By T.A. Spiro-Costello

Gaming as a Transitory State: Developing a Card Game about Gender Identity

Games are powerful tools for experimentation. Each choice made in a game creates a new state of play from which to make novel decisions. Some choices are comfortable for players, and go according to plan, while others are unexpected and steer the player into unfamiliar conditions. Given those conditions, the decisions players make show players who they are.

My project for the Scholar Studio this year has been to design a game. Originally, I envisioned a tabletop game for 2-6 players. The purpose of the game was to challenge players to find a match. To do so, players would need to make choices, pursuing romantic partners, and along the way improving themselves, making themselves smarter and more charming, or other things that might appeal to their chosen partner(s).

The game has two main purposes: first and foremost, it is a game about discovering gender and understanding those implications as a potentially trans person. The second is to put the players at risk for experiencing unrequited love.

Overview of Game Design

In a previous post, I described how games meld realities of lived experiences through rules in order to generate unique interactive experiences. One goal for this project was to harness game concepts in commenting on transgender experiences in some way.

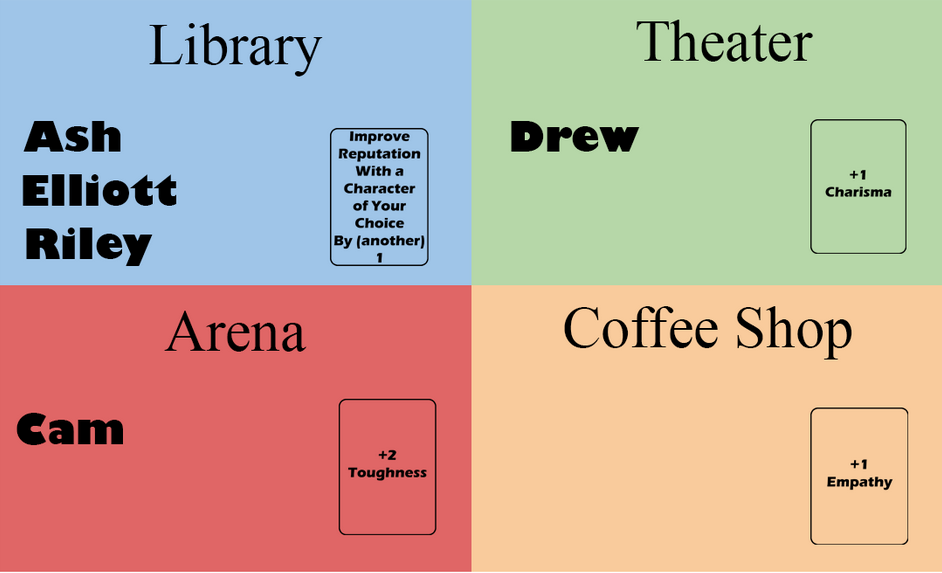

At the beginning of the game, players are dealt a card. This card is to be kept face down through the first several turns. During these turns they will go places and improve themselves–getting tougher, for example.

As they go to different locations, like the library or the arena, they increase their reputation score with the five romanceable characters in the game. These romanceable characters have personalities that determine their tendencies–where they will go and what traits appeal to them.

A few rounds in, some of these romanceable characters will reveal their sexuality to the players. Later on, players will overturn the card that has sat face down in front of them from the beginning of the game and come to terms with their in-game gender identities.

The experience of play is meant to be simple and positive. There is no gendered connection between the player and their in-game avatar. A “Man” card doesn’t specify whether the player is a man who is cis or trans. At the beginning of the game the player doesn’t know what their gender is, but once that information is revealed the player can go about the game with the confidence that they know what their gender is and what partners they’re compatible with.

The game does not address what others assumed the players’ gender was and it doesn’t matter to gameplay. Similarly, romanceable characters only have sexualities indicating which gender identities they’re attracted to without differentiating between cis, trans, nonbinary, genderfluid, etc.

Similarly, players’ actions can only improve their characters. They cannot lose progress they’ve made in their characteristics, and they cannot lose reputation with their crushes. In the end, a crush may prefer one player over another, but the improvements player characters make remain valid. The threat of unrequited love is ever-present and it’s always possible that a romance between player and crush is impossible because player gender and crush sexuality are not a match.

Gameplay then becomes a loop of going places, growing as a person because of those places, and becoming closer to people at those places. Early on, players might have a particularly good experience at one location leading to a strong relationship with a romanceable character, only to later find out that they’re not romantically compatible. Understanding these risks challenges the players to choose between appealing to the broadest range of partners or appealing to a single character that might not end up proving compatible. Managing these compatibility risks forms the crux of the gameplay decision-making process.

Conclusion

The purpose of the game is to place players in a position where they may experience a gendered identity they hadn’t thought of having, or to place them at the table with someone experiencing a gender identity they hadn’t thought of themselves as having. In presenting gender in a simplified and idealized way, gameplay can flow smoothly.

At its core, it’s a game about what we can control and what we can’t. We can control how we spend our time and what we try to learn. We can control who we pursue and make strides to impress them. But there are other things we can’t control, both about ourselves and what other people like or don’t like about us.

Learning in games can be done by shuffling the cards and trying again. Learning in real life can be much more complicated.