Public History MA student Joana Arruda shares her perspective on a quick stint with the National Park Service.

From March 9-13, I participated in a Park Break program along with seven other graduate students from various corners of the country. Sponsored by the George Wright Forum and the National Park Service (NPS), Park Break is an annual program that selects graduate students from all disciplines to work on projects at one natural and one cultural-based park. This year, Philadelphia’s own Independence National Historical Park was chosen as one of the sites.

The staff at Independence asked Park Break students to create an exhibit for New Hall, a building located between 3rd and 4th Streets on Chestnut Streets. New Hall was built in 1791 and served as the War Department and the office of the nation’s first Secretary of War Henry Knox. Until recently, the building served as a military museum, but the staff hoped to incorporate the archaeological artifacts found there in the 1950s in a new exhibit. Additionally, they asked that we develop a digital exhibit to showcase our findings. With only five days at Independence, our work was cut out for us.

Upon arrival, we toured New Hall and immediately began research in the Park’s Archives. We found evidence that after the War Department left Philadelphia for Washington, D.C. in 1800, New Hall had a variety of civilian uses throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For example, an architecture school was housed on the third floor of New Hall, which produced student John McArthur, Jr., architect of Philadelphia’s City Hall. We realized that New Hall had more important links to the city than we had realized.

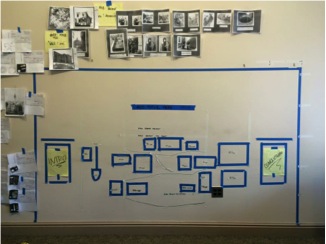

At this point, our team began thinking about how to visually organize our exhibit as well as the narrative that would tie it all together. New Hall continues to operate as a military museum, and we wanted to be conscious of the types of audiences that would come through. After much discussion, we decided to visually create an exhibit that recreated a timeline. However, we wanted to refrain from using vertical or horizontal timelines not because only because they could be tedious, but they because would not represent as well the simultaneity of events. What we came up with was to reconstruct the stratigraphic layers from the archaeological record. Each drawn layer would show the artifacts found there, and these artifacts would be laid out in several cases.

The archaeological record until 1900 was surprisingly complete, but we had no such materials following this period. We chose to represent the twentieth century with photographs from the Archives. Throughout the process, we split up into several groups to work on different areas of the project that best suited our strengths. The students trained in landscape architecture, museology, and architecture worked on the visual display.

Myself and another public history student banded together to write the historical narrative and the text panels that would hang at the exhibit. We wanted to focus on the building’s significance on several levels. We did so by incorporating the history of the building in its own right, as well as its connections to local Philadelphia history and the larger national story. Our narrative also placed New Hall within the context of the entire park. Two other students focused on the military’s contribution to the history of New Hall, and connected it to the issues of the modern-day military-industrial complex, much of which has its origins with the War Department of the 1790s. This overall work was also developed to appear in a digital exhibit on a phone app.

On Friday morning, we presented our exhibit proposal to the staff team, including the curator, archaeologist, and various other members at Independence. We had met many of them throughout the week, some of who discussed their careers with the National Park Service. Our team outlined our proposal to the Independence team, and the staff had high praise about the extensive work we had completed in just a few days. The group, along with the staff, had a larger conversation about audience expectations, the narrative we had created, and the use of archaeology to spark interest in New Hall.

As a public history graduate student, I’m often exposed to conversations about interdisciplinary collaboration, but I’ve found this to be a rare find in some projects. However, Park Break was a great way to put this challenge to the test in an idealized setting. While I was comfortable being a voice for the historical process in the project, I was also thrust out of my comfort zone when I had to learn quickly how to understand the perspective of others in the group who thought of things that had never occurred to me about spatial design or visitor patterns. It was a great experience for me to think about public projects from the perspective of those outside of the field.

This experience gave me the opportunity to understand the face of public history in a large institution like that of the NPS. It will be interesting to see how the NPS implements our exhibit proposal into a physical exhibit in the coming year.

Creating an exhibit with virtually no restrictions was a liberating way to do history. The NPS, of course, has limits that it must adhere to, but I think we created a useful product that enhances what the park aims to do for its visitors.