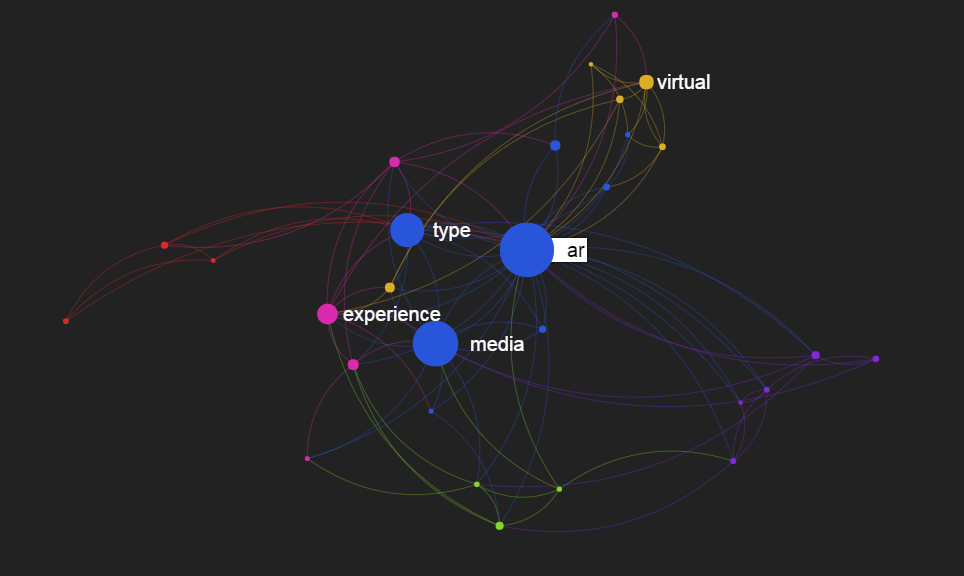

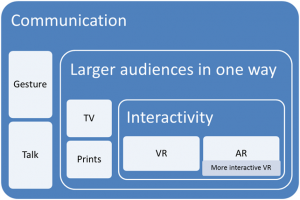

In fact, books, pictures, televisions, web pages, VR, and AR are just different types of media that transmit humans’ creative artifacts to other humans. Although each of these different types of media has its own uniqueness and we use different verbs to describe what people do with this media, what we essentially do with this media is the same. In other words, we can say that people do the same activity but their experiences are totally different. Therefore, it is embarrassing to watch debates about benefits and disadvantages between reading books and watching television, because what we experience between two different types of media are totally different and we can hardly compare. Even if these types of media have their own uniqueness, there are some patterns that separate VR and AR from other types of media.

I Virtual reality

VR was first introduced at 1989 by Jarron Lanier, but the definition of it was unclear until 1992, as Steuer, Biocca, and Levy explained at 1995. VR is similar to other types of media in that it delivers human created experiences, but according to the paper of Steuer, Biocca, and Levy, VR is the only media that provide interactive experiences. For example, if you just watch a movie with Oculus Rift, then it is hard to say that the experience is VR, but if the views or images of the movie are changed by any type of your act, then this interactive feature differentiates the experiences as a VR. For example, televisions are not considered VR in general, but one of the recent trends is the second screen viewing, where people can express their responses to live programs and where their responses have influences on the programs’ future directions, such as votes on American Idol. In this case, we can say that these types of TV shows are also considered VR, though some people may believe that whether the settings of these shows are virtual and artificial or real is arguable. I would bet that reality shows like this type can be considered VR that are presented by real individuals because they behave in an artificial setting.

I Augmented reality

How about AR? According to Azuma’s paper on 1997, AR is a different type of VR. AR allows VR users to see the physical world where they stay. Allowing users to see through VR displays is one of the ways to increase seamless interactivity. Head Mounted Displays (HMD), like Oculus Rift, also increase interactivity in a different way than AR does by presenting more immersive and interactive views with head tracking. Therefore, there are attempts to make devices such as see through HMDs, and tactile feedback, and motion tracking add-ons. These technologies are all the efforts to increase seamless interactivity. Therefore, AR is one of the types of VR that enhances interactivity between users’ physical location and virtually created information. There are some examples this trend below.

Photo: Motion and mass simulated training equipment on Virtual Reality Laboratory of NASA by NASA

Photo: Norwegian army using AR to acquire better visuals around their armored vehicle by IEEE Spectrum

Photo: Remote AR to see through in remote work places by WSJ

It might be odd to see that “virtual-ity” or “virtual-ness” is somewhat irrelevant to define VR. That is why some scholars like me sometimes prefer to use the term interactive media than VR, as Markus pointed out on 1987. Discussions about distinguishing real and virtual are a fascinating and humanistic question, but it is hard to find a clear answer, Lombard, and Ditton’s paper on 1997 explains that this is because these questions about distinguishing real and virtual tend to end up as discussions about who we are and what a human is, and where we are present and feel presence in a certain place.