Social norms of history have placed women within the box of a wife and home giver. In the historical mindset that is her place. These norms are an interesting issue for those women who desire to make some form of social change. Even if their interests are not simply the expansion of these norms they still face the repercussions of them. Strong People and Strong Leaders and Rethinking Betty Friedan tackle the role that some women choose to portray, while others are forced into. Strong People and Strong Leaders comments on the inability of African Americans to be taken seriously in the civil rights movement. Rethinking Betty Friedan makes a similar statement. This article breaks down that while Betty Friedan had a strong background in civic leadership she portrays herself as a housewife to appeal to a greater audience. She felt that being a housewife would make her more accessible to the women audience she desired.

The description, “Men lead, and women organized” would sum up the leadership hierarchy of the civil rights movement. Women found themselves corned with the fact that the SCLC was strongly minister driven. They claimed that the autocratic leadership style did not empower people but actually limited their ability to act. The strict hierarchical system limited the power of the ordinary man. Women were unable to speak during event marches and were generally snubbed from direct leadership positions. Many leaders of the civil rights movement felt that if women were given such positions then the organization would not be viewed with the gravity they desired. This puts black women in a difficult position. They are not allowed to participate in women’s rights organizations like the National Women’s party or their events because of their race. While civil rights organizations like the SCLC wouldn’t allow women to take direct leadership positions because of their gender. Black women are but at this particularly disadvantageous position within society.

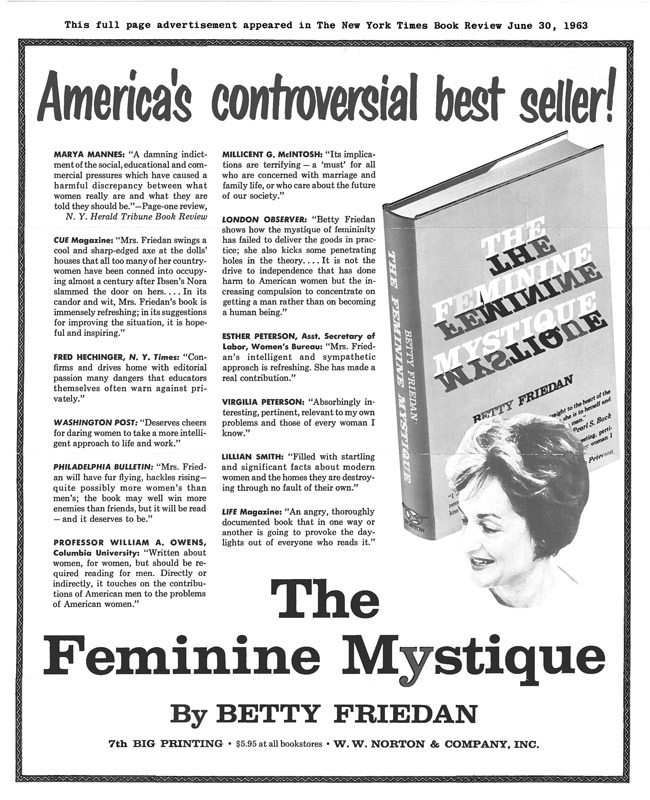

While some woman struggled against the norms forced upon them, women like Betty Friedan used society’s view to reach their audience. Betty Friedan was labor activist who organized the building and grounds team into

a union. She worked for the Federated Press a left-wing news periodical that wrote mostly to labor unions. But in her own narrative, she claims that it was pressure by her first serious boyfriend to turn down a substantial fellowship at Berkeley. She also claims that she ended up as an old maid teacher. These stories she portrayed are at least partially fictitious. We know today that Friedan was much more than what she portrays herself to be. She plays up the domestic nature of her life while living out the political passion for labor writing. She used the ideas of what society viewed she should be, as a way to appeal to a larger audience. Readers like people who they feel can relate to them. Betty Friedan used this to her advantage and created a life narrative accordingly.

a union. She worked for the Federated Press a left-wing news periodical that wrote mostly to labor unions. But in her own narrative, she claims that it was pressure by her first serious boyfriend to turn down a substantial fellowship at Berkeley. She also claims that she ended up as an old maid teacher. These stories she portrayed are at least partially fictitious. We know today that Friedan was much more than what she portrays herself to be. She plays up the domestic nature of her life while living out the political passion for labor writing. She used the ideas of what society viewed she should be, as a way to appeal to a larger audience. Readers like people who they feel can relate to them. Betty Friedan used this to her advantage and created a life narrative accordingly.

[6]

[6]