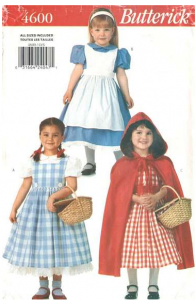

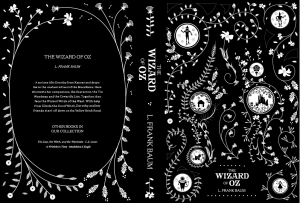

Last semester, I had to design covers for a series of books that had been banned in America. They didn’t have to be new releases, or recently banned, and they could have been banned for any reason. After several hours of preliminary research, I discovered that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz had been banned in America because it contained references to magic. I researched The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, eager to learn more. The pull-quote that I wanted to use on the back of the dust jacket- “I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” was nowhere to be found. I soon realized that the book itself was quite different from the movie. The most famous quote, and, I would argue, the longest lasting cultural reference from The Wizard of Oz, was not written by L. Frank Baum at all. It was written by an MGM screenwriter.[1] The other cultural relic, “There’s no place like home,” is a direct reference to this quote:

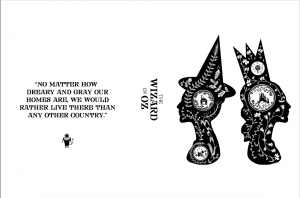

“No matter how dreary and gray our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather live there any in any other country, be it every so beautiful. There is no place like home.”[2]

However, this quote has a very different feel to it than the incantation which takes Movie Dorothy home. Instead of a simple, wistful wish, the book version of Dorothy disparages “home” as boring, dreary, gray, and sad.

“We’re not in Kansas anymore,” is a rather flippant quote when compared to the book’s many quotes about perseverance, grit, teamwork, regret, fear, etc. It has become an American icon unto itself. There are books which rely on this quote for their titles, TV shows which utilize it in dialogue or episode names, and movies which reference it in conversations between characters. Other reference-types include newspaper articles, songs and albums, video games, anime and comic books.[3]

| Movie |

The Matrix

Cypher |

Avatar

Colonel Quaritch |

Little Shop of Horrors:

Audrey / Audrey II |

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

Amy / Nick |

| TV Show |

Dukes of Hazzard |

Power Rangers |

MythBusters |

90210 |

| Song |

Big Country- We’re Not In Kansas |

Mystery Train- Bon Jovi |

The Farm- Aerosmith |

305 to My City- Drake, Detail |

The allegory of the Populist movement as described and discussed by Henry M. Littlefield is compelling and interesting interpretation.[4] I think most Americans have not read the book, and most of those who have are not historians. This meaning might have been very important and visible in 1900 when the book was released, but I think it is lost on most people now. The movie is the biggest cultural reference, and has changed many of the key elements of the book which Littlefield’s interpretation relies upon.

Roger Ebert’s movie review of The Wizard of Oz references the movie’s emphasis on bumbling adults who are either not paying attention to children, or are too inept to help them. Ebert’s interpretation is that the basis for the movie’s appeal is the pluckiness of children, the anxiety of not being taken care of and the personal growth of realizing you can take care of yourself. Children can relate to this story arc, and grownups can look fondly back on their own life and revisit their childhood.[5] Littlefield’s interpretation is different; that the Wizard of Oz does not represent grownups, he represents the government. It is a far less comforting message to consider that the government is inept, careless, and distracted.[6] I believe that this interpretation is especially important now. During the 2016 election cycle, both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump ran on the platform that “business as usual,” was not working. Hilary Clinton, a woman who has been deeply involved in politics for decades, was distrusted because of her political involvement.[7] Learning about Littlefield’s interpretation from Rainie’s presentation and class discussion, I couldn’t help but to notice the similarities between the turn of the nineteenth century sentiment and now. The distrust of immigration, the anger at the government, as well as the swaths of America which felt left behind, all seem to be contemporary issues. There are no easy answers now, as there were none then. I believe it is important to reevaluate Henry M. Littlefield’s interpretation of the book. As an icon, it can do more good than the movie.

As an aside: I found this strange wedding planning blog that says most brides’ favorite movie is the Wizard of Oz, so a bride planning her wedding should consider poppies for her floral arrangements. Pretty weird since all the characters almost die in the poppy field.

http://www.weddingwindow.com/blog/oh-poppies/

Works Cited

Shmoop Editorial Team. “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Home Quotes Page 1.” Shmoop. November 11, 2008. Accessed March 01, 2018. https://www.shmoop.com/wonderful-wizard-of-oz-book/home-quotes.html.

Ebert, Roger. “The Wizard of Oz Movie Review (1939) | Roger Ebert.” RogerEbert.com. December 22, 1996. Accessed March 01, 2018. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-the-wizard-of-oz-1939.

Houlberg, Lauren. “Writing Resources.” The Wizard of Oz: More Than Just a Children’s Story by Lauren Houlberg. Accessed March 01, 2018. https://wr.english.fsu.edu/College-Composition/Our-Own-Words-The-James-M.-McCrimmon-Award/Our-Own-Words-2005-2006-Edition/The-Wizard-of-Oz-More-Than-Just-a-Children-s-Story-by-Lauren-Houlberg.

Leonhardt, David. “Why 2016 Is Different From All Other Recent Elections.” The New York Times. January 19, 2016. Accessed March 01, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/19/upshot/why-2016-is-different-from-all-other-recent-elections.html.

Nix, Elizabeth. “8 Things You May Not Know About “The Wizard of Oz”.” History.com. May 26, 2015. Accessed March 01, 2018. http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-wizard-of-oz.

“Not in Kansas Anymore.” TV Tropes. Accessed March 01, 2018. http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/NotInKansasAnymore.

[1] Elizabeth Nix, “8 Things You May Not Know About “The Wizard of Oz”.” History.com.

[2] Shmoop Editorial Team. “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Home Quotes Page 1.” Shmoop.

[3] “Not in Kansas Anymore.” TV Tropes.

[4] Lauren Houlberg. “Writing Resources.” The Wizard of Oz: More Than Just a Children’s Story

[5] Ebert, Roger. “The Wizard of Oz Movie Review (1939). Roger Ebert.

[6] Lauren Houlberg. “Writing Resources.” The Wizard of Oz: More Than Just a Children’s Story

[7] David Leonhardt. “Why 2016 Is Different From All Other Recent Elections.” The New York Times.