Written by Liz Rodrigues

Once I had assembled the early 20th century US immigrant autobiographies readily available on Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive, I needed to assess its quality and what methods might be usefully revelatory given its size. At around 50 books, it wasn’t large enough for any kind of machine learning classifier exercise. It was, in fact, on the small side for the most common forms of so-called distant reading. There was also another complicating problem for the majority of texts–they were full of typos and incomprehensibilities from the error-laden process of optical character recognition transcription. Without a good way of correcting them, even the most basic forms of topic modeling would likely be of little use. (Perhaps there is a way of estimating the error rate at least, but I wasn’t sure if that would be helpful.)

Faced with the prospect of many solo hours of hand correcting, I made a decision to shift the scale of my research at least temporarily. I figured that by using a small number of texts from the human-created, human-corrected Project Gutenberg, I could at least do some meaningful exploration.

I realized that my idea of modeling immigrant narrative implicitly assumed there was some way of tracking national affiliation textually. The most obvious place to start seemed like mention of country name. I also shifted slightly to a comparative look at autobiography and fiction, and so Mary Antin’s The Promised Land & Abraham Cahan’s The Rise of David Levinsky became my test cases. These are both highly canonical texts for studying US immigrant narrative, and both available on Project Gutenberg.

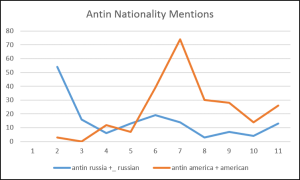

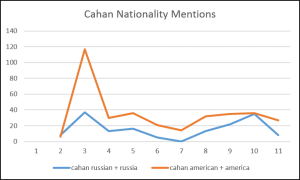

My first go was to look at mentions of the key nation states–in both cases America and Russia–using Voyant’s counting & visualization tools.

In Antin, an initial prevalance of “Russia” or “Russian” is, in the third quarter or so of the best, displaced by an even greater prevelance of “America” (see note below) or “American.” America/n retains its dominance in the closing segments, although Russia/n rises in parallel. For Cahan, the novelist, America/n is dominant throughout, with a brief intersection at the beginning of the final segment.

While these texts show a strikingly different pattern of mention Russia & America, they both seem to suggest that America predominates their thoughts at the end. Of course, this is an assertion and a proxy measure that would need to be tested by close reading–their mentions of the America could be denunciatory or self-distancing rather than affiliating.

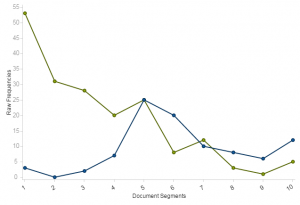

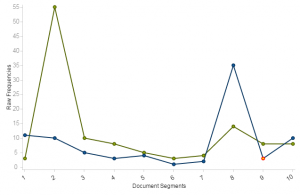

The interesting part of this process, though, came after I had done more in-depth work with named entity recognition & mapping. In the process of cleaning that data, I realized that, in fact, nation state names were not the primary mode of identification for these narrators’ homelands. Russia was actually for both the name of an occupying power. They instead identified more frequently with village names in occupied countries: Polotzk, Belarus for Antin and Antomir, Lithuania for Cahan. The mentions of Russia are likely for intelligibility to a US audience. So, I re-charted mentions.

Antin: mentions of “Polotzk” charted in green, “America” charted in blue

Cahan: mentions of “Antomir” charted in blue, “America” charted in green

For Antin, plotting Polotzk vs. America shows a much tighter story. Polotzk still dominates the first half, until America spikes at almost the exact midway point. From then on both remain relatively close in parallel.

For Cahan, plotting Antomir vs. America shows a much sharper divergence between the first and second halves. America spikes right at the beginning, but Antomir spikes strongly at the end, and actually has (it looks like) one additional mention in the final segment. One mention isn’t, perhaps, noticeable to the casual reader, but it shows a competing presence of both national spaces in the narrator’s mind rather than a clear switch to the US, the country to which the main character has immigrated.

The primary lesson I learned, here, is that the granularity of place name matters both for modeling the text and for understanding the historical context of the works at hand. These immigrants did not narrate their movement as being primarily between countries–it is also between much more specific places.

Note 1: neither text mentions “United States” much at all (7 times in Antin and 13 times in Cahan). Arguable, “America” is as much an idea as a place name & the official place name gets little attention.