In the article ‘Japanese American Women During World War II’, Valerie Matsumoto makes the statement that “the war altered Japanese American women’s lives in complicated ways”[1]. The rest of the article is a testament to that very fact, as Matsumoto simultaneously evokes the difficult hardships and the surprising advancements in the lives of Japanese women both during and after life in the internment camps.

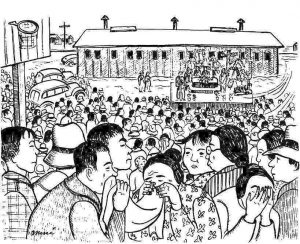

Having been completely uprooted from their homes and swept into the camps, despite the fact that the vast majority of the Japanese Americans were citizens with the same rights as any other American, life in internment camps was undeniably traumatic. Such notions are reflected in Miné Okubo’s graphic novel Citizen 13660, one of the few visual representations from the period created by an actual evacuee, which depicts the mixture of both anger, sadness and despair at the prospect of entering the camps, as seen in the image below.[2]

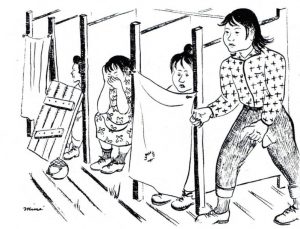

Life in the camps subsequently had a significant impact on family relations and affected all women in the camps. Poor communal facilities coupled with overcrowded barracks meant that, as Matsumoto contends, “the sense of injustice and frustration took their toll on a people uprooted, far from home”[3]. Again, these ideas are similarly evoked in Miné Okubo’s graphic novel, in which she draws out the complete lack of privacy and the cramped living conditions that the Japanese women had to face on a daily basis.

Despite these awful living conditions, Matsumoto also notes a sense of growing independence for Japanese women in the camps, fostered by the fact that both men and women received the same wages for work. This equity in pay, Matsumoto contends, subsequently gave women the opportunity to explore the variety of jobs available for them in the camps. However, what I found most surprising was that the camps had newspapers, such as The Mercedian, The Daily Tulean Dispatch and the Poston Chronicle, which subsequently gave women the opportunity to create columns specifically for women, particularly aimed at Nisei women. The content of these columns mirrored the mainstream periodicals of the time, varying from how to impress boys, take care of their skin, to what the latest fashions were and subsequently reflected a desire to keep morale high despite the depressing environment. Such notions can also be seen in Citizen 13660, in which the resourceful way people create furniture to gardens from next to nothing is inspiring. Okubo therefore shed’s light on how although the camps were unjust, the Japanese women and men were able to overcome the hardships they endured.

Ultimately, I think that this period of American history is widely understudied, and being from the UK, I have never even studied Japanese internment until now. Therefore, I think personal accounts, such as Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660 and the talk we were supposed to have with Lorna Uno, are vital for constructing an important narrative to a relatively ignored historical past.

[1] Valerie Matsumoto, “Japanese American Women During World War II” in Women’s America, ed. Linda Kerber, Jane Sherron De Hart, Cornelia Hughes Dayton, Judy Tzu-Chun Wu (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 535.

[2] Miné Okubo, Citizen 13660 (New York: University of Washington Press, 1983)

[3] Valerie Matsumoto, “Japanese American Women During World War II” in Women’s America, ed. Linda Kerber, Jane Sherron De Hart, Cornelia Hughes Dayton, Judy Tzu-Chun Wu (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 531.