Beyond the Notes presents

Exploring Beethoven’s Scottish Folk Song Arrangements—

Demystifying an Enigma

Wednesday, March 27, 2024, 12:00 PM

Charles Library Event Space

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged.

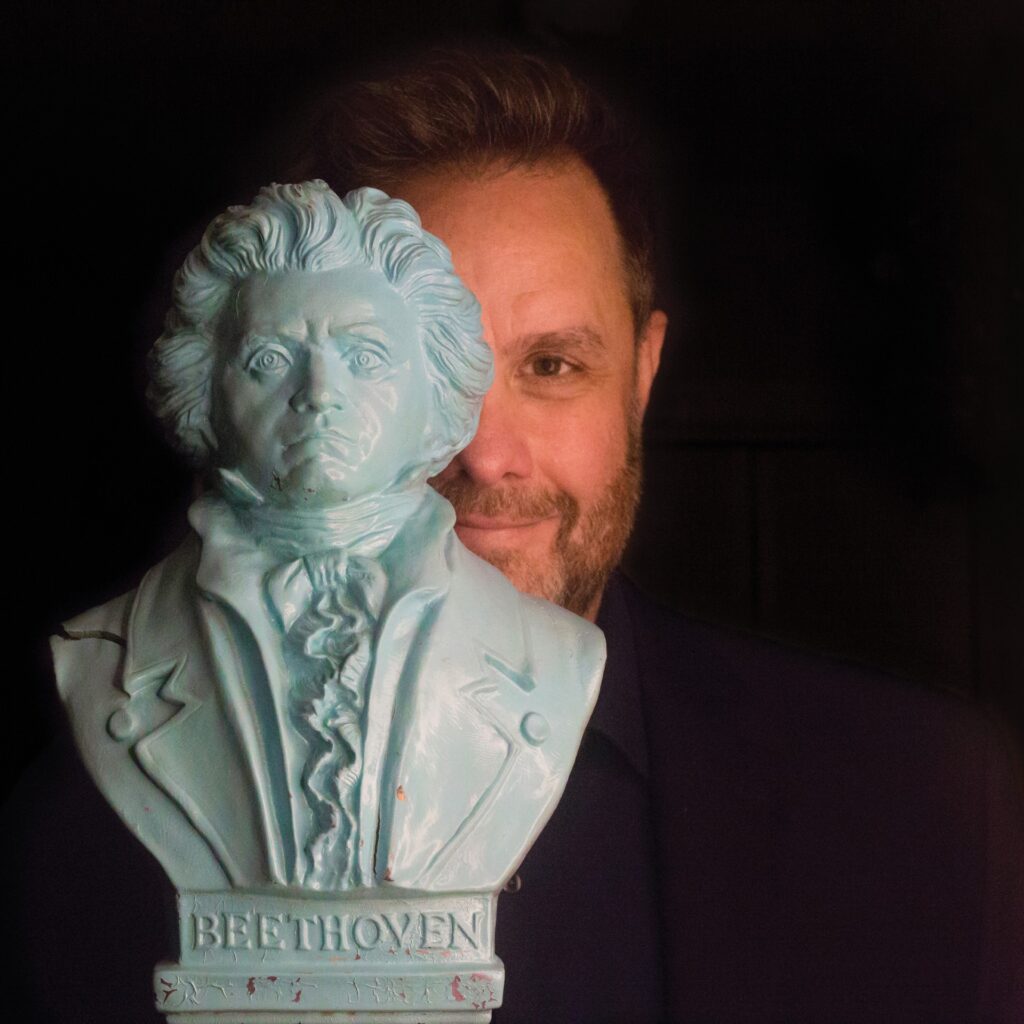

Our final Beyond the Notes concert of the 2023–2024 season features a curious sampling of Ludwig van Beethoven’s repertoire: arrangements of Scottish folk songs for voice and piano trio written between 1809 and 1819. During this performance, baritone Daniel Neer will ask us to consider what led Beethoven, already a Big Deal by 1809, to compose these works, along with settings of other British and Irish folk songs and poetry. Such works might seem an odd choice for the man who had already written six symphonies, all but his final piano concerti, his Violin Concerto, and his Choral Fantasy, not to mention more than two dozen piano sonatas and other major works of chamber music. But Beethoven would hardly be alone for apparently having developed a fascination with so-called Celtic music. From before Beethoven’s time to the present, composers, musicians, and especially audiences have been fascinated with music that has come to be called generically “Celtic.” But what is “Celtic music” anyway?

Scott Reiss asks this same question in his work on Irish traditional music: “Is it the traditional music of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, and other nations that share the heritage of the ancient Celts? Or is it something separate, that might be understood as interacting with those traditional musics and the communities that produced them?”1 The label “Celtic,” he points out, is rightly criticized for “eras[ing] the boundaries between Irish, Scottish, Welsh, and Breton traditional musics,” allowing commercial forces to market all traditional musics and other cultural artifacts and activities from the Celtic world to a broader audience hungry for all things “Celtic.”2 Late 20th- and early 21st-century music groups as diverse as the Chieftains, Clannad and Enya, the Pogues, the Cranberries, Sinéad O’Connor, Riverdance and Michael Flatly, The Irish Tenors, and of course Celtic Woman have profited (intentionally or not) from the popularity of Celtic music. Similarly, Celtic-influenced film soundtracks such as the Chieftans’s soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), Trevor Jones’s use of Dougie MacLean’s Scottish fiddle tune “The Gael” in The Last of the Mohicans (1992), James Horner’s Enya-influenced score for Titanic (1997), and Mychael and Jeff Danna’s “The Blood of Cu Chulainn,” which appeared on their album “A Celtic Romance” before it became the hit theme song from the gritty crime thriller The Boondock Saints (1999), have further contributed to and fueled the fires of Celtic mania.

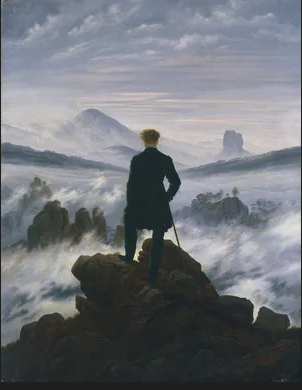

Classical composers since before Beethoven have found inspiration in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and England—not only in their music, but often in their rugged and sublime landscapes as well. Felix Mendelssohn’s oeuvre includes two works apparently inspired by his travels to Scotland: The Hebrides Overture (subtitled “Fingal’s Cave”) and his “Scottish” Symphony no. 3. In 1829 when he was only 20 years old and already developing his reputation across Europe, young Felix and his friend Karl Klingemann set off on a walking tour of Scotland, during which time Felix encountered bagpipers, visited with Sir Walter Scott, sketched landscapes of the rugged Scottish highlands, and found the inspiration for his Hebrides Overture looking out onto the eponymous islands off the west coast of Scotland.

Nowadays we take Mendelssohn’s fascination with Scotland and its influence on his work for granted, but two anecdotes cast doubt on this “common knowledge.” First is the fact that the so-called “Scottish” Symphony was not known by that title until after Mendelssohn’s death, after which time the moniker stuck and was accepted without question. Despite later anecdotes by various friends and family members insisting that the 1829 trip to Scotland, and particularly his visit to Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, had inspired the piece that he completed 13 years later, there is, as Thomas Schmidt-Beste argues, “little or no evidence that Mendelssohn himself, by the time he had actually finished the piece, thought of his symphony as ‘Scottish’ in the sense of a piece ‘about’ Scotland.”3 Rather, the evidence suggests that while he did sketch out early ideas for the piece on the day of his visit to Holyrood and early writings about the piece distinguish it from the “Italian” Symphony (which would eventually become his fourth) by referring to it as “Scottish,” by the mid-1830s he had dropped that title and referred to it only as the “symphony in A minor.” His eventual dedication of the piece to Queen Victoria clarifies the work’s connection to Scotland:

Thus, it was my desire to present that piece to Your Majesty which had been the reason for my last visit to England, and His Royal Highness Prince Albert had the good grace to give permission in the name of Your Majesty. The Symphony is enclosed; may Your Majesty accept it graciously and kindly! It belongs to Your Majesty in every respect, since the first idea for it came about during my earlier journey through Scotland, and since it brought me the pleasure after its completion to accompany Your Majesty singing my own songs.”

Mendelssohn’s dedication of his Third Symphony to Queen Victoria, quoted by Thomas Schmidt-Beste4

While it feels safe to say that the “Scottish” Symphony (now the scare quotes seem all the more apt) is not really about Scotland even if it was almost certainly inspired by Scotland, we can be confident that Mendelssohn was thinking about the Hebrides, and specifically about Fingal’s Cave and perhaps even the 18th-century epic poem chronicling the eponymous hero Finn McCool, when he wrote The Hebrides Overture. It might, therefore, surprise us that around this same time, he wrote a letter home to his family laying out in no uncertain terms his distaste for Scotland’s folk musics:

“No national music for me! Ten thousand devils take all folkishness! … [A] harper sits in the hall of every reputed inn playing incessantly so-called folk melodies; that is infamous, vulgar, out-of tune trash, with a hurdy-gurdy going on at the same time! It drives one to distraction, and has unfortunately given me a toothache. Scottish bagpipes, Swiss cow-horns, Welsh harps, all playing the huntsman’s chorus with hideously improvised variations … It is beyond conception! Anyone who, like myself, cannot endure Beethoven’s national songs, should come here and listen to them bellowed out by rough, nasal voices, and accompanied with awkward bungling fingers, and not grumble.”

Letter dated August 25, 1829, quoted by Matthew Gelbart5

These are surprising words not only from a composer apparently entranced by Scotland’s beauty, but also from a young Romantic immersed in the contemporary Zeitgeist that prized idealized notions of the “folk” and nationalism, which were so often encapsulated by the idea of folk song.6 But musicologist Matthew Gelbart, who quoted this letter in his article “Once More to Mendelssohn’s Scotland,” urges us not to take Mendelssohn’s dismissal of folk music too seriously, reminding us that earlier, Felix had written to Klingemann of his eagerness to experience Scotland’s “folk melodies, [with] an ear for the lovely, fragrant countryside…,” and his frequent mentions of an interest in bagpipes.7 Perhaps these were the words of a cranky 20-year-old who had been away from home too long and had heard some particularly poor performances in the many inns and taverns he had been traveling through, rather than a reflection of his true feelings. But it is noteworthy that unlike Beethoven, who set actual folk songs and poetry to music, Mendelssohn seems to have been inspired more by the Scottish landscapes he encountered, “the lovely, fragrant countryside,” than by the tunes he heard.

We hope you enjoy Beethoven’s Scottish songs and that you will seek out more music inspired by Scotland and the Celtic world!

Interested in additional classical repertoire inspired by Scotland and the Celtic world? Check out these pieces:

- Amy Beach, Gaelic Symphony op. 32, E minor (1897)—find the score here

- Franz Joseph Haydn, arrangements of Sottish, Welsh, and Irish folk songs—find two of these songs here

- Peter Maxwell Davies, Farewell to Stromness (1980)—find an arrangement for guitar here

- Gaetano Donizetti, Lucia di Lammermoor (1935)—final the vocal score here

- Thomas Moore, Irish Melodies (published between 1808 and 1834)—find the score here

- Max Bruch, Scottish Fantasy opus 46 (1880)—find the arrangement for violin and piano here

- Benjamin Britten, Irish Reel (1936, rev. 1937)—find the score here

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, Ca’ the Yowes for Tenor Solo and Chorus of Mixed Voices (1922)—find the score here

- Percy Grainger, Irish Tune from County Derry (1902)—find the score here

- John Corigliano, Three Irish Folksong Settings (1988)—find the score here

- David Popper, Scottish Fantasy opus 71 (1900)—find the arrangement for piano and violin here

- Giuseppe Verdi, Macbeth: opera in four acts (1847)—find the vocal score here

- Scott Reis, “Tradition and Imaginary: Irish Traditional Music and the Celtic Phenomenon,” in Celtic Modern: Music at the Global Fringe (Blue Ridge Summit: Scarecrow Press, Incorporated, 2003). ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Thomas Schmidt-Beste, “Just how ‘Scottish’ is the ‘Scottish’ Symphony? Thoughts on Form and Poetic Content in Mendelssohn’s Opus 56,” in The Mendelssohns: Their Music in History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 155. ↩︎

- Ibid., 156. ↩︎

- Matthew Gelbart, “Once More to Mendelssohn’s Scotland: The Laws of Music, the Double Tonic, and the Sublimation of Modality,” 19th Century Music 37, no. 1 (2013): 3–36, https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2013.37.1.3. ↩︎

- See Harry White and Michael Murphy, eds., Musical Constructions of Nationalism : Essays on the History and Ideology of European Musical Culture 1800-1945 (Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2001); Timothy Baycroft, Folklore and Nationalism in Europe During the Long Nineteenth Century. (Boston: Brill, 2012); and Adrian Daub, What the Ballad Knows : The Ballad Genre, Memory Culture, and German Nationalism (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2022). ↩︎

- Gelbart 5. ↩︎