By Jessica Braum

In recent years, digital humanities tools have opened new avenues for research across various fields, enabling the visualization of complex data in ways previously unattainable. My ongoing project, which examines Kim Lim’s artistic practice through the framework of global modernism, employs ArcGIS Story Maps to explore the geographical, cultural, and historical contexts that shaped her artistic career.

The study of Lim’s cosmopolitan artistic practice may be augmented by using digital maps to produce tangible documents of her transversal movements through Asia and Europe, revealing the nuances of cross-cultural encounters embedded in global and geopolitical interchange. During my Graduate Externship, I will explore methods for mapping Lim’s biography, artistic practice, and influences to shed light on how broader art historical narratives collide with the dynamics of globalization.

Contextualizing Kim Lim’s Artistic Practice

Kim Lim (1936–1997) was a printmaker and sculptor of Asian descent who worked primarily in London. While Lim is often described as British-Singaporean, this geographically and nationally bound identification overlooks the multiple and variable sites of belonging necessary to understand her place of birth, cultural affinities, perspective, and artistic practice.

Born in a British colony that would later become the Republic of Singapore in 1965, Lim grew up in Singapore, Malacca, and Penang. Her father, a magistrate for the British government, was posted to various locations across Southeast Asia, moving her family accordingly. During their time in Penang, Lim’s childhood coincided with World War II, including the Japanese invasion and occupation of the region. She later recalled adopting elements of Japanese culture simply because it was “all around.”1 After the war, Lim’s family returned to Singapore, where she attended the Methodist Girls’ School. There, classes were taught by American missionaries while adhering to the British Cambridge Exam curriculum. Lim remained in Singapore until 1954.

At the age of 18, Lim moved to London, where she studied under Anthony Caro at St. Martin’s School of Art. She later transferred to the Slade School of Fine Art, where she pursued sculpture and printmaking from 1956 to 1960. From her student years, Lim’s interest in abstract sculpture converged with the emergent trends of abstraction and minimalism. Although she participated in some early 1960s exhibitions highlighting a new generation of British sculpture, Lim did not receive the same recognition as her white male contemporaries. These artists, often referred to as The New Generation or The School of Caro, advanced ethnonationalist interpretations of British post-war art that excluded Lim’s contributions to the new sculptural vocabulary.

This exclusion exemplifies a broader pattern of omissions that have marginalized Lim in institutional histories of post-war art. Her absence has been attributed to narrow canonical interpretations of abstract art that disregard global influences, the nascent cultural infrastructure in Singapore after its independence, cultural and institutional sexism, her marriage to William Turnbull (an established and dominant figure in the British art world), and the political and social hostility toward migrants from former British colonies. These factors collectively underwrote the marginalization of diasporic artists within the mainstream art establishment in England.23

Mapping Kim Lim’s Cosmopolitan Subjectivity

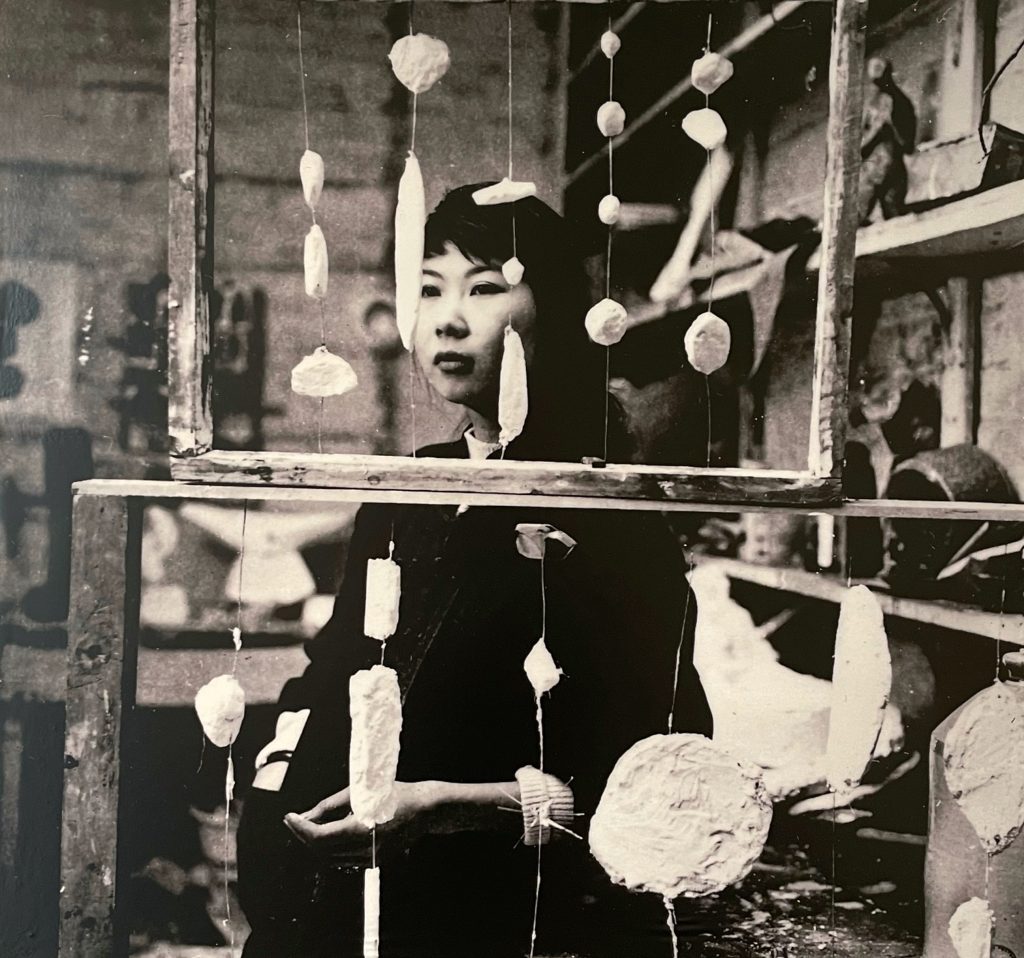

Lim traveled between Singapore and England throughout her life, regularly stopping in Greece, India, Japan, China, and other intermediary locations to visit art museums, ancient architectural sites, and monuments. Her artistic practice was informed by these travels, as evidenced by the diverse visual references collaged across the pinboard in her studio. Cumulatively, these encounters contribute to the constellation of influences shaping Lim’s cosmopolitan imagination, born from her geographic and cross-cultural movement.

During Lim’s lifetime, the official criteria for defining “British art” often excluded the sociological, cultural, and topographical intricacies of complex movements, relegating non-white or “foreign” artists to the margins.4 Consequently, it is necessary to re-historicize Lim as a cosmopolitan artist whose nuanced practice challenges the structurally problematic binaries of East and West. Traditionally, art history has relied on texts, archival research, and visual analysis to contextualize artists and their work. However, developments in the digital humanities have expanded the methodological toolkit available to art historians. Digital story maps, for instance, enable the plotting of sites of engagement, revealing connections between geographic locations, artistic movements, and cultural influences.

In Kim Lim’s case, the need for such a tool is particularly pressing: her formative biography reflects the profound geopolitical shifts in Southeast Asia and the United Kingdom during the twentieth century. Moreover, her plurilocal subjectivity encompasses both a transnational practice and a cosmopolitan imagination.

Methods for Mapping Transnational Art Histories

ArcGIS Story Maps allow for the visual presentation of geographic data alongside narrative text, images, and multimedia. This visualization provides a contextual perspective on the information presented. In developing my approach, I consulted various art historical mapping projects, including Patricia Belen’s “Mapping Artist Nationalities at MoMA” (2020), which plotted the nationalities of artists in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, and Katelyn Wattendorf’s “The World of Abby Weed Grey: Creating a Collection” (2021), which visualizes the travels and acquisitions of art collector Abby Weed Grey.

My project involves using ArcGIS Story Maps to chart the geographic points significant to Kim Lim’s biography and artistic practice. These points include locations where Lim lived and worked, as well as places she visited that influenced her art, such as Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the ancient Cycladic sculptures she encountered in Greece, and the Taklamakan Desert in Dunhuang, China.

As a diasporic artist, Lim’s transnational encounters produced a collection of visual references that she meaningfully distilled into her artworks. To map the positions—both geographic and perspectival—from which Lim experienced the world, I have identified the following categories: Artworks, Biography, Travel, Exhibitions, and Relevant Geopolitical Events.

By mapping these locations, I aim to create a visual narrative illustrating how Lim’s work was shaped by her transnational experiences. Her prints and sculptures engage in a dialogue with her sources of inspiration, reflecting insights she gleaned from early exposure to various cultures and later from visiting sites of cultural significance during her travels.

For example, Lim created two known artworks titled Shogun: a sculpture in 1961 and a lithograph in 1962. Shogun, meaning “general who quells barbarians,” was adopted in the 12th century to denote Japan’s dominant warlord, who wielded both political and military power. The Story Map will illustrate Lim’s encounters with Japanese culture, both as a resident of Japanese-occupied Penang during World War II and later through her visits to Zen gardens in Japan.

This type of visualization will allow viewers to see the connections between Lim’s geographic and cultural influences and the artworks they inspired, offering a more nuanced understanding of how Lim’s artistic practice was shaped by her global perspective. My goal is to create a Story Map that provides rich context for understanding Lim’s work while also highlighting the broader cultural and political forces that shaped her artistic practice.

Conclusion

The stakes of this project extend beyond Lim herself. At its core, this project challenges the limitations of traditional art historical narratives, particularly those that have marginalized artists like Kim Lim. By using digital mapping, I seek to offer a more comprehensive understanding of her work and a deeper insight into the political, social, and cultural contexts in which Lim created art.

My goal is to produce a visual narrative that captures the complexities of Lim’s cosmopolitan identity, revealing the global and geopolitical contexts that shaped her art. By leveraging ArcGIS to map Lim’s transnational experiences and artistic influences, this project will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how Lim’s movements across and between Asia and Europe informed and shaped her creative practice and artistic oeuvre.

End Notes

- “Sounds of the British Library”, British Library’s National Life Stories, accessed 8 December 2023. https://sounds.bl.uk/Arts-literature-and-performance/Art/021M-C0466X0051XX-0006V0. ↩︎

- According to data compiled by artist Liliane Lijn, important surveys of British art staged at the ICA, Hayward Gallery, and Royal Academy from 1970 to 1975 included the work of between 0% and 12% women artists. ↩︎

- In a 1968 speech, Enoch Powell, a Conservative MP, employed divisive rhetoric that contributed to binaristic attitudes about immigration at a time when England was coming to terms with a new national reality and “set in motion a complex discourse of violence, prohibitive legislation, and xenophobia that would be inextricable from immigration for at least another decade” (Martin, Courtney J., “Rasheed Araeen, Live Art, and Radical Politics in Britain,” Getty Research Journal, no. 2 (2010): 107–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23005411). ↩︎

- Guy Brett, “Internationalism Among Artists in the 60s and 70s,” in The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-war Britain, ed. Rasheed Araeen (South Bank Centre, 1989), 111-114. ↩︎