By Emily Logan

What is Citizen Science?

Do-it-yourself science, also known as punk science or citizen science experiments conducted by amateur public experimenters are cropping up all over the world. These grassroots projects are intervening and producing results that are filling in gaps in environmental data that many governments are ignoring. Alan Irwin, a British sociologist, coined the term “citizen science” and defined it as “developing concepts of scientific citizenship which foregrounds the necessity of opening up science and science policy processes to the public”(1). In Irwin’s mind, as well as many others:

- science should be responsive to the concerns and needs of local communities

- citizens themselves could produce reliable scientific knowledge

How Can Citizen Science Provide Agency Around Climate Change?

12/19/2017

The image above is of Max Liboiron testing out one of her latest experiments. She is a feminist scientist who has devoted her research to solving issues related to waste, plastic pollution and anti-colonial science. “Baby Legs”, the name of the experiment, is a DIY kit being used by concerned citizens in Newfoundland, Canada who are seeking to monitor the soil, water and air. It is a replacement to the Manta Trawls, a device costing around $3,500, with which scientists skim the oceans for microplastics. Liboiron’s device is made of synthetic baby stockings and half a plastic bottle. The cost is only a few dollars and the instructions to build the kit are on Liboiron’s Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR). Projects like this that provide agency to citizens are made possible through crowdsourcing, open data sharing and simple tutorial kits.

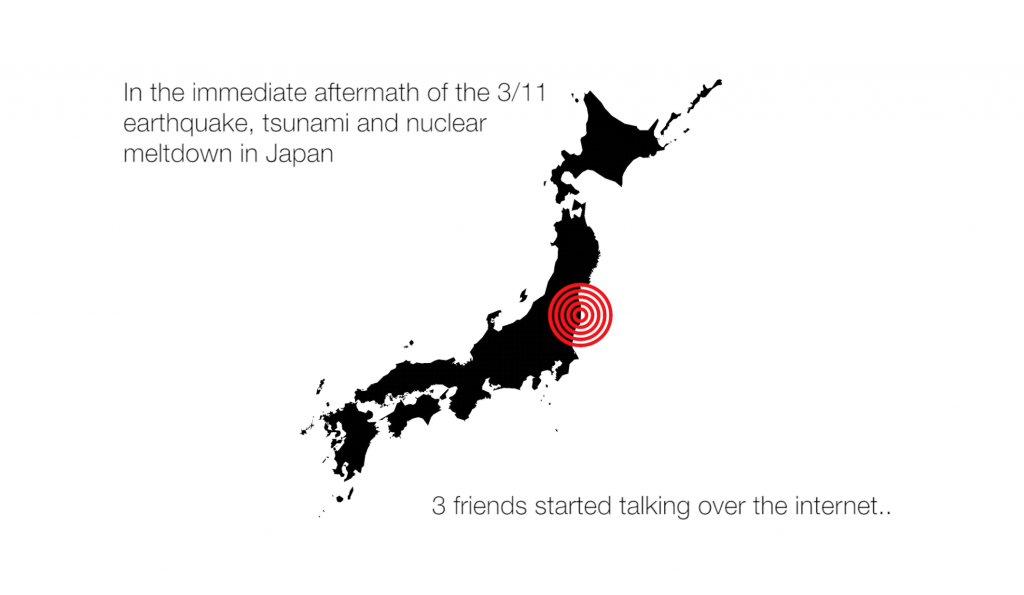

Another example of a citizen science project is Safecast. After the disastrous earthquake that took place in Fukushima, Japan in 2011, several scientists began talking on the internet about solutions to the catastrophic problems the communities were facing. The government was not transparent about radiation levels and was not actively responsive to the pressing concerns. In addition, there was no street by street data on the radiation levels around the nuclear power plant calamity. Joi Ito, along with a few other scientists launched Safecast and built a DIY bGeigie Nano which is a mobile, GPS enabled, logging radiation sensor. The device is designed to be mounted on the outside of a car, bike, train, plane or other mode of transportation. The device tracks static readings and contamination findings and logs the location and time coordinates. They recruited citizens to collect data and ended up gathering over 40 million datasets. Collecting and disseminating transparent, unbiased data on environmental conditions puts the power and know-how back into the hands of the people effected most by the problem. It can provide citizens with the leverage to pressure governments to respond, change policies and provide resources to fix large scale problems.

“What Safecast proves is that all the preparation in the world – all the money in the world – still fails if you don’t have a rapid, agile, resilient system”.

– Joi Ito

Why Does Citizen Science Matter to the Digital Humanities Field?

The sciences and the humanities actually share a lot of the same issues, and questions. Both fields involve a host of socio-technical issues where solutions are influenced by social, political and historical factors. Often the data may appear different, but, regardless, “21st century skills include “critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, effective communication, motivation, persistence and learning to learn”.

“Consider how matters of climate change involve human perception, bias, and communication problems, along with the material and technical realities of climate”(2).

What might more citizen science projects on climate research look like?

A Few Project Platforms for Citizen Science

Resources and Citations

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology (intellectual property and project design) – ethics and project design of citizen science

- European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) Ten Principles of Citizen Science

- Citizen Science Project Finder

- Adafruit Blog – Citizen Science Topics

(1) H. Riesch; C. Potter (2014). “Citizen science as seen by scientists: Methodological, epistemological and ethical dimensions”. Public Understanding of Science. pp. 107–120. doi:10.1177/0963662513497324.

(2) Mehlenbacher, Brad, and Ashley Rose Mehlenbacher. “Finding the Common Culture: Uniting Science and the Humanities in Citizen Science.” CitizenSci, 18 July 2017, blogs.plos.org/citizensci/2017/07/18/finding-the-common-culture-uniting-science-and-the-humanities-in-citizen-science/.