By Megan Reddicks Pignataro

It comes as no surprise to us today to hear that an upcoming blockbuster movie to hit the big screen will be offered in 3D. Does our experience of seeing Avengers: Endgame in 3D change compared to more traditional 2D formats? Personal preferences aside, the creation of a visual experience which convinces the human eye to believe the optical illusion takes its cues from centuries of global artistic practices. My project at the Digital Scholarship Center aims to visualize one of these artistic techniques, which suggests a deep spatial recession to the human eye with very minimal actual depth.

The Italian Renaissance Goes 3D

In the early decades of the 15th century, the Florentine artist Donatello sculpted a marble figure of St. George at the church of the Orsanmichele. Beneath it is a small marble relief panel, which illustrates the legend of St. George Slaying the Dragon.

This relief panel was remarkably unique in its use of extremely shallow carving in order create the sense of spatial recession into the fictive distance. The term that came to be associated with this squashed and sketch-like sculpting is schiacciato.

Donatello’s schiacciato is a critical early example of the creation of atmospheric perspective that visually records how objects and space become fuzzy to our human eye as they recede into the distance. The St. George relief becomes a revolutionary object for contemporary artists to study this phenomenon, thanks to its very public location in the city.

How Did They Do That?

My project for the Digital Scholarship Program focused on visualizing how schiacciato works on the sculpted surface and how we can computationally see an Italian Renaissance sculptor’s illusionistic carving technique. The results will factor into a chapter of my dissertation on the creation of atmosphere in fifteenth century sculpture in Florence.

As there are no firmly attributed Donatello works featuring schiacciato on the Eastern seaboard, I opted to look at a sculpture from one generation later by Desiderio da Settignano, who adopted Donatello’s technique.

I could (and did) physically create this visualization through Photoshop in a very tedious process of coloring. A computational method would spare this work and also increase the level of accuracy that I could only estimate by eye.

Desiderio da Settignano (Florentine, c. 1429 – 1464), Saint Jerome in the Desert, c. 1461, marble, Widener Collection 1942.9.113

Vogue Photoshoot on a Budget

In collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, I used photogrammetry to create a 3D model of Desiderio da Settignano’s St. Jerome in the Desert relief panel in order to topographically map the varying depths of carving.

A 3D model allows for object manipulation in ways that would be prohibitive due to cost, object fragility, and museum labor as Agisoft only requires high quality photographs. Topographical mapping could be achieved with specialized laser scanning from above which is not necessarily available to art historians traveling to see particular objects abroad and is also cost-prohibitive. The mapping can be visualized onto the surface of the 3D model to demonstrate the levels of carving depth.

The photoshoot of the St. Jerome in the Desert took place on March 4, 2019 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. While approved by the museum’s imaging department, the use of a tripod proved to be ineffective given the variety of heights and angles required for capturing the relief from 180 degrees horizontally and vertically.

In total, I took 551 photographs of the relief over the span of about 2 hours. The sculpture curator, Dr. Alison Luchs, was present to assure museum security staff that my presence so close to the object was not a threat.

Photoshoot at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Photoshoot at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The 3D Model and Mapping the Technique

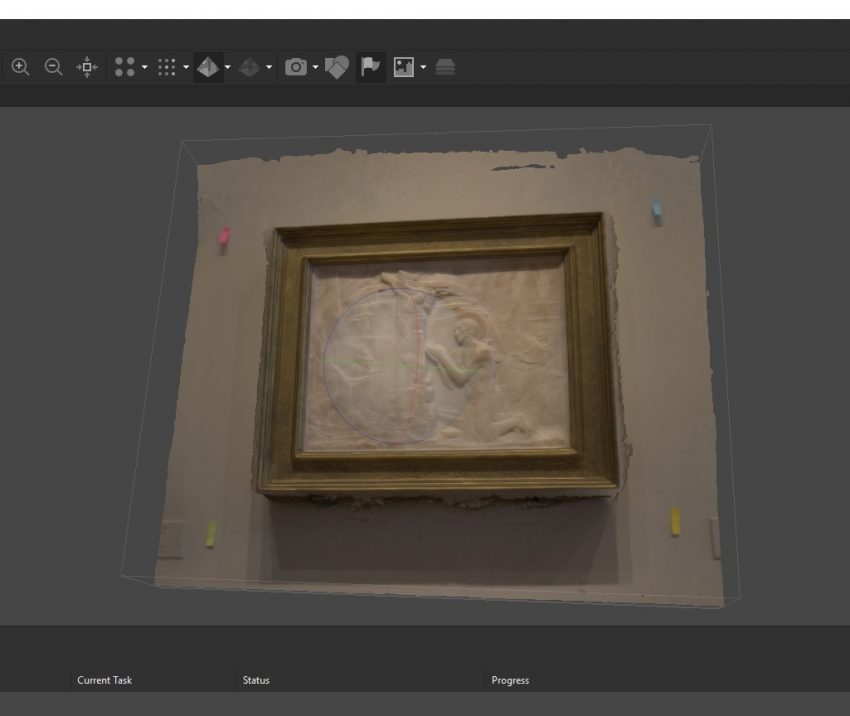

The photographs were imported into Agisoft. This processed the images and triangulated the camera positions around the relief sculpture to create a dense point cloud, stitching these various photographs together. The dense point cloud could them be generated into a 3D model and textured to match the relief and frame.

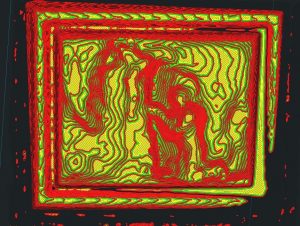

Agisoft poses a few complications for topographically mapping an object like the Desiderio relief which has no relationship to GIS mapping (ie. latitude, longitude, or altitude). This has led to a few different experiments into how an elevation map could be processed on top of this surface. One such instance was exporting the 3D model as an .OBJ file as if planning to 3D print it, and to analyze the hundreds of layers present. The image here shows a view of the middle of these layers where the outline of St. Jerome is clearly visible.

My next steps will utilize the architectural software Rhinoceros 3D to find alternative mapping functions that do not require GIS. This may include topographical cross-sections or surface mapping by layers.

Digital humanities software allows for less invasive and more cost-efficient ways to approach artworks that have public access restrictions. It is my hope that this project will continue current discussions in the art historical discipline about technological engagement to further our understanding of artistic practices throughout history, particularly those like 3D visualizations which continue today in motion pictures, video games, and more.