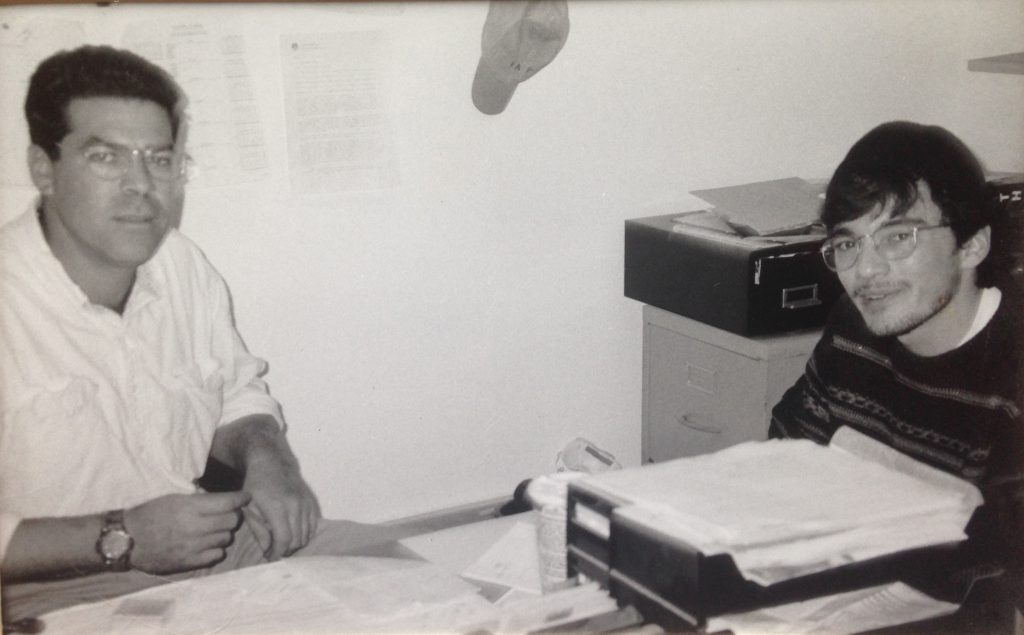

There is a framed black-and-white photograph in my office that depicts Tim White, a former head of the Workshop on the Water at Philadelphia’s Independence Seaport Museum, fitting a centerboard case into a wooden boat under construction in his shop. I took the photo myself way back in 1995 while doing field research for my undergraduate thesis project. It captures at least two moments. One is evidentiary: a simple act of boatbuilding. The other is more oblique: a young photographer in a strange city, excited by ideas, fascinated by boats, and emboldened by the documentarian’s gaze.

It was that second moment—not the first—that I went hunting around for in my old field notes sometime toward the end of my first year on the tenure track. I had come full circle, landing back in Philadelphia after years away. And yet, life and work in the university hadn’t turned out to be quite what I hoped for. Despite some bright spots, I found myself pretty quickly surrounded by unclear expectations, combative colleagues, and worse than crippling bureaucracies. Disciplinary orthodoxies turned out to be far more entrenched than I had suspected. More broadly, the in-crowd hierarchies that prevail across academia wore deeply on me, and still do. I found it harder and harder to recall what it was like to be excited by ideas, to be fascinated by anything, to be bold.

The photo of the boat shop, I hoped, would be a reminder, encouragement to revisit the things and places that had put me on this course years ago. And so it was. Before long I had reacquainted myself with the Seaport Museum, finding there colleagues who remain today among my most valued. I even dusted off some old boat research and found a few new projects along the way.

But the most important memories buried within that old photo had less to do with WHAT ideas excited me back then, than with HOW I got excited about ideas in the first place. I thought about the museums that thrilled me when I was a kid. I thought about how much I loved woodshop in high school. I thought about learning to do field research at the American Folklife Center and with the National Park Service. And I thought about professors I had respected for abandoning the classroom whenever it made more sense to show students how things work than to tell them.

Since then I’ve sought in my teaching to flee campus, or at least to get out of the classroom, whenever possible. I’ve tried it all: fieldtrips, outreach, partnerships, scavenger hunts, bus rides, walking tours, digital meet-ups, throwing pots, really whatever it takes. This semester I’m pushing further by staging an entire semester of course meetings at, where else, the Independence Seaport Museum. More than two decades since taking that photo of Tim White in his shop, I’m returning to the same spot with my own students to stage the LESLEY Documentation Project. Tim’s not there any more, but the boats are, and so is the shop, and amid all of it we’re getting excited about ideas that are all but impossible to conjure in the stubborn fixity of a seminar room.

The modern American university is a difficult place, run through with contradictions and inequity. Much that is good remains there, but I’ve become convinced that to find it we must step away as often as we can. Doing so, in my case anyway, amounts to an act of self-preservation. And for my students, especially in this age of anger and anxiety, learning to preserve ourselves may just be the most important lesson.

_____

A bibliography of the rise, fall, and rise of my excitement about maritime pasts:

- “Boatbuilding Documentation in the Archive of Folk Culture” (finding aid), Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, 1995, https://www.loc.gov/folklife/guides/Boatbuilding.html.

- “The Pennsylvania Boatbuilders Project: Shaping a Tradition,” in Robert D. Yearout, ed., Proceedings, Tenth National Conference on Undergraduate Research, Volume I (Asheville: The University of North Carolina at Asheville, 1996), pp. 101-05.

- “Pennsylvania Boatbuilding: Charting a State Tradition,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 65 (Spring 1998): 170-89.

- “The Shenandoah River Gundalow: Reusable Boats in Virginia’s Nineteenth-Century River Trade,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 118 (December 2010): 314-49.

- “USS Olympia Summit Report,” with Carly Goodman on behalf of the Temple University Center for Public History, commissioned by the Independence Seaport Museum, August 2011.

- “A Most Complete Whaling Museum”: Profiting from the Past on Nantucket Island,” Museum History Journal 8:2 (July 2015), 188-208.

- ““Save the Olympia!”: Veterans and the Preservation of Dewey’s Flagship in Twentieth-Century Philadelphia,” under review with the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography.

- Ships in Bottles: A History of American Maritime Museums (book manuscript in progress).