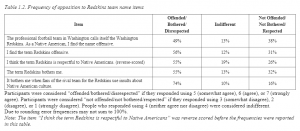

Half a year ago, psychologist Stephanie Fryberg and her colleagues published an article (supplementary materials) in Social Psychological and Personality Science on how Native American identity influences attitudes towards sports’ teams use of native mascots, with a particular focus on the infamous Washington Redskins. Jane Recker wrote a news article about the research for The Washingtonian. In it, Recker compares Fryberg et al.’s findings to those of previous polls:

In 2016, the Washington Post published a poll about whether Native Americans found the Washington Redskins’ name offensive. Ninety percent of respondents said they were not offended by the team’s name. The poll has since been used by Dan Snyder and other team owners as evidence that their Native American mascots are inoffensive.

But a new study from academics at the University of Michigan and UC Berkeley contradicts that data. In a scientific survey of more than 1,000 Native Americans, roughly half of the participants said they were offended by the Redskins’ name.

In Recker’s interview with Fryberg, she speculates that the profound indifference shown by the Native American respondents in the Washington Post poll is due to question order effects and social desirability bias:

They called people, as part of a larger study, and they had these items [about mascots] in there. One of the things that we know in science is that the questions you ask before and after influence the response. For example, if I asked you a really serious question about people who are dying in your community, and then I say, “By the way, are you offended by Native mascots?” you see how you can really influence people. People have requested to know what the items were and what order they were in. The second issue is that they called people. There’s very good data that shows when you do a call versus online, it changes peoples’ responses. When you call, people are more likely to give positive and socially desirable answers. And then they only allowed as answers to their question, “are you offended, are you indifferent, are you not bothered?” Native people telling a person they don’t know that they’re “offended,” that’s a strong emotion…We took the same question [the Post asked], but we gave participants a one-to-seven scale. So you can answer, “I’m somewhat offended, I’m moderately offended, I’m extremely offended.” We also didn’t call them, we allowed them to do it online. There’s no stranger or other person you’re trying to account for, [worrying] what they’re going to think about your response.

Since Fryberg et al.’s poll differs from the Washington Post‘s poll in many different ways we have a “small-n big-p” problem–we have only two studies that differ in so many different ways it is impossible to tease out what exactly explains the difference between their findings. Part of me wishes Fryberg and her team had retained the Washington Post‘s response set, or at least did a survey experiment and randomly assigned people to either the original response set or her response set, but the truth is replicating the Washington Post poll was only a secondary concern for these authors.

Alternative Explanations for the Difference Between the Post and Fryberg et al.

There are a couple of additional explanations for the differences between the two surveys. One is the Washington Post poll was fielded from December 2015 to April 2016, while Fryberg et al.’s survey was fielded more recently, and that maybe the cultural zeitgeist surrounding the Redskins has changed during the elapsed time. I could not find in Fryberg et al.’s paper the exact days their survey was fielded, but I am guessing it was probably late 2018 to early 2019, so around three years after the Washington Post study. Maybe over this time activists were able to mobilize greater antipathy to the “Redskins” name. This is a possibility but it is a weak one–2019 was not that different from 2016.

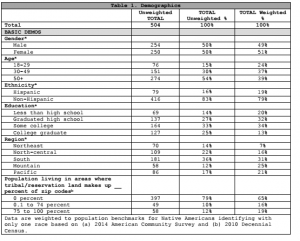

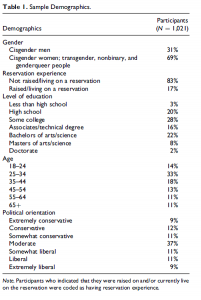

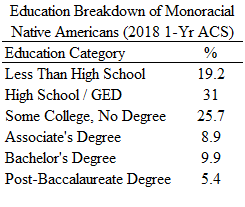

A more plausible explanation is that the two surveys’ samples used quite different recruitment strategies and thus you are not quite getting comparable slices of Native American opinion for the two time periods. Fryberg et al. sells their online survey as a strength–people are less susceptible to social desireability bias when doing a survey on the computer rather than the phone. On the other hand, in my view this is a serious potential weakness, since recruiting people online risks getting self-selection bias in ways that recruiting people through phone calls does not. The Washington Post sample is substantially older and less educated than Fryberg et al.’s panel, which is about what one would expect. The Washington Post sample is also educationally closer to the monoracial Native American population (according to the 2018 American Community Survey) than is Fryberg et al.’s survey, although the Washington Post sample is also better educated than the Native American population. From the Washington Post‘s demographic table I posted below, one can see the Post used sample weights to counteract the selection biases their phone poll introduced. As best as I can tell, Fryberg et al. did not use sampling weights. It is likely that the younger, more educated, and more online Native American respondents in Fryberg et al.’s sample are more attuned to the outrage over the offensive “Redskins” name than are the less-educated, older Native American respondents in the Washington Post poll. My strong suspicion is that if Fryberg et al. used a sampling strategy consistent with that of the Post the differences between the two findings would be much more muted (if they exist at all).

I would guess that this is not terribly relevant for Fryberg et al.’s central research question–the influence of Native American identity on attitudes towards team names. It is much more consequntial for the univariate question of how much Native Americans find team names offensive, and in my view, it was a mistake for Fryberg to use that as a hook for media attention.

I also wonder if there are differences in how the two surveys categorized subjects as Native Americans. It appears the Washington Post poll asked respondents to place themselves in one of seven racial categories: Asian, Black/African American, Native American, Pacific Islander, White, Mixed Race, and Other. Only people who answered “Native American” were included in the study. Fryberg et al. indicate they also used some kind of self-categorization into the “Native American” category as a criteria for inclusion in the study, but it was not clear to me if this includes individuals self-categorizing as just “Native American” or as “Native American” plus some other group. According to the 2018 5-Year American Community Survey, 2.7 million Americans self-categorized solely as “Native American”. 2.9 million Americans self-categorized as “Native American” plus one or more other group (people self-categorizing as “Native American” and “White” make up 1.9 million individuals alone). Does Fryberg et al.’s study just focus on the “monoracial” Native Americans, or do they also include the “multiracial” Native Americans? I would guess that it is the former, since a sample including multiracial Native Americans would probably show even fewer Native Americans taking offense to the “Redskins” name, but I do not really know.

Too Many Notes

I want to make some other points about the Fryberg study.

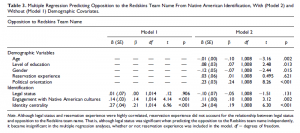

One, the paper had a really sophisticated approach to measuring Native American identify. While their sample just consists of people who categorize themselves as “Native American”, they measure different ways in which people identify as Native American: there’s legal status, there’s engagement with Native American cultures, and there is identity centrality.

Two, having said that, I probably would not have shown the simultaneous effects of these three measures of identity in the same model–I was really curious how people who are “legally” Native American react to the Redskins name, while Fryberg et al. show that, if anything, individuals who are legally Native American are less likely to agree the Redskins name is offensive, but they also control for the other measures of Native American identity. Unless you are doing some kind of mediational model, there is not much point in comparing two Native American individuals, one legally defined as being Native American, the other not, but both have the same engagement with Native American culture and being Native American is equally central to their personal identities.

Three, the authors to their credit place a lot of information, including their survey, online, which is great for open science.

Four, if you look at the survey, you will see they asked their respondents a lot of questions. In addition to 12 questions asking about feelings towards Native American mascots and team names and 67 questions about Native American identity (of which they used only 24 in the published study), they asked an additional 47 questions asking subjects’ opinions about various Native American issues that are not touched on in the article. I really worry about the cognitive load these lengthy surveys put on respondents and I wonder about the quality of the data one gets. Like many other researchers, Fryberg et al. attend to measures of reliability like Cronbach’s alpha, but I am not sure that a high reliability means a researcher does not have to worry about noisy measures. A high Cronbach’s alpha just means that the items in the measure have a healthy correlation with each other. But if respondents are tired, and they see a block of questions asking about similar things, they might just quickly decide on a general attitude and answer each question with that in mind without really thinking about the content of the questions (or really the point of the questions). Thus, a block of questions could have a high reliability in the sense that people’s answers to them are correlated, but the overall scale may be an unreliable measure of the concept in the sense that if you asked the same person to take the scale on a different day they might settle for a very different general attitude that drives their answers to the items. Having taken tedious surveys before this does not seem like a far-fetched scenario to me.