My ongoing search for archival materials on Philadelphia’s urban Indian population has not been easy. Though I have been making progress in identifying collections that will be helpful to my research, it has become evident that archives in Philadelphia leave little evidence of an American Indian presence in the 20th century. Other than the records of the United American Indians of the Delaware Valley, which are housed at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, most archives do not have any collections that specifically document the lives of urban Indians.

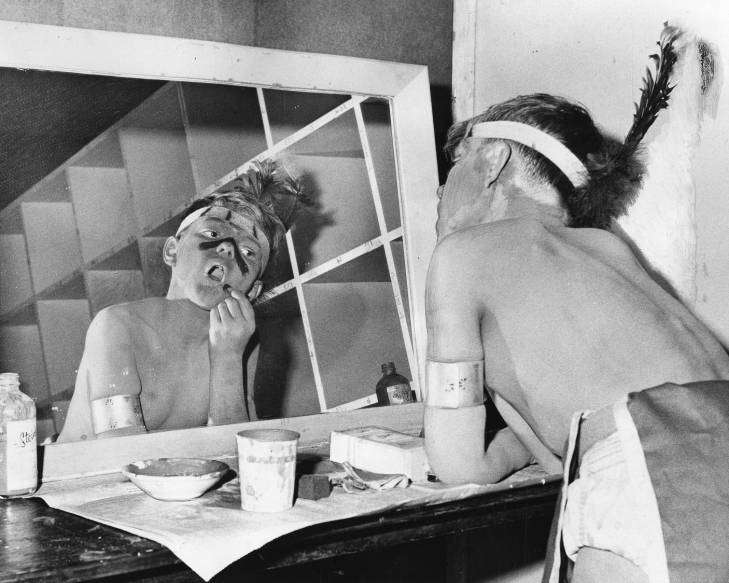

The Special Collections Resource Center at Temple University is known for its Urban Archives, a robust collection of materials documenting Philadelphia’s history from the mid-19th century to present. For fun, I searched for photos with the subject term “Lumbee” in Temple’s digital collections database. No results. Next, I broadened my search terms to “Native American” and “American Indian.” Dozens of results appeared. However, none of the images provided me with any documentation of Philadelphia’s urban Indian community. Instead I was reminded of Philadelphia’s obsession with race and, “playing Indian.”

Boy scouts, girl scouts, day camps, school plays, mummers, tobacco shop Indian statues, etc. As Philip J. Deloria outlines in his book, Playing Indian, Americans have long been obsessed with appropriating and poorly imitating native dress, language, and customs for their own perceived benefits, from the Boston Tea Party to counterculture and the New Age movement.

Addressing the Power of Archives:

Though my search results may not have yielded what I wanted, they reveal something important, not just about American culture, but about archival collections themselves. Oftentimes, archival collections reflect what is perceived to be valuable by those who are in positions of power. At some point in time, someone decided that the traditions and rituals of the boy scouts was worthy of documenting, photographing, and saving. I am not contesting that this these photographs have historical significance and worth. What I am suggesting is that the histories and stories of American Indian communities, especially in urban areas, have traditionally not been viewed as significant or worthy of preservation. Because archives are often reflective of societal structures of power and authority, we must take note and proceed with caution.

For historians, this may mean treating “non-traditional” sources with the same amount of authenticity as traditional archival sources. For an archivist, this may mean investing in or attempting to acquire more diverse collections in the future. In order to participate in more robust conversations on history, we must first address the power of archives.

Featured Image: Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, February 2, 1960, Temple University Libraries Digital Collections.