By James Kopaczewski

As introduced in Alex Wermer-Colan’s latest blog, the Digital Scholarship Center in collaboration with Temple University Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center and Digital Library Initiatives has been digitizing a corpus of New Wave science fiction novels. This project seeks, in part, to assess the mass market production of science fiction novels in the 1960s and 1970s.

After digitizing a set of literary classics, especially of the New Wave era, Alex, Crystal, and I have focused on sorting a second batch of novels for digitization. We found that alternate history narratives represent a small but vibrant segment of The Paskow Science Fiction Collection. Our curated list of alternate histories for digitization include:

Gregory Benford and Martin Harry Greenberg, Hitler Victorious (1986)

Harlan Ellison, I Have No Mouth & I Must Scream (1967)

Harry Harrison, A Rebel in Time: The South will Rise… (1983)

Jake Saunders and Harold Waldrop, The Texas-Israeli War: 1999 (1974)

Joanna Russ, The Female Man (1975)

Martin Cruz Smith, The Indians Won (1970)

Michael Moorcock, Behold the Man (1969)

Norman Spinrad, The Iron Dream (1972)

Philip K. Dick, Clans of the Alphane Moon (1964)

Philip K. Dick, Time Out of Joint (1959)

Philip K. Dick, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (1982)

Philip K. Dick, Valis (1981)

Robert Harris, Fatherland (1992)

Robert Moore Williams, The Day they H-Bombed Los Angeles (1961)

Roger Zelazny, Roadmarks (1979)

Wilson Tucker, The Lincoln Hunters (1958)

Recently, alternate history narratives have transitioned from an obscure sub-genre to a staple of contemporary popular culture. From Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Underground Railroad (2016) to Netflix’s adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962), alternate history has taken a prominent place in American media. In fact, the alternate history moment seems here to stay for the foreseeable future. Last July, David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, the co-creators of the television version of Game of Thrones, announced a post-GOT project entitled, Confederate. Set in a dystopian, independent Confederacy where the Mason-Dixon Line serves as a demilitarized zone, Confederate takes place at the brink of another Civil War. Despite considerable criticism for its facile presentation of slavery, Confederate remains in development. Similarly, Amazon has been developing Black America a series set in a post-Reconstruction world where Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana were granted to African Americans as reparations for slavery.

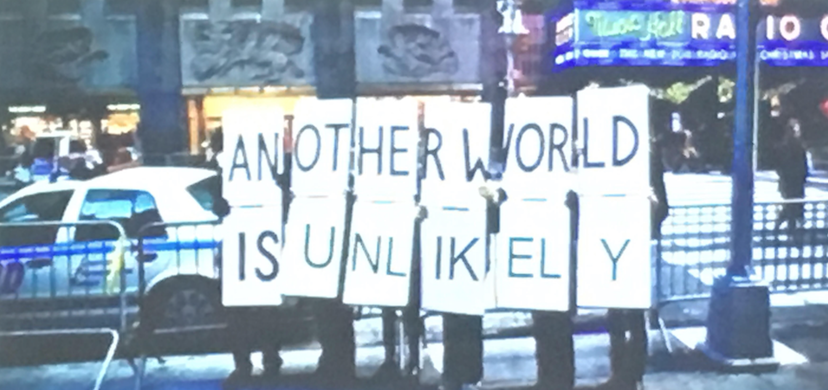

The popularity of alternate history narratives has even extended to contemporary American politics. Writers have employed alternate history as a means of unraveling the meaning of the election of 2016. Despite their contemporary relevance, alternate history narratives follow a longer historical trend. Upswings in the production of alternate history narratives commonly follow significant historical events. For instance, the horror of the Second World War was a critical juncture for the development of alternate history narratives. A string of novels, such as The Man in the High Castle (1962), Hitler Victorious (1986), and Fatherland (1992), were released in the aftermath of the war and describe a world ruled by triumphant Nazis.

The Cold War also became an important vehicle through which writers rewrote the possibilities of world history. Many New Wave science fiction novels grapple with issues inherent to the global struggle between the United States and Soviet Union, particularly rapid modernization, economic competition, and imperialism. Fear of arms proliferation and nuclear holocaust colored novels, such as The Day they H-Bombed Los Angeles (1961), which discuss the destructive capability of atomic weapons.

Yet alternate history narratives have not always been dark depictions of mankind at its worst. Alternate history often focuses on the redemptive capabilities of humans. The Lincoln Hunters (1958) follows time travelers who search for Abraham Lincoln’s “Lost Speech.” The “Lost Speech,” a fiery critique of slavery, held the key to unsettling the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow. Martin Cruz Smith’s The Indians Won (1970) explores a world where Crazy Horse survived assassination and unites Native American societies against the United States. Crazy Horse defeats the United States Army and defends native sovereignty by developing nuclear weapons. Whether redemption comes through a lost speech or Native American independence, many alternate histories create more pleasant worlds.

While most historians view alternate history as either irresponsible or irrelevant, literary scholars have begun to unpack the complexity of the sub-genre. Michael Butter, Jerome De Groot, Amy Ransom, Kathleen Singles, and Giampaolo Spedo have treated alternate history narratives as a serious field of inquiry. Literary critics have also assessed the merits of alternate history. Thomas Mallon, a critic for The New Yorker, notes that alternate history allows writers to “retouch destiny.”

In an era of political and environmental turmoil, alternate history narratives will likely remain an avenue in which writers explore our hopes and fears. As we conclude the digitization process, we hope to include additional alternate history narratives into the corpus. If you know any novels that have not been included in our list, we would like to hear from you. Check this space for future posts on mapping alternate history narratives and how computational text analysis can be used to examine the ways science fiction writers reimagined history.

“Evil (ignorance) is like a shadow—it has no real substance of its own, it is simply a lack of light. You cannot cause a shadow to disappear by trying to fight it, stamp on it,