By Michael Glass

The digital humanities do not have a central place in philosophy, and so much of my work starting out has been learning the tools of stylometric analysis and also trying to see what has been done with those tools. Stylometry is the use of statistical tools (such as on word frequency) to measure the style of a work and compare it with the style of other works. As I have been teaching myself, I have had exposure to some of the primary literature (such as the paper in which Burrows proposed his ‘Delta’ procedure, an important tool). But what I have found most interesting so far are the debates surrounding the use of stylometric analysis in philosophy.

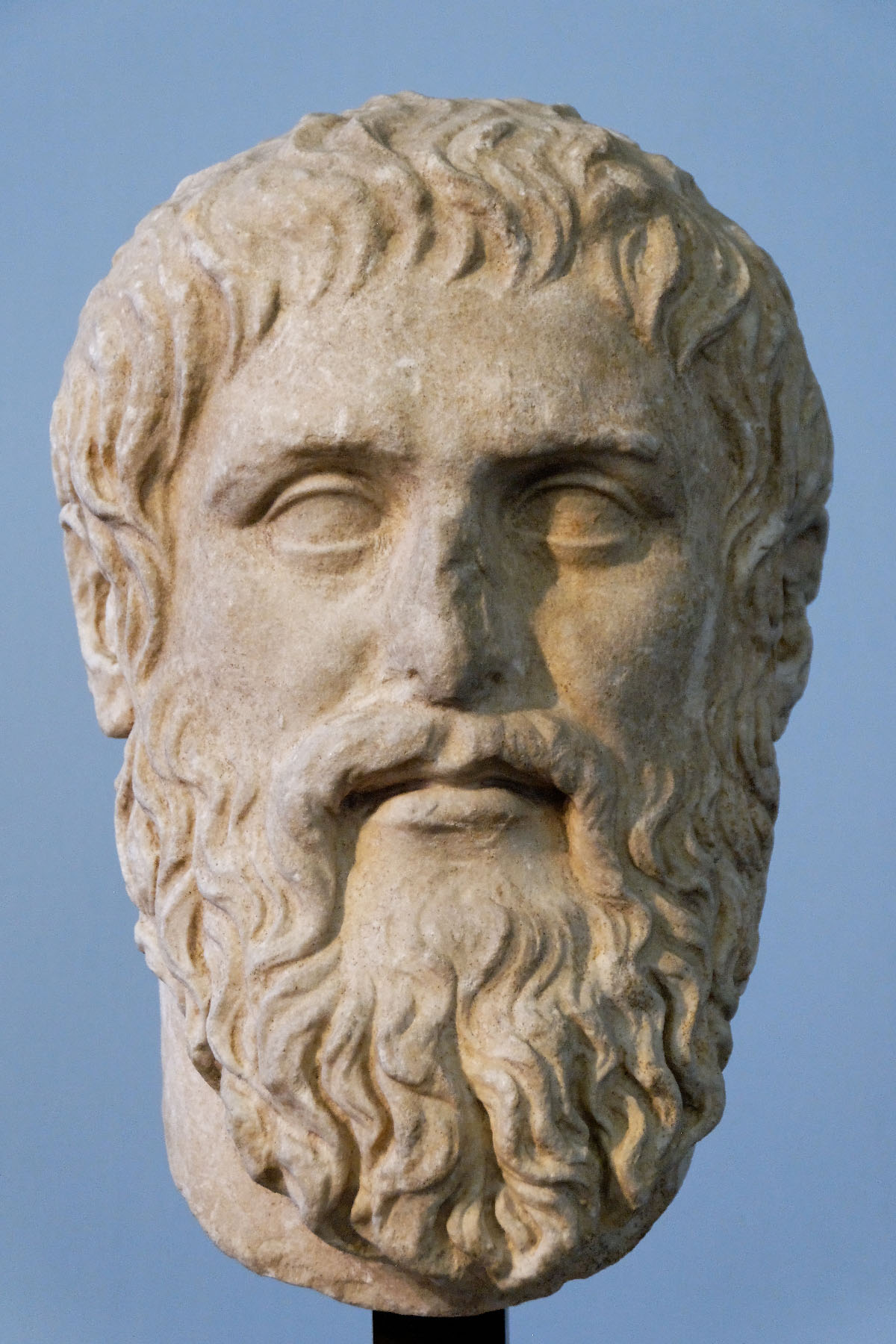

Where stylometry has seen its greatest use thus far is in Plato scholarship, where it has been used in an attempt to determine the order of Plato’s works. For a large part of the twentieth century, a dominant theory was that Plato’s works could be interpreted as belonging to an early, middle, and late period. The idea is that each of these periods could be understood as distinct phases which should be interpreted together. But then it would matter what order Plato’s works were written in. Much disagreement centered on the Timaeus.

The debate over the Timaeus was viewed by G.E.L. Owen (1953) as determining whether Plato still held to his metaphysics in the late period. Owen interpreted Plato as abandoning his metaphysical views (due to an argument in the Protagoras), but the Timaeus retains them. Therefore, Owen thought, the Timaeus must be before the Protagoras, and must be a work of Plato’s middle period. This flew in the face of common wisdom at the time, as stylometrists agreed that the Timaeus was one of Plato’s latest works. Owen declared them wrong, and argued that the philosophical arguments should take precedence over the stylometric work.

Against Owens, H.F. Cherniss (1957) defended the stylometrists, saying that Owen’s criticisms were baseless. Further, Cherniss attempted to show problems with Owen’s philosophical arguments, saying that Owen had missed the details of Plato’s arguments, and that Plato maintained his metaphysical views up to the end of his life. Owen, Cherniss argued, wanted Plato’s views to look like his own, and misinterpreted Plato on that basis.

What both Owen and Cherniss left alone is the assumption that Plato’s views followed the development thesis. Could Plato’s views be so readily cleaved into three portions? Without an answer to this, it is not clear that stylometry would have been so enlightening. Whether or not there are philosophical uses for stylometry, it is clear that, if there are, there have to be philosophical assumptions which allow this. And these assumptions cannot be backed up by stylometry, they must be backed up by philosophy.

Sources:

Cherniss, Harold. “The Relation of the Timaeus to Plato’s Later Dialogues.” The American Journal of Philology 78.3 (1957): 225-66. Web.

Owen, G. E. L. “The Place of the Timaeus in Plato’s Dialogues.” The Classical Quarterly 3.1/2 (1953): 79-95. Web.