Couperin Birthday Celebration!

Wednesday, September 26th, 2018

12:00pm – 12:50pm

Paley Library Lecture Hall

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

The opening concert of the 2018-19 Beyond the Notes concert series, features Dr. Joyce Lindorff, Boyer Professor of Keyboard, leading a birthday celebration for François Couperin, marking 350 years since his birth. François Couperin, like Johann Sebastian Bach, was part of a large family of music-makers. For example, Couperin’s uncle was also a noted composer, and his cousin Armand-Louis was especially noted as an organist, but François was sometimes referred to as “Couperin Le Grand” to set him apart from the rest of his family. Recognized as a leading French composer of the 17th century, Couperin’s musical textures have continued to inspire musicians and composers in the centuries since his death. For example, Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin, a solo piano with an orchestral version, is a concert staple, and is likely more familiar to the typical concertgoer than any piece of Couperin himself. Nevertheless, music like the Pièces de Clavecin features a palette that is distinctive, lush, sometimes witty, and sometimes harmonically adventurous.

Couperin is especially known for his music for harpsichord. Unlike its most famous successor the piano, the harpsichord is a keyboard instrument in which the strings are plucked rather than hit. In addition to an altogether different sound quality, a major difference is that when a musician presses a key with more or less force, it will not change the dynamic [volume] of the note as it does on the piano. This means that the composer and performer must control the feel of each section of music without having a direct means to control how loud or soft each note is. Instead, our overall experience of the music will be shaped by other means, such as texture and tempo (speed). The density of writing will shape our experience of the intensity of the music rather than volume.

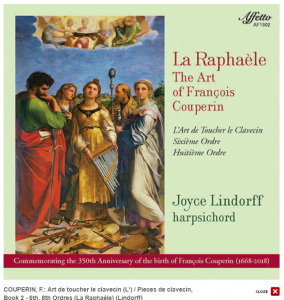

Dr. Joyce Lindorff, professor of keyboard at Boyer, released a CD earlier this year of her performances of Couperin’s L’Art de Toucher le Clavecin. Lindorff’s CD-liner notes offer information about Couperin’s attitude toward pedagogy and performance:

Dr. Joyce Lindorff, professor of keyboard at Boyer, released a CD earlier this year of her performances of Couperin’s L’Art de Toucher le Clavecin. Lindorff’s CD-liner notes offer information about Couperin’s attitude toward pedagogy and performance:

“Couperin is a commanding presence, providing precise fingering for difficult passages in his first book of Pièces de clavecin, keyboard exercises, and a detailed table of ornaments, which he insisted be executed exactly as he wrote them. Rather than trusting players of his unmeasured preludes to interpret the customary minimalist French notation, Couperin instead provides richly detailed templates to be played with freedom. And in marked contrast to modern teaching methods, he advises that young students never practice in the teacher’s absence.”

At that time, music students would have been trained in improvisation far more than now. The level of detail that a composer would notate would be far less, and the musician would be expected to know how to embellish and interpret the music that was written. Rather than playing merely the notes on the page, musicians would add ornaments, or musical flourishes, such as rapid alterations between adjacent notes. In today’s world, with so many styles of classical music in circulation and a lack of a common set of conventions in the music being written by contemporary composers, leaving so much up to the interpretation of the performer may not be practical. However, it is unusual that in the 17th century Couperin would have written out the ornaments that he wanted the players to include.

The extent to which a composer ought to exert influence over performers has been a subject of much debate in recent decades. For example, Christopher Small (1998) sees a hierarchical system of power within orchestral music with the composer at the top. This privileging of the composer allows for a sometimes-oppressive musical canon to emerge, from which composers with less privileged identities, such as most female and non-white composers, would be excluded (Citron 1992). In December, Dr. Lindorff hosted a symposium at the library on such issues, which are becoming an increasingly large part of the historical study of music.

What would this mean in the 17th century? A prevailing view is that the modern idea of the “master composer” is a product of 19th century German Romanticism (Chua 1999). While this may be true, listening to the music of Couperin gives us a chance to see how such issues and differences of opinion would have played out even in earlier centuries. While his attitude suggests an unusual degree of control for his time, when listening to [the CD of] Lindorff’s performance, the listener is struck by the sense of freedom, and often leisure, that manages to prevail. Could the effects of each piece have been achieved with less specificity from the composer? Would that have been better or worse? Dr. Lindorff notes: “the French baroque music has a very paradoxical combination of seeming prescriptive, such as the ornament signs, but also there were extra freedoms, such as the unmeasured preludes and other liberties that could and should be taken.”

For sure, the identity dynamics I mentioned above are also worth considering for Couperin’s time as they are in later centuries: could a female composer at the time provide a table of ornaments and insist her pieces be executed exactly as she notated them, as he did? There is never a simple answer to the question of who gets to control art, but listening to Couperin can invite us to keep asking the question in different ways. Dr. Lindorff offers the following comment: “actually there was one particular female composer at the turn of the 18th century–Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, who was very well received by Louis XIV and influential to other musicians, and whose music was extremely detailed. She was unusual, though.”

To some who have learned a musical instrument, the idea that one must not practice without the teacher present may be hard to fathom. Whether evidence of his desire for control, or perhaps his enormous generosity of time and patience toward his students, it seems that Couperin hoped that his work be played as he intended. No matter the rigidity or flexibility of the composer, Couperin likely did not envision his music being performed in a twenty-first century library lecture hall with a birthday cake in his honor. This performance invites us to experience his music in new and different manners. So start the music! Let the party begin!

References and Further Information:

Denis Arnold & Julie Anne Sadie, “Couperin,” Oxford Companion to Music, Allison Latham, ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Daniel K. L. Chua, Absolute Music and the Construction of Meaning (Cambridge University Press,

1999), 1-28.

“Harpsichord [Fr. clavecin; Ger. Cembalo, Kielflügel, Clavicimbel; It. clavicembalo; Sp. clavicémbalo, clavecín].” The Harvard Dictionary of Music, edited by Don Michael Randel, Harvard University Press, 4th edition, 2003. Credo Reference, Accessed 04 Sep. 2018.

Christopher Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1998), 1-29.

Richard Taruskin, “The Pastness of the Present and the Presence of the Past,” Text & Act: Essays on Music and Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 90-154.

—

Ben Safran is a Ph.D. candidate in music at Temple University, where his dissertation focuses on contemporary classical composers’ uses of social justice and political themes within concert music. His compositions have been performed by various ensembles and musicians across the United States.

One response to “Start the Music! Let the Party Begin!”

Hello, everything is going nicely here and ofcourse every one is sharing information, that’s in fact excellent, keep up writing.