A revised version of this essay was published in Chesapeake Bay Magazine on June 5, 2025, and can be seen here: https://www.chesapeakebaymagazine.com/a-50-foot-oyster-shell-the-bay-bridge-watermens-monument-that-almost-was/.

Watermen monuments were all the rage in Chesapeake Bay communities during the 1990s. In places like Rock Hall, Grasonville, and Solomons Island, locals raised money to commemorate men who worked and sometimes died on the water. It was a time when Maryland’s blue crab fishery, like the oyster fishery before it, had suffered precipitous declines. The ubiquity of those monuments in travel brochures and tourist itineraries—even to this day—shows how fully people invested in public memory as a hedge against Maryland’s fickle maritime economy.[i]

It was not the first time, though, that Marylanders turned to heritage tourism amid contractions in the fisheries. Beginning in the 1930s, prompted by global economic recession and slumping seafood harvests, boosters pitched the Eastern Shore’s historical charms relentlessly to auto tourists and real estate investors. The Baltimore Sun instructed travelers on how to see “The Sho’ Through a Windshield.” Real estate agents hawked old plantation homes to wealthy investors from New York City. And A. Aubrey Bodine’s distinctive photojournalism reimagined working watermen not as industrial laborers, but as picturesque guardians of a bygone era, men who were “in our time but not of it.” By the time the Chesapeake Bay Bridge opened in 1952, these were the rustic enticements that lured wealthy people east and that fixed the Eastern Shore on its path to becoming a weekend getaway for the well-heeled.[ii]

Looking back now it is easy to see how those 1990s watermen monuments commemorate a usable past dreamed up a generation earlier by people eager to solve their own economic problems.

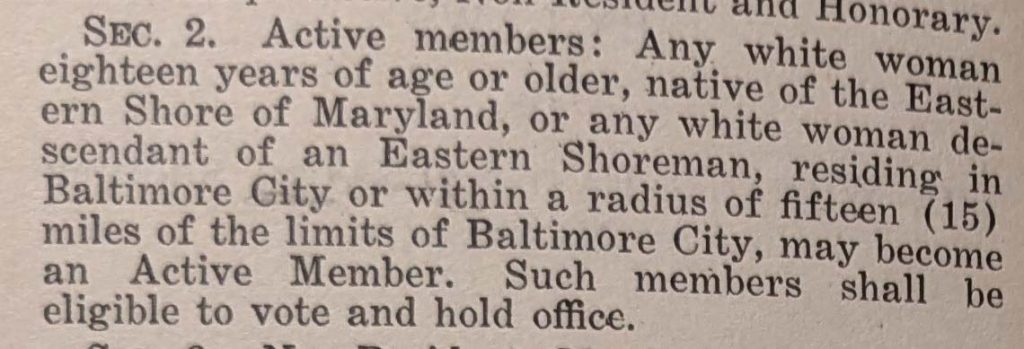

But even back then there were disagreements over how to remember. Consider the proposal, floated in 1951, to erect a fifty-foot-tall monument at the eastbound entrance to the soon-to-be-completed Bay Bridge. A plaster mockup of the monument garnered considerable attention at the Maryland Conservation Federation’s Flower and Garden show held that year in Baltimore’s Fifth Regiment Armory Building. It depicted an aged watermen sitting with his grandson, gesturing wistfully toward the bay. Behind them rose up a massive oyster shell inscribed with the words: “as ye sow ye shall reap” [see image above].[iii]

Unlike the Eastern Shore tourism campaign, which romanticized Maryland’s historic fisheries, the proposed waterman monument was more like a rap on the knuckles. The Federation intended it to remind passersby that the environmental damage done by unfettered oyster harvesting was a choice and that they could, in fact, choose otherwise. Federation president H. Lee Hoffman explained that “the purpose of the new monument will be to remind Marylanders [that the Bay] still has great resources potential for the commercial fisherman and recreational use as well.” An opinion writer for the Sun put it in sharper terms: “The bay oyster beds have been dredged to extinction … can any loyal Marylander callously neglect the memory of its most succulent aborigine?”[iv]

Thus was thrown yet another jab in what by then had been a decades-long fight over what to do about declines in Maryland oyster harvests. States including Rhode Island and Connecticut had already turned to the artificial cultivation techniques advocated for by conservationists concerned to rebuild depleted oyster beds. In Maryland, however, where prior to the 1960s tidewater communities enjoyed enormous power in the state legislature, watermen leveraged all of their political capital to defy the conservationists. What could science tell them about oysters that they didn’t already know? And why listen to conservationists who, the oystermen insisted, were just corporate hacks looking to privatize the bay?[v]

It wasn’t politics, though, that defeated the Federation’s goal of pitching oyster conservation directly to bridge commuters. The bigger problem was that, well, the monument was just plain ugly. Hans Schuler, longtime director of the Maryland Institute College of Art, designed it himself, going so far as to interview “a number of watermen before completing his search for one who would be typical of the trade and … suitable to pose for the [statue].” But even despite Schuler’s efforts, many visitors to the Flower and Garden Show agreed with Lee Lawrie of Easton that there “should be a better monument” to go along with the Federation’s plan. Mrs. Gay of Baltimore thought “the oyster shell is terrible.” E.J. Marhsall of Westminster agreed: “the statue is hideous.”[vi]

Needless to say, the monument campaign never quite hit its mark. Erstwhile Federation president Hoffman was still making the case five years later, hopeful that another organization might adopt the mockup so that he would no longer have to keep it in storage. In a letter to the Maryland Board of Natural Resources, Hoffman predicated that the monument would draw visitors in “large numbers” just as had Massachusetts’s 1925 Gloucester Fisherman’s Memorial. But if a taker could not be found, Hoffman continued, then the outsized shell should be thrown in the bay “where oysters will soon find it an excellent deposit for their spat, thereby helping in a small way to restore oyster production.”[vii]

Whatever actually became of Hoffman’s shell is unclear. What is clear, though, is that monuments have always been poor conduits for complicated ideas. Selling conservation means making delicate arguments about marine biology, regional economics, and environmental sustainability. It is a conversation too about labor, identity, and cultural heritage. The sculptural confluence of these themes ended up being too confusing, and so Schuler tried to make it work by putting the oyster first. His is an angry oyster, large and looming, bent on biblical admonition. Is it any wonder that Marylanders balked?

Conversely, the watermen monuments that did eventually get made always put the watermen first. As if plucked straight from a Bodine photospread, they focus squarely on manhood, heroism, and the virtues of working hard on the water. But here too are problems. You’d never know from the watermen monuments we have today that there ever was—or still is—an argument about oyster conservation. You’d never know that Marylanders who work on the water have always been more diverse and never quite so rustic as the statues would have us believe. You’d never know, that is, that there are other ways to remember. In the end, what we learn by remembering Maryland’s forgotten 1951 watermen’s monument is that monuments never were going to fix the tidewater’s economic problems. Doing that means finding ways to have the hard conversations about history, power, and the environment for which monuments are always a poor substitute.

[i] See, for instance, Michaila Shahan, “30th Anniversary of Watermen’s Memorial,” CBM Bay Weekly (May 19, 2022), https://bayweekly.com/solomons-marks-30th-anniversary-of-watermens-memorial/; Doug Bishop, “Md. Watermen’s Monument rededicated; challenges facing industry discussed,” MyEasternShoreMD (November 6, 2013), https://www.myeasternshoremd.com/news/queen_annes_county/md-watermens-monument-rededicated-challenges-facing-industry-discussed/article_089f459d-a352-589d-b4ec-482e91210ff5.html; and “Rock Hall’s Beloved “Old Salt” Statue Restored,” Chesapeake Bay Magazine (July 11, 2023), https://www.chesapeakebaymagazine.com/rock-halls-beloved-old-salt-statue-restored/.

[ii] Gerald Griffin, “The Sho’ Through a Windshield,” The Baltimore Sun (May 13, 1934). On the sale of the colonial Blakeford mansion, for instance, see “Old Estate on Eastern Shore Purchased By New York Man,” The Baltimore Sun (November 22, 1934). The quote is from Franky Henry, “Elliott Island: In Our Time but Not of it,” The Baltimore Sun (March 28, 1954).

[iii] Photographs of the monument, including the one pictured, are from folder “Envelope 2 flower show 1957,” Box 1, Hoffman-Maryland Conservation Federation Photograph Collection (PP49), Special Collections, Maryland Center for History and Culture.

[iv] H. Lee Hoffman, “Proposed Chesapeake Bay Resources Monument,” in folder “1950-51 Subject Files-Chesapeake Bay Resources Monument,” Box 3, Harry Lee Hoffman, Jr. Collection (MS 2583), Special Collections, Maryland Center for History and Culture. “A First Step Toward a Fitting Oyster Memorial,” The Baltimore Sun (February 9, 1951).

[v] Christine Keiner, The Oyster Question: Scientists, Watermen, and the Maryland Chesapeake Bay since 1880 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009).

[vi] Deborah B. Morrison, “An Old Watermen Visits the Flower Show,” The Baltimore Sun Friday Morning (March 2, 1951). A list of responses appears in in folder “1950-51 Subject Files-Chesapeake Bay Resources Monument,” Box 3, Harry Lee Hoffman, Jr. Collection (MS 2583), Special Collections, Maryland Center for History and Culture.

[vii] Hoffman to William Bayliff, secretary of the Maryland Board of Natural Resources, August 9, 1956, in folder “1951-58 Correspondence,” Box 2, Harry Lee Hoffman, Jr. Collection (MS 2583), Special Collections, Maryland Center for History and Culture.