Current State of Affairs

Last month, Circular Philadelphia released a comprehensive policy guide on the current state of single-use plastic legislation in Philadelphia.

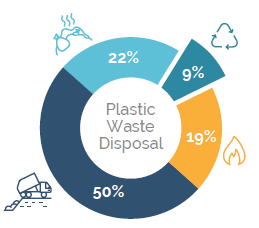

Despite the clear negative impacts of plastic production on the environment and our increasingly overwhelmed waste management systems, single-use plastic production has doubled in the last 60 years. This increase in production was exacerbated by the pandemic through online purchasing of delivery and takeout food orders increasing the demand for single-use packaging and food containers. The pandemic also hindered Philadelphia’s ability to manage plastic waste, as sanitation workers faced both an overwhelming amount of waste to clean up and a disproportionately high risk of exposure to COVID-19 due to their working conditions. This forced the city to prioritize trash management over recycling, leading to a drop from 22% in 2019 to a low 8% in 2022.

Despite the surge of single-use plastic during the pandemic, Philadelphia has recently taken several steps in the right direction when it comes to managing waste. The city increased on-time trash collections from 56% in 2021 to 96% in 2022 and added 150 new personnel for trash collection. Philadelphia also passed its ban of single-use plastic bags in 2022. A recent report found that after three months, reusable bag use doubled, and plastic bag use fell to almost zero.

Possible Solutions

Circular Philadelphia also reports that there are steps the city can take to reduce plastic waste even further in as short as a few years. The easiest solution to waste is legislation that bans or punishes single-use plastic, a measure that has already been used to eliminate plastic bag use in states such Hawai’i, Maine, and New York as well as municipalities such as Boston, Los Angeles, Seattle, and of course, Philadelphia.

Other methods include shifting responsibility for plastic consumption away from consumers, and instead pushing producers to reduce the amount of single-use plastic they use in their manufacturing and shipping process. In 2022, California passed a law that requires all packaging to be either recyclable or compostable by 2032, which is expected to help reduce plastic packaging by 25% and requires 65% of all single-use plastic packaging to be recycled within the following decade.

Another possible option is utilizing market-based solutions. Market based solutions often rely on a change in behavior from the consumer based on new trends or beliefs about what is socially favorable/acceptable. For example, it is favorable to like and protect animals, which made purchasing reusable straws popular when plastic straws were linked with harming sea turtles. But here are also several opportunities for change to come from the producers, such as manufacturing companies replacing traditional plastic bags with ones made from bioplastics, or stores offering reward points to customers who use reusable bags. A single cure-all solution for single-use plastic waste will be difficult to find, but combining several methods is a great start for achieving a waste-free future.

Circular Philadelphia’s Plan

Circular Philadelphia makes the argument that simple but thorough legislation informed by practices in other cities and regions is likely the best way to achieve fair, consistent, and measurable change when it comes to plastic waste in Philadelphia. Their recommended solution is a three-step legislation mechanism that eliminates certain single-use plastics from the take-out operations of restaurants’ and other prepared food establishments

Step 1. Ban certain single use plastics for take-out food

The most straightforward step to this process is banning items that are commonly littered after use, which includes polystyrene containers, plastic straws/cutlery, and plastic lined cups.

Step 2. Encourage a shift to reusable containers by imposing a fee on continued use of single-use plastics for take-out food

In order to encourage businesses to stop using any single-use items that remain unbanned, Philadelphia can incorporate an inspection for single-use plastics into the responsibilities of the Health Department and charge a fee for restaurants that are not compliant. The success of this part relies on its enforceability, which means it would mainly apply to places with food establishment licenses. It also requires flexible definitions for what is single-use, recyclable, compostable, reusable, etc. so that the city can update standards based on the available systems in its recycling department.

Step 3. Reinvestment of fee proceeds to clean up Philly and create a transition fund

Fees from noncompliant businesses would then be reinvested into waste management practices such as street sweeping, public trash cans, and assistance for businesses trying to switch to reusables.

Can It Be Done? Will it Work? Is It Worth It?

Short answer, Yes! Circular Philadelphia has already worked with the Health department to create a system of identifying restaurants that have reusable containers, meaning the framework is already in place to help more businesses comply with the proposed legislation.

If this legislation were to pass, Circular Philadelphia estimates that the benefits would include reducing the $48M spent on annual litter clean up, lowering food packaging costs from $0.29 per use for single-use to less than $0.01 per use by leveraging reusable containers, and addressing concerns such as microplastic consumption and the impacts of climate change.

Single-use Plastic and Campus Life

If these proposals were adopted, things could really change around campus. The multitude of student-serving food trucks, who are not owned or operated by Temple University, but under the jurisdiction of the city, would be on the hook for any plastic utensils and Styrofoam containers they distribute.

The majority of restaurants students eat “at” on campus don’t have indoor, or any, seating options and also lack the facilities to wash the number of dishes needed to meet rush hour demand. Reusable options available to other restaurants, such as metal utensils and sturdy dishes, generally aren’t viable for food trucks or “the Wall” vending pad by Mazur Hall. Students also tend to be on the move and use takeaway options in between classes, which would mean carrying around a dirty reusable plastic container. Unfortunately, this is considered a major inconvenience to a lot of students, and they’re not going to bring their own reusable containers if they still have the option for disposables.

All-encompassing waste policies like these — with real teeth and that extend beyond just the Aramark-owned and operated campus dining providers — could instigate broader behavioral and operational change across the city and on campus, especially with the massively popular food trucks. Until then, students can get us closer to a sustainable and waste free future by joining the fight for meaningful policy change, doing their best to use reusables themselves, and supporting those local businesses who are leading the way.