Women in U.S. History have always been a crucial component to the development of Colonial America whether one wants to believe it or not. Countless primary sources rise up and provide us with essential details about our ancestors and how life used to be. Unfortunately for us today, there aren’t many pieces of evidence from females because men dominated in every facet of life during Colonial America. In Susan Klepp’s “Revolutionary Bodies” and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s “How Betsy Ross Became Famous” we see a glimpse of how women were viewed and treated by the mass society during Colonial America.

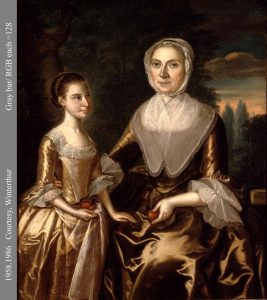

In Klepp’s “Revolutionary Bodies”, she talks about the metaphoric language that was used to describe a pregnant woman as “fruitful” and how these descriptions disappeared with the declining birth rate. There were common themes during this time, mostly originating from Europe, that reflected certain motives for a family to reproduce at such a large scale. The idea of marriage was directly connected to complex deals for economic survival. There were cases where spouses were selected based on whose family had a nearby plot of land or farming tools needed for their crops. The idea of marriage and reproduction was a political and economic institution that served important functions in society. The power of the church also played a significant role in influencing the relationship between a man and woman. The relationship between God and man proved to be a stronger bond than between the couple. The idea of free choice in marriage only served to reinforce the wife’s duty to serve her husband. John Winthrop once said, “The woman’s own choice makes such a man her husband; yet being so chosen, he is her lord, and she is to be subject to him” (Winthrop 1853). There was a correlation between fertility rates and education. Klepp mentions, “the higher the educational attainment of women, the lower fertility rates” (Klepp, 915). Perhaps this suggests that as more and more women became educated on the matters of mass fertility and personal human choice, it contributed to the steady decline from the average seven children to an average of two today. There was an incentive to having boys over girls. The oldest son would naturally inherit the family home or farm. Women during this time, once married, any property that a woman brought to the marriage would be directly inherited by her husband. Klepp’s essay provides insight to the transition of the feminist mindset and where the modern family today stems from.

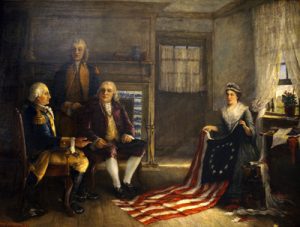

Betsy Ross plays into the same narrative of women establishing a voice for themselves. It’s hard to think of women that stand out like the men who built the country we know of today. The fact of the matter is there were women just as important as these men and contributed a great deal to our country. When I think of women like Betsy Ross, I can’t help but think of the movements that were created by the Grimke sisters. Angelina and Sarah Grimke hailed from the South when the institution of slavery was nearing the peak of its time. They both declared themselves abolitionists and desired equality for men and women. They were the first to push the boundaries of women’s public speech towards women’s rights and question African American rights. However, when you think of famous abolitionists you quickly think of names like Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. However, women were very much involved in the abolitionist ideas like men were. Like Ulrich says, “Betsy became famous, not because of what she did or did not do in the 1770s, but because her story embodied nineteenth-century ideas about the place of women” (Ulrich, “How Betsy Ross Became Famous”). Betsy Ross’s contribution to the American flag helped challenge the notion that only men created the new nation thus becoming a product of recognition for women in our country.

The Grimke sisters lived to see the end of slavery and the beginning of the women’s rights movement.