By James Kopaczewski

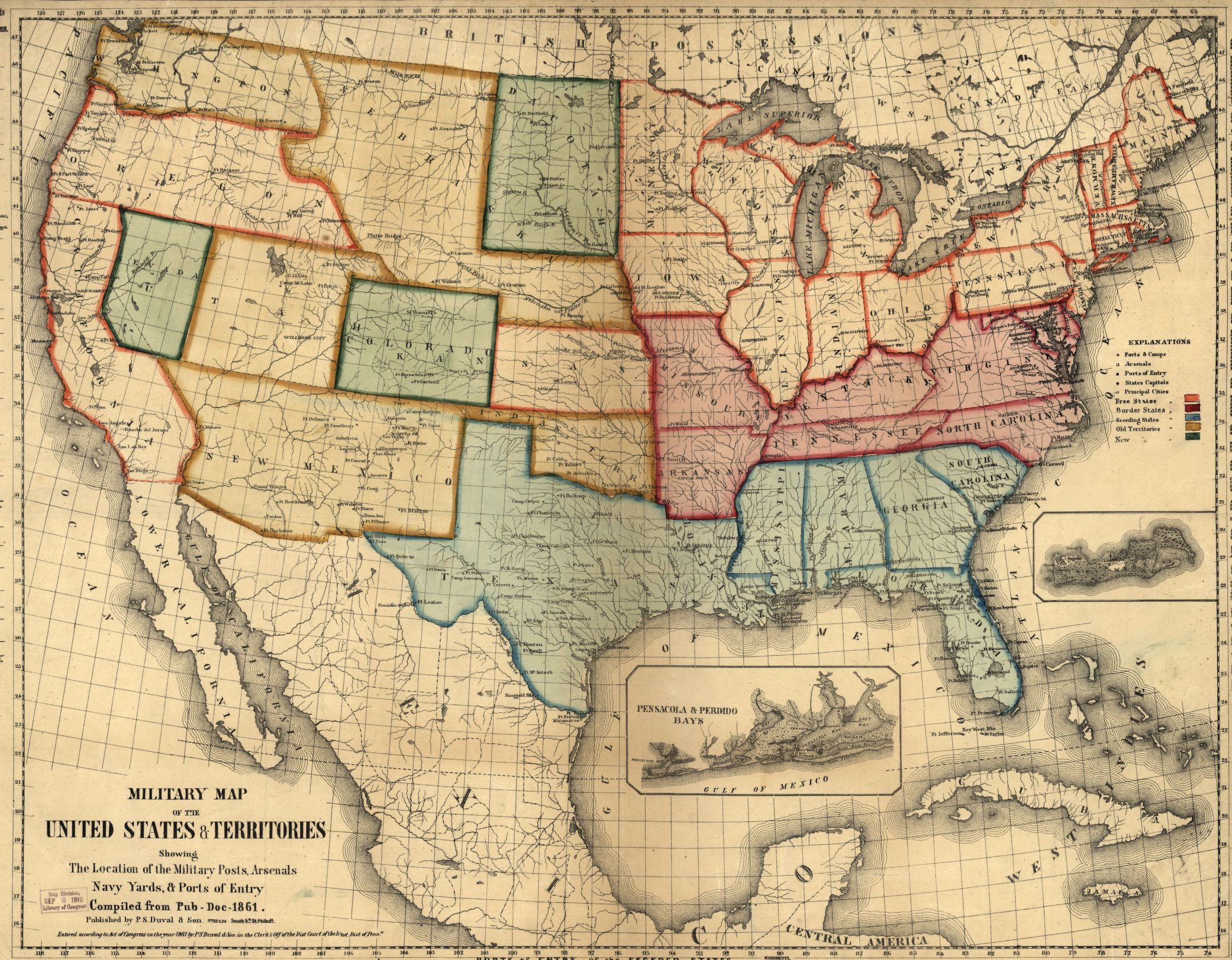

In a series of articles for the Civil War Times, Gary Gallagher, the John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War at the University of Virginia, questioned the validity of recent scholarship on the American West. In short, Gallagher argues that the West was not integral to the Civil War and that the real war occurred east of the Mississippi. He speculates that, “Americans polled in 1861-65 or in 1876 would not have placed the trans-100th-Meridian West anywhere near the center of either the war or Reconstruction.” Of course, even if Gallagher is correct in asserting that Americans saw the West and Civil War as disconnected, it does not prove that the West and the war were not in actuality deeply connected.

Gallagher’s arguments also reveal issues chronic to both Civil War and Western historiography. His use of the 100th Meridian as the demarcation line of the West speaks to an old debate among historians over the precise location of where the West begins. Gallagher uses an 1878 survey from United States Geological Service director John Wesley Powell to argue that the West began at the 100th Meridian. In doing so, Gallagher adopts Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis, which historians have struggled to disprove for generations. The Frontier Thesis argues that the West can be located by the existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of white settlement westward. The argument posits that because the West is a process of movement, it can’t possibly be connected with historical events located in the East. While the Frontier Thesis is flawed for a multitude of reasons, especially its disregard for native peoples living in the West, it has helped shape modern United States historiography.

Even though Gallagher is a widely admired and accomplished historian, his arguments underscore the traditional nature of Civil War Era scholarship. Not only have historians failed to think broadly about the geography of the war, they also have not critically dealt with digital methodologies. Until the early 1980s, Civil War historians almost exclusively studied political ideology, military maneuvers, and experience on the battlefield. Even as scholarship has pivoted towards race, gender, sexuality, and disability, the incorporation of digital methods into Civil War history has remained inconsistent.

Civil War historians were some of the first historians to work with the digital humanities. In the early 1990s, historian Edward Ayers and a team of graduate students created the Valley of the Shadow project, which attempted to reconstruct communities displaced by war in the Shenandoah Valley. Cornell University also digitized the full records of the Union and Confederate militaries in a project titled, The War of the Rebellion. And, yet, the field of Civil War history never followed up on these early projects or fully invested in digital methods. Even as fields, such as trans-Atlantic and urban histories, regularly utilize GIS and textual analysis, Civil War history has largely remained tied strictly to the paper archive.

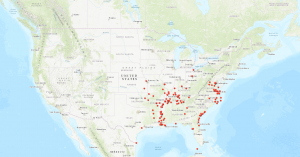

GIS offers historians with the ideal medium to re-conceptualize the geography of Civil War America. By mapping the location of contraband camps and reservations, we find that the Civil War was a national event that occurred in locations far from the American South.

The above map indicates that the contraband camps, which were ad hoc refugee camps for freedpeople inside Union lines, were most assuredly located in the West. Out of the roughly 220 contraband camps, 55 were located west of the Mississippi River. For instance, camps were located in places, such as Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, all of which are universally accepted as Western. Even after Appomattox, freedpeople migrated to the West to escape the failure of Reconstruction and the implementation of the Black Codes, a series of local laws aimed at restricting the freedom of African Americans.

Data on Native American reservations indicates that the West was intricately connected to national ideas about the Civil War. Throughout the Civil War, the federal government via executive orders and treaties established 116 reservations. While many of these reservations had long been settled by native peoples, the federal impulse to codify native lands suggests that federal policymakers were concerned with the West as a potential theater of conflict. In order to quell support for the Confederacy among native peoples, the United States government sought to entice native societies open to negotiation and punish those in defiance of federal rule.

While the data cleaning and GIS tools presented here are fairly simple, they provide examples of how easily Civil War historians can incorporate digital methods into their research. Historians don’t need decades of training to model data about the Civil War. In fact, tools, such as ArcGIS, Carto, Neatline, NodeGoat, and QGIS, present historians with the ability to create simple but flexible maps. As long as historians follow outdated methods, broader conceptual and geographic understandings of the Civil War will remain elusive. The digital humanities offer historians with the methods necessary to rethink how Civil War history is written.