-

Musings on Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and “Celtic Music”

Beyond the Notes presents Exploring Beethoven’s Scottish Folk Song Arrangements—Demystifying an Enigma Wednesday, March 27, 2024, 12:00 PM Charles Library Event Space Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given. All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. Our final Beyond the Notes concert of the 2023–2024 season features a curious sampling…

-

The Timeless Resonance of the Cello

Beyond the Notes presents Unaccompanied Cello from Bach to the Grateful Dead Wednesday, February 21, 2024, 12:00 PM Charles Library Event Space Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given. All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. The cello, with its rich and varied timbre, has captivated audiences for centuries. Originating…

-

Beyond the Notes: A Visual Music Sampler

Beyond the Notes presents A Visual Music Sampler Wednesday, January 31, 2024, 12:00 PM Charles Library Event Space Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given. All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. Join Boyer Professor of Music and composer Maurice Wright in a presentation of electronic music, live performance, and…

-

From “Fortunate Son” to “The Ballad of the Green Berets”: The Vietnam War in Song

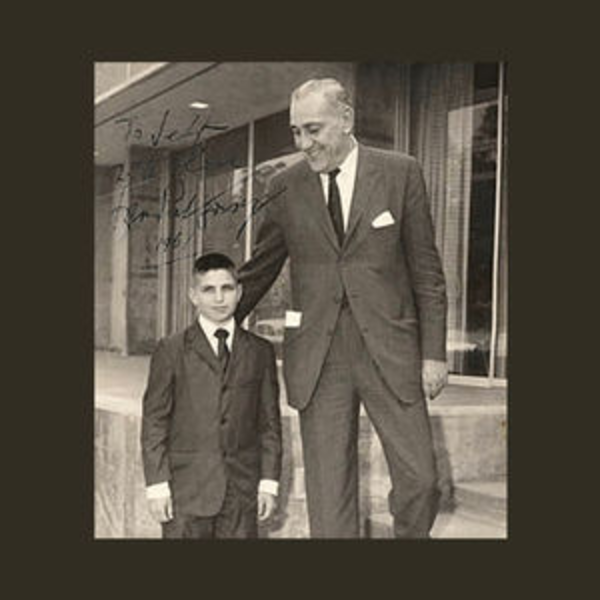

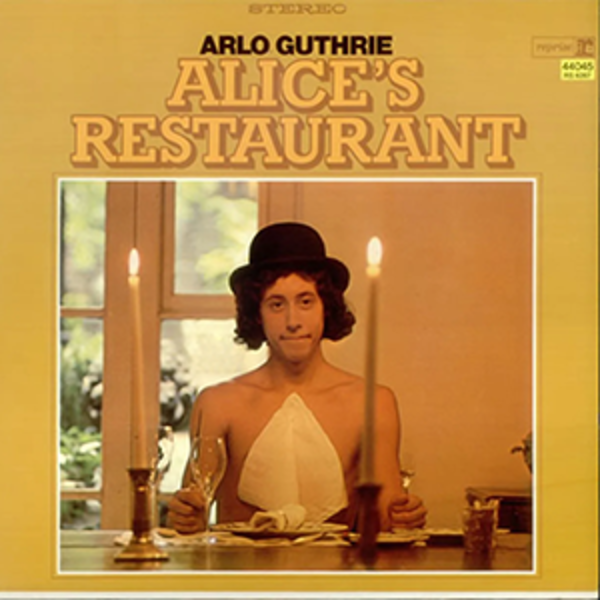

Temple University Libraries presents “Can You Get Anything You Want? The Complicated Story of ‘Alice’s Restaurant’“ A Conversation, Performance, and Singalong Tuesday, November 14, 2023, 3:30 PM Charles Library Event Space Light refreshments served. All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. The Vietnam War was a tumultuous period in American…

-

Beyond the Notes: Folio + Phantasma featuring Relâche Ensemble

Beyond the Notes presents Folio + Phantasma featuring Relâche Ensemble Tuesday, November 7, 2023, 12:00 PM Charles Library Event Space Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given. All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. In recognition of National Epilepsy Awareness Month, Beyond the Notes presents a performance by Relâche Ensemble…

-

Phillis Wheatley: The First Published African-American Poet

Beyond the Notes presents Songs of the People: A Celebration of Women Composers from the African Diaspora Wednesday, April 19, 2023, 12:00 PM Charles Library Event Space Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given. All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Sally Hemings…these names of famous…

-

An Interview with Composer Ashley Reneé Seward.

Beyond the Notes presents Women Composers of Song from Around the World Presented by A Modern Reveal Wednesday, March 15, 2022, 12:00 PM Charles Library Event Space Featuring Boyer College of Music vocal studies students and collaborative pianist Gabriel Rebolla Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given. All programs are free and open to all,…

-

Notes on Playing Slaves: James Ijames and the Legacy of Blackface Minstrelsy

Beyond the Page presents Chat in the Stacks: A Conversation with Temple Alum and Pulitzer Prize Winning Playwright James Ijames All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. PLEASE NOTE THIS CHANGE IN FORMAT: This program was prerecorded and available to view here: https://library.temple.edu/watchpastprograms/show?id=05e0e010-803b-48fd-9121-afb200ea1983 James Ijames (rhymes with “Grimes”), the Philadelphia-based…

-

“The pupil Beethoven was here!”: Salieri’s Other Adversary

Beyond the Notes presentsBeethoven in Vienna Wednesday, February 8, 2023, 12:00 PMCharles Library Event Space Performers: Mădălina-Claudia Dănila, piano Sendi Vartanova, violin Taiysia Losmakova, violin Program: Sonata for piano op. 2 no. 1 in F minor (1795):dedicated to Joseph Haydn Sonata for piano and violin op.12 no. 3 in E flat major (1798):dedicated to Antonio…

-

Remembering Holocaust Survivor Composer Herbert Zipper

Beyond the Notes presentsThe Final Waltz Wednesday, November 9, 2022, 12:00 PMCharles Library Event Space Performers:Daniel Neer, baritoneMarta Zaliznyak ’21, sopranoAriana Grace ’24, sopranoGabriel Rebolla, piano Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged. In remembrance of the 84th anniversary of Kristallnacht–“the night of broken glass” when…