By Kaelin Jewell

In the last few weeks, news organizations including the New York Times and National Geographic, have reported the discovery of more than forty shipwrecks at the bottom of the Black Sea. All astonishingly well preserved, the wrecks range in date from 9th-century Byzantium to the 17th-century Ottoman Empire and are currently being studied by the Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project (M.A.P.), an international team organized by the Centre for Maritime Archaeology at the University of Southampton in Britain. In addition to documenting all aspects of these wrecks, archaeologists are creating digital models of them using photogrammetry, a process that uses computers to stitch together digital photographs of landscapes, buildings, objects, or, in this case, shipwrecks to create 3-dimensional models. In recent years, as technology has become more and more accessible, archaeologists are turning towards photogrammetry as a useful way of creating digital topographic images of their sites, both above ground and underwater.

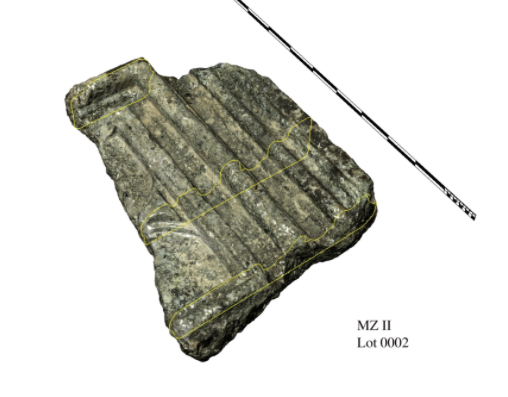

At the underwater site of Marzamemi II, located just off the coast of southern Sicily, an international team of scholars is investigating a 6th-century shipwreck, the cargo of which included large pieces of stone architectural sculpture. The fragments include gray-streaked Proconnesian marble columns, capitals, and chancel screens in addition to large slabs of verde antico stone in the shape of an ambo, or pulpit.

The presence of partially-preserved crosses on a few of the chancel fragments along with the distinctive shape of the ambo led the site’s original excavator, Gerhard Kapitän, to interpret the cargo as making up the interior architectural sculpture of a ca. sixth-century Christian church.

Described by Dr. Justin Leidwanger, director of the Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Project (MMHP) and Assistant Professor of Classics at Stanford University, as a sort of “flat pack” monument, the wreck provides important evidence for the transport of architectural sculpture across the Mediterranean during the reign of Emperor Justinian (527-565 CE), patron of Constantinople’s famous Hagia Sophia.

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to chat with Leidwanger about the site, which was reopened in 2013 under the auspices of Stanford University and the Soprintendenza del Mare in Sicily. Not only is the MMHP’s team interested in documenting and excavating the remains of the shipwreck’s cargo, but they are actively employing photogrammetry and structured light scanning as a way to create digital 3D models of both the site as a whole and the artifacts discovered within its boundaries.

According to Leidwanger, the MMHP’s use of digital tools “allow us to ask new research questions about the shipwreck cargo, while also opening a world of new possibilities for more meaningful engagement with heritage both locally and globally.”

I would like to extend my thanks to Justin Leidwanger for generously sharing images of the Marzamemi II project. Be sure to check out the Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Project’s Facebook page for the most recent news regarding this fascinating site!

Further Reading:

Kapitän, Gerhard. “The Church Wreck off Marzamemi,” Archaeology 22:2 (1969): 122-133.

Kapitän Gerhard. “Elementi architettonici per una basilica dal relitto navale del VI secolo di Marzamemi (Siracusa),” Corsi di cultura sull’arte ravennate e bizantina 27 (1980): 71-136.

Leidwanger, Justin and Nicolò Bruno. “Marzamemi II ‘Church Wreck’ Excavation: 2013 Field Season,” Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea 10 (2013): 191-198.

Leidwanger, Justin and Sebastiano Tusa. “Marzamemi II ‘Church Wreck’ Excavation: 2014 Field Season,” Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea 12 (2015): 103-115.

Leidwanger, Justin and Sebastiano Tusa. “Marzamemi II ‘Church Wreck’ Excavation: 2015 Field Season,” Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea 13 (2016): 129-143.