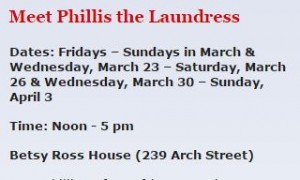

While the credibility of the story of Betsy Ross is debatable among the historical community[1], the American public continues to visit the Betsy Ross House in droves, flocking to learn about the fabled flag-maker and the story of the so-called “first flag.” Located on 2nd and Arch Streets in Old City, Philadelphia, Ross is believed to have lived in what is now the Betsy Ross House museum from 1776-1779, during which time, according to legend, she created the first American flag. Ross’s story became popular during the last third of the 19th Century.[2] With the help of her descendents, the story gained both popularity and widespread public acceptance. Despite persisting doubts in the credibility of the story of the “first flag” as constructed by Ross’s relatives, the house museum, opened in 1898, has continued to promulgate the idea of Betsy Ross as patriot and flag-maker. The museum creates a shrine-like atmosphere, focusing more on reconstructing fable than on factuality. However, while the museum itself is questionable in its representation, it provides insight into the larger issue of the way that women are portrayed in early American history. In honor of Women’s History Month, the Betsy Ross House featured appearances by a washerwoman, Phillis, who provided authenticity and a glimpse of what life was like for working women during the late 18th Century. This, rather than the myth of Betsy Ross, gave an effective and interesting look into the lives of 18th Century women. Questions of fact and myth aside, the Betsy Ross House serves an important function—to acknowledge and explain the lives of women in the 18th Century.

While the credibility of the story of Betsy Ross is debatable among the historical community[1], the American public continues to visit the Betsy Ross House in droves, flocking to learn about the fabled flag-maker and the story of the so-called “first flag.” Located on 2nd and Arch Streets in Old City, Philadelphia, Ross is believed to have lived in what is now the Betsy Ross House museum from 1776-1779, during which time, according to legend, she created the first American flag. Ross’s story became popular during the last third of the 19th Century.[2] With the help of her descendents, the story gained both popularity and widespread public acceptance. Despite persisting doubts in the credibility of the story of the “first flag” as constructed by Ross’s relatives, the house museum, opened in 1898, has continued to promulgate the idea of Betsy Ross as patriot and flag-maker. The museum creates a shrine-like atmosphere, focusing more on reconstructing fable than on factuality. However, while the museum itself is questionable in its representation, it provides insight into the larger issue of the way that women are portrayed in early American history. In honor of Women’s History Month, the Betsy Ross House featured appearances by a washerwoman, Phillis, who provided authenticity and a glimpse of what life was like for working women during the late 18th Century. This, rather than the myth of Betsy Ross, gave an effective and interesting look into the lives of 18th Century women. Questions of fact and myth aside, the Betsy Ross House serves an important function—to acknowledge and explain the lives of women in the 18th Century.

The Betsy Ross House museum was carefully organized and labeled in a way that reinforced “the cult of Betsy.” The rooms themselves were full of objects and reproductions that purportedly belonged to Ross, including a bible, a walnut chest-on-chest, Chippendale and Sheraton side chairs, her eyeglasses, and her petticoat. These items were displayed in different locations throughout the house and served to highlight different aspects of Ross’s life. The glasses and the bible were displayed in her bedroom, while downstairs in the cellar an interactive exhibit described foods Betsy would have eaten and how she was “so clever” for preserving them in her root cellar. The actor portraying Ross was a pretty young woman, sewing curtains in the room that functioned as the upholstery shop. She explained to passersby what she was working on, and described the experience of making the first flag.

Visitors who made their way to the cellar of the house during the month of March were greeted by Phillis, a freed African-American laundress, as part of the Women’s History Month event Women at Work in Revolutionary America. As part of the reason I chose to visit the Betsy Ross House, I made sure to ask Phillis about her work and her life. She explained that each laundress had her own route and neighborhood that she served. Although work was not usually contracted long-term, Phillis explained that she worked for the woman who lived in what is now the house museum on a monthly basis. However, most houses, she said, were simply a matter of luck and good timing—she would often go door-to-door and knock, asking the woman in charge of the house if the laundry needed to be done. I asked her if there was competition for work, and she said that although there were many laundresses, it was common for each washerwoman to stake out a piece of “territory”—usually several city blocks, in which she would work.. As I knew little about the lives of ordinary women during this time previous to this semester, I was interested to discover that, according to discover that, according to historian Carole Shammas in her article Female Social Structure of Philadelphia in 1775, only 2.3 percent of female heads of household in the Chestnut and East Mulberry Wards worked as washerwomen in 1775.[3]

Interestingly, it seems that Ross too was in the minority of female occupations, as only 4.6 percent of women in these wards worked as artisans, including glovers and upholsterers.[4] This sheds light on the fact that regardless of whether Betsy Ross sewed the first flag for George Washington, her occupation set her apart as a woman who, though married several times, pursued her trade and had a successful business making curtains, flags, and other household linens. Phillis the washerwoman and Betsy Ross, though very different from one another, shed light on the lives of women not through their great accomplishments as patriots, but rather through their occupations, which spoke to a level of confidence and self-assuredness regardless of the money they made.

Much of the Betsy Ross House felt rather contrived and at times overly-mythologized, but the Women at Work exhibit gave an interesting, insightful overview of women like Phillis, who more often than not are passed over in larger histories in favor of legendary figures like Betsy Ross. The majority of the house museum allowed me to see just how persistent and entrenched the Betsy Ross myth really is—the entire museum was organized around stories passed down from Ross’s relatives, who by 1870, had begun to promulgate the myth of Betsy Ross and the American flag.[5] There is little to no evidence, as Laurel Thatcher Ulrich points out in her article How Betsy Ross Became Famous, that Ross herself invented the flag’s design, and rather that she was simply hired to make Pennsylvania naval flags in 1777.[6] In fact, different versions of the flag abounded. However, Ulrich goes on to attest, it is not the flag that matters, but Betsy herself. Betsy Ross, the so-called creator of the flag and ordinary seamstress, holds a place in the hearts of the American people precisely because she was so normal.[7] She fills a void in early American history with her story—in a time swirling with romantic ideas and tales of the founding fathers, Ross provides a female figure—a patriot, a “talented businesswoman”[8], and a wife who, although she led an average life, has managed to cement herself firmly in the American popular consciousness. She represents a way for women to connect with the glorious American beginnings—a role that women like Phillis, whose lives were equally as average and equally important, are unable to fulfill. Due to her descendants’ carefully crafted and passed-down stories, Ross’s legacy endures and has become the stuff of legend. However, we must keep in mind the women like Phillis—the women who perhaps had no offspring, or whose descendants were unable to tell her story. For they, too, are the face of 18th Century America.

Works Cited

[1] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “How Betsy Ross Became Famous,” Common Place 8, no. 1 (2007). Accessed January 26, 2016, http://www.common-place-archives.org/vol-08/no-01/ulrich/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Carole Shammas, “The Fmeale Social Structure of Philadelpha in 1775,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 107, no. 1 (1983): 75.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ulrich.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.