By Sreedhar Nemmani

In my first Scholars Studio Blog Post, I discussed my project, Cartographies of Communication, which investigates the genealogies of the concept of communication. The project aims to locate key actors who shaped the field of communication by tracing the scholarly influences that molded our understanding over time of what communication means and is. My project traces the complex network of communication scholarship and situates it within specific geographical locations. I hoped to use visualization tools like network analysis and timelines in this project.

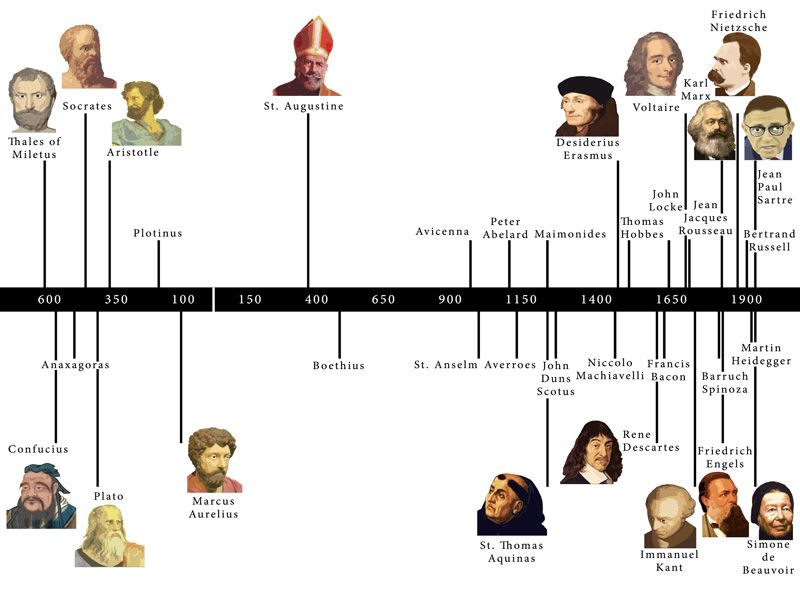

At LCDSS, I engaged with several scholars, from ancient Greek philosophers to British, French, and German Enlightenment philosophers to modern communication scholars, especially in the founding years of the field of communication studies, the first half of the twentieth century. During this research, I found that tracing the genealogies of communication can become tricky, especially when we look at the scholarship retrospectively. Here, any attempt at tracing genealogies is laced with the possibility of ascribing influences where there may be none. In this blog post, accompany me as I iterate these problems and discuss a creative way of circumventing this gargantuan knot.

Tracing Genealogies as a Function of Power

Investigating the origins of communication, I found that tracing genealogies is an act of power: It has the power to establish connections, thus empowering certain master narratives (Lyotard, 1984) while relegating others to the proverbial backburner, if not a dustbin. For example, let us trace the earliest formulation of communication.

Humans have communicated for as long as they have existed. However, the vocation of thinking about human communication as a distinct entity emerged during the European Enlightenment period, imbibing investigation into human communication with a salient feature inherent within the modern scholarship: tracing the origins of human knowledge to Greek philosophers. For example, though Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke (identified as one of the earliest theorists of modern communication) do not directly quote Aristotle, Whitney J Oates (1948) traces the ancient origins of communication to two of Aristotle’s extant works, Georgias and Phaedrus. Such tracing is, however, not natural or neutral.

Outlining the origins of modern philology, Peter K.J. Park (2013) points out that though there was a long European tradition of accounting philosophical influences from across the world, by the late eighteenth century, the (European) historians of philosophy began to claim ancient Greece to be the cradle of all human knowledge. Such claims fed into and bolstered the then-colonial needs of manufacturing a ‘mythology’ of European supremacy (Kies, 1953). These manufactured mythologies continue into modern scholarship where we maintain a continuity of knowledge generation from classical Greece to modern times. This continuity, however, is often recreated, for the connections between Greek antiquity and Enlightenment-era Europe were severed during the ‘dark’ Middle Ages. These connections were reestablished only during the latter period; Oates’s work is an example. In retrospect, such redrawing of connection(s) poses a peculiar problem in tracing intellectual genealogies.

From Linear to Non-Linear Timelines

Corresponding to the apparent linear progression of time, genealogies are often imagined as linear family trees tracing generations from one origin point. This ingrained perception of linearity captures our very imagination when drawing intellectual genealogies, particularly through timelines, as such inherits claims of a perceived continuity of human knowledge from a European source, mostly from Greece, and branches out into a multitude.

This fails to account for the nature of knowledge-generation practices. The craft of conducting research and generating knowledge involves actively searching, a form of scholarly shopping, to identify the most pertinent and extant scholarship that could help us explain the phenomenon we investigate. Let us call the drawing of such timelines as generating ‘Retrospective Genealogies’ assembled block-by-block.

Network analysis is another way of tracing the complex connections, interactions, and influences amongst scholars. While this method of visualization does help us establish the connections between different scholars, thus breaking out of linear progressions, network analysis does not provide contexts as to why someone was citing or quoting someone. It also does not give much information about the spatial or temporal contexts.

So, using network analysis or timelines might not be quite useful in understanding the history of an idea, for the influences are not linear but are almost like interlinked spirals, with each generation of scholars searching for and finding theoretical and methodological justifications for their work.

Digital Storytelling for Tracing Genealogies

It is one thing to say that linear genealogies are drawn retrospectively, but another to ask how we can proceed. One model that comes to our rescue is the power of storytelling. Unlike a biological family tree, scholarly lineages are often forged and reforged, akin to the evolution of stories, mythologies, or even social norms that are told and retold from one generation to another. In that sense, genealogies, too, acquire the nature of scholarly storytelling where traditions are forged and reforged.

However, such genealogical stories are contextual and have specific spatial and temporal imprints. For example, the desire to connect modern academic knowledge generation with the classical ages of Greek and Roman civilizations emerges from the specific spatial and temporal contexts of the Western colonial conquests. Similarly, the emergence of academic traditions in modern times is also linked with specific spatial and temporal contexts, like the emergence of various schools and institutions of higher education in Europe and North America during the pre- and post-World War periods and postcolonial eras. In other words, genealogical influences are always rooted in specific geographical and cultural contexts.

Bringing these two aspects together, I was elated that LCDSS introduced me to Scrollytelling —a way of telling a story while also situating the story in specific geographies, thus giving me an avenue to visualize non-linear genealogies. Using open-source Maplibre repositories in GitHub, I have started building a webpage that shares the story of the evolution of the field of communication while also locating this evolution on a map. Using these repositories requires some basic knowledge of Javascript language, and I have also been brushing up on my basic coding skills. I am grateful for my time at LCDSS. It was filled with intense debates and explorations of various digital visualization tools, their strengths and drawbacks, and their suitability for specific purposes.