Unlike the previous readings that we have done in class, Pedestal, Loom, and Auction Block, a chapter from Through Women’s Eyes: An American History with Documents by Ellen Carol Dubois and Lynn Dumenil, the authors use a combination of many primary and secondary sources while discussing true womanhood, early industrial women workers, and women in slave society. Alternatively, “Separate Spheres, Female Worlds, Woman’s Place: The Rhetoric of Women’s History,” by Linda K. Kerber uses predominantly secondary sources to make her argument. Although she does frequently reference Alexis de Tocqueville’s books illustrating his experience in America, which is considered a primary source, quite frequently. However, regardless of their differences both articles discuss the idea of “true womanhood” and “woman’s sphere” in early America, they both leave out a significant group of women in their discussion.

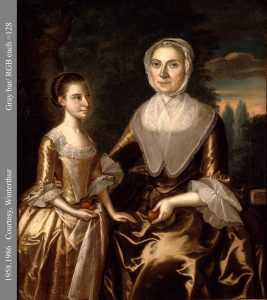

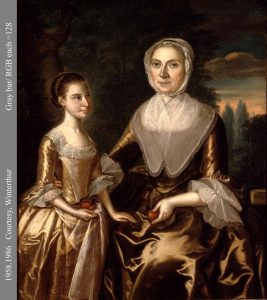

Both of the articles focus primarily on the experience of white women at the time. More specifically, on upper class white women. Poor white women were discussed as well, but in less detail and at less length. When the issues were discussed in a general sense it was typically referring to the experiences of just that narrow class. Kerber only briefly discusses the experience in the African American community by addressing the gap in the existing literature and making assumptions based on what was available[1]. This appears to be a significant drawback of using predominately secondary sources. The older studies which the author was using largely failed to discuss the experience of African American women at this time and because of that it was largely left out of her article as well. The issue was also discussed by Dubois and Dumenil, who did a much better job covering the experiences of both poor white women and African American women due to her wider sources. Pictured blow is Ellen Craft, an escaped slave with an amazing story that was only able to be told because of transcriptions created during the New Deal in order to document the real experience of slavery before all of the freed slaves died[2]. However, both articles completely fail to mention Native American women in a significant manner.

While the European influence in the trends noticed in early America is discussed, the contradictions that can be found in the Native American community are not referenced by Dubois, et.al, and only momentarily touched on by Kerber. Kerber mentioned briefly that the different gender roles in the Native American community caused the European settlers to view them as uncivilized. However, her coverage of the issue took up less than a paragraph[4].

Dubois and Dumenil say that to Americans at the time, it seemed ‘natural’ that women were suited to become teachers, take on domestic roles, and were sexually innocent. However, these feelings were only due to societal pressures in Europe[5], that were taken over to the United States. However, the gender roles that were already present in the land where the United States would eventually be born were quite different from those in Europe. While there were still somewhat separate spheres for Native American men and women, their circles overlapped more. For instance, they were both heavily involved in different parts of the farming process.[6]

———

[1] Linda K. Kerber, Separate Spheres, Female Worlds, Woman’s Place: The Rhetoric of Women’s History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 25-26.

[2] Dubois, Ellen Carol, and Lynn Dumenil. ” Pedestal, Loom, and Auction Block 1800-1860.” In Through Women’s Eyes: An American History with Documents, (Boston: Belford/St.Martins, 2012), 226.

[3] Dubois, Pedestal Loom, and Auction Block, 227.

[4] Kerber, Separate Spheres, 19.

[5] Dubois, Pedestal Loom, and Auction Block, 190.

[6] Brown, Kathleen. “The Anglo-Indian Gender Frontier.” In Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and

Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 20.

4

4