By Danielle A Guimaraes

With the constant development of tools for visualization, digital historical reconstructions are becoming increasingly popular. From video games to scholarly publications, people are fascinated by the idea of being able to visualize and sometimes interact with an environment that has often changed or completely disappeared. These reconstructions also serve a variety of purposes—from showing a specific moment in time, to demonstrating urban changes, and even trying to interpret how people would have interacted with a certain space. In this post, I will explore some interesting historical reconstructions that I have encountered in my research. As I explained in my last post, I am currently working on a digital reconstruction of Piazza San Marco in Venice through time, and here I will discuss a couple of projects that have inspired my own.

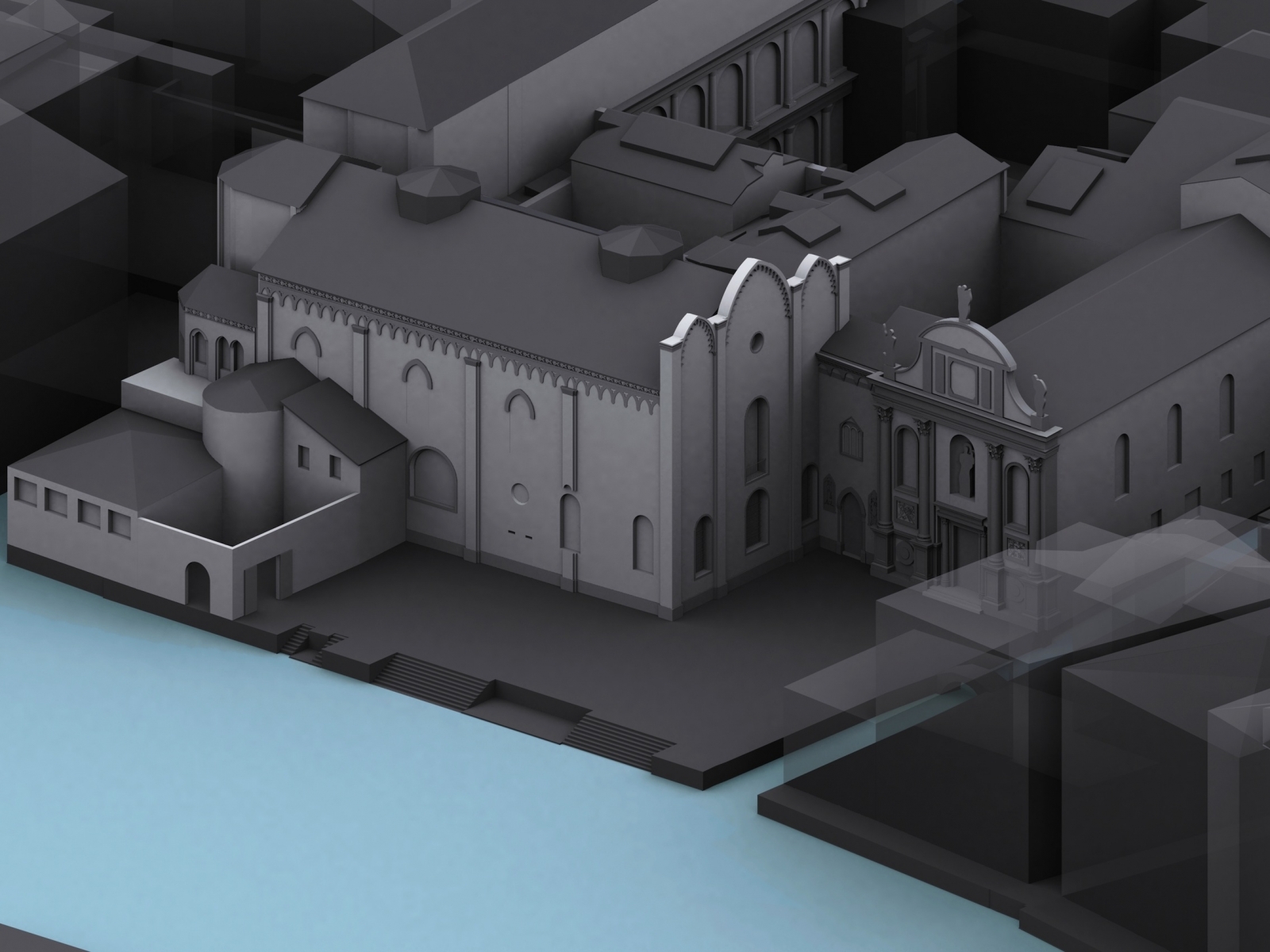

In my previous post, I mentioned two projects that have served as models for my study: Visualizing Venice and Virtual Paul’s Cross Project. The first, a collaboration between Duke University, Università IUAV di Venezia, and Università degli Studi di Padova, focuses on the digital reconstruction of various areas of Venice and how these have changed over time. The program is also deeply committed to training students in these digital tools, and every summer they offer a two-week workshop at Venice International University that concentrates in one of their current projects. Last summer, I had the opportunity to participate in the program, and this experience was crucial to the incorporation of digital tools into my own research. If you click on the image below, you can see a video of one of their past projects, which concentrated on the area of the present-day Gallerie dell’Accademia, one of the main art museums in Venice. And to know more about their current and past projects, check out their website: https://digitalhumanities.duke.edu/visualizing-venice

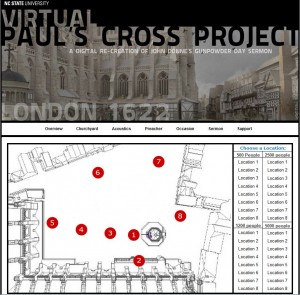

The second project I had mentioned was the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, developed by a group of scholars at NC State University. The study explores public preaching in early modern London, and it employs architectural reconstructions combined with acoustic simulations to allow users to experience the Paul’s Cross sermon delivered by John Donne on November 5, 1622. To read more about the creation, development, and outcomes of their project, you can check out their website: http://vpcp.chass.ncsu.edu/.

If you are specifically interested in exploring the acoustics of the space, I suggest that you play with their ‘Explore Audibility’ feature at: http://vpcp.chass.ncsu.edu/experience/. This tool allows you to select different ways to experience the space according to where you are located and how big the crowd is.

As you can see from these brief descriptions, both projects explore historical reconstructions in a different manner, showing the potential of digital tools. While Visualizing Venice focuses on urban changes through time, a successful approach to a constantly changing city like Venice, the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project concentrates on a specific day and location, functioning as a case-study for public preaching in early modern London. Even though both projects are visually engaging, it is also clear that design choices were made according to the goals of each study. Another important distinction between them is their interactivity. These are some issues that I have also been considering in relation to my own project, and it is interesting to see how scholars have dealt with them in past studies. I hope these two examples have shown some of the great potential and outcomes of digital reconstructions!