Case Scenario:

A 50 year old male presents to physical therapy with a chief complaint of numbness and tingling as well as decreased sensation in his distal lower extremities, which he states has gradually gotten worse over the past 3 months. The patient has a 10 year history of Type II Diabetes, which he admits he does not manage well. When asked, the patient was unsure of his HbA(1c) and reports not measuring his glucose levels regularly or observing his feet for integumentary changes. After seeing his primary care practitioner last month, he was referred to an endocrinologist. The endocrinologist has recently prescribed him Lyrica for the nerve pain. The patient reports that the prescription makes drowsy and dizzy, and that “he’d really rather not take it”. The patient denies any acute trauma or injury, night pain, or changes in bowel or bladder. He is a construction worker in the local union and is on his feet for most of the work day. He states that the decreased sensation as well as the numbness and tingling in his toes is impacting his ability to perform at work, particularly climbing ladders at construction sites. He also says that he used to golf every other Saturday, but has not been able to because of the symptoms he is experiencing in his feet. His goal for physical therapy are to find the cause of his pain, and to be able return to golfing 2x/month, as well as safely climbing the ladder at work. After educating the patient on the importance of managing glucose levels through adhering to medications and through exercise and a healthy diet, the patient also made it a goal to exercise more, monitoring glucose levels after every meal, improve his diet, and monitor skin changes.

Outcomes:

HbA(1c)- 6.8%

NPRS: Average 5/10

PSFS: Golf- 3, Stand for >1 hour

Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale: 70%

Presentation:

Sitting posture examination appears within normal limits. When transferring from sit to stand, patient takes increase time to stand and weight bear through both lower extremities. Patient appears unsteady while standing and weight is transferred over right lower extremity. Lumbar active range of motion: within functional limits for flexion, extension, and right and left lateral flexion. Although, during these screens, patient was unsteady and had to use a “step-recovery” strategy to regain mild loses of balance. Lower quarter neuro examination consisting of dermatomes, myotomes, and deep tendon reflexes revealed decreased sensation along L5 and S1 (bilaterally), decreased deep tendon reflex (1+) left S2, and grossly normal myotomes. Slump test elicited no neural signs. When testing sensation using the Semmes-Weinstein Monofilaments, patient did not sense the 4.31 monofilament on the plantar surface of both lower extremities, which correlates to decreased protective sensation and diminished light touch. Supine examination revealed overall gross tightness in bilateral hamstrings, iliopsoas, and ITB. Central PAs over lumbar spine reproduced no pain or neural signs. Upon observation of plantar surface of feet, stage I ulceration was visible on both the heel and great toe of the left lower extremity.

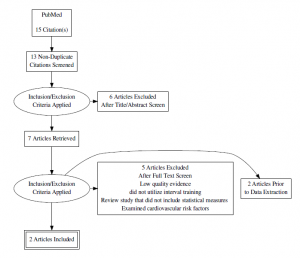

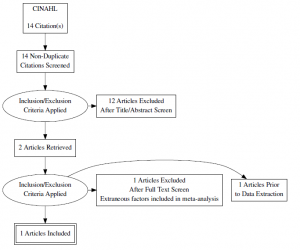

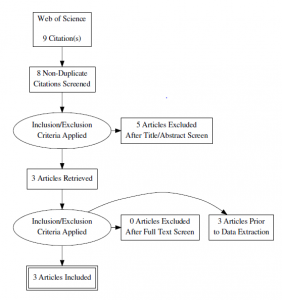

Search Strategy & Results

Inclusion Criteria, Article must include:

- Adults (>45 years old)

- Patients with Type II Diabetes

- Intervention includes interval training, OR aerobic AND resistance training, but not solely resistance training

- Utilizes HbA(1c) as a clinical marker/outcome measure

Exclusion Criteria, Article cannot include:

- Patients (<45 years old)

- Patients with Type I Diabetes

- Articles examining outcomes of resistance interval training

- Article did not use HbA(1c) as a clinical marker/outcome measure

Databases Searched:

- PubMed

- Search terms: “high intensity interval training” OR “aerobic interval training” AND “hemoglobin)” AND “diabetes”

- Madsen SM, Thorup AC, Overgaard K, Jeppesen PB. High intensity interval training improves glycaemic control and pancreatic beta cell function of type 2 diabetes patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133286 [doi]

- Mitranun W, Deerochanawong C, Tanaka H, Suksom D. Continuous vs interval training on glycemic control and macro- and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):e69-76. doi: 10.1111/sms.12112 [doi].

- Search terms: “high intensity interval training” OR “aerobic interval training” AND “hemoglobin)” AND “diabetes”

- CINAHL

- Search terms: “high intensity interval training” OR “aerobic interval training” AND “HbA(1c)” AND “diabetes”

- Terada T, Friesen A, Chahal BS, Bell GJ, McCargar LJ, Boule NG. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of high intensity interval training in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99(2):120-129. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.019 [doi].

- Search terms: “high intensity interval training” OR “aerobic interval training” AND “HbA(1c)” AND “diabetes”

- Web of Science

- Search terms: “type II diabetes” AND “aerobic interval training” OR “high intensity interval training” AND “HbA(1c)

- Alvarez C, Ramirez-Campillo R, Martinez-Salazar C, et al. Low-volume high-intensity interval training as a therapy for type 2 diabetes. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(9):723-729. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-104935 [doi].

- Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, et al. The effects of free-living interval-walking training on glycemic control, body composition, and physical fitness in type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):228-236. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0658 [doi].

- Balducci S, Zanuso S, Cardelli P, et al. Effect of high- versus low-intensity supervised aerobic and resistance training on modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes; the italian diabetes and exercise study (IDES). PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049297 [doi].

- Search terms: “type II diabetes” AND “aerobic interval training” OR “high intensity interval training” AND “HbA(1c)

Evidence Summary and Appraisal

| Author Date and Country | Patient Group | Outcomes |

Key Results |

Study Weaknesses |

| Mitranum, 2014, Thailand | 45 adults with T2DM | HbA1C%, BMI, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides

Health related physical fitness measures, vascular reactivity |

Both continued and interval exercise training groups showed decreases in fasting glucose concentration and improvements in lipid profiles. However, only the interval group had a statistically significant decrease in HbA1C levels when compared to the sedentary group.

Interval training may be a safe, efficient, and effective strategy for the secondary prevention of chronic cardiovascular complications of T2DM. |

Patients included in the study were of older age, sedentary, and on anti-hyperglycemic medications. Therefore, the results of the study may not be generalizable to the whole population of patients with T2DM.

Overall, the number of subjects in each intervention group may be considered small. |

| Terada, 2013, Alberta | 15 adults with T2DM | HbA1C%, BMI, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides

Subjective exercise experience scale, self-efficacy scales |

In both exercise intervention groups, fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, triglycerides, and body weight did not change from baseline to post intervention. There was no significant differences between interventions, which indicates the similar effectiveness of both types of interventions after accounting for baseline differences.

Both interventions are feasible and provide high satisfaction to participants in patients with well controlled T2DM. |

Findings need to be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and the presence of significant baseline differences in some characteristics despite random assignment.

The presence of a run-in phase required the attendance of 5/6 sessions to be eligible for the study and this could have resulted in a selection bias by favoring participants who were more likely to be compliant to the intervention. This selection of more compliant individuals strengthens internal validity but may weaken external validity.

There was relatively low HbA1C at baseline, as well as lack of statistical power to detect meaningful differences, which may be responsible for lack of change. |

| Karstoft, 2013, Denmark | 32 subject with T2DM | HbA1C%, BMI, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides

VO2max, blood pressure |

Walking exercise can be implemented as a free-living training method in T2DM. Interval walking training is superior to energy expenditure matched continuous walking training in regards to physical fitness body composition, and glycemic control.

BMI showed improvements in the IWT between pre- and post, as well as between CWT and CON groups. |

T2DM self-paced walking speed is low, and potentially too low to improve health-related outcomes.

There was large variability in the HBA1c changes in the IWT group. If a single subject with rapidly progressing, severe disease, who experienced serious deterioration in classic glycemic control variables after the training intervention was removed from statistical analysis, significant improvements in HbA1c were encountered in the IWT group. Additionally, a higher baseline HbA1C is associated with smaller training-induced reduction in HbA1C, which is evident that exercise responsiveness may be influenced by the underlying state of glycemic control. |

| Madsen, 2015, Denmark | 23 patients, 10 with T2DM and 13 matched healthy controls | HbA1C%, BMI, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides

Pancreatic beta-cell function, total fat, abdominal fat mass |

Among the T2D patients there was significant reductions of average fasting glucose concentration and HbA1C (clinically significant). In the control group, there was no significant change.

This study provides results that HIIT improves overall glycemic control and pancreatic beta-cell function in T2DM patients and HIIT is a health beneficial exercise strategy for these patient. Additionally, all subjects fulfilled the HIIT intervention, indicating that it could be integrated as a future exercise strategy in inactive T2DM patients. |

This study did not consider conducting the intervention with different duration of HIIT interventions.

More focus should also be addressed on more long-term HIIT intervention as well as individualized specific needs to address the intrasubject heterogeneity. |

| Balducci, 2012, Italy | 606 subjects randomized to a control group, low intensity group, or high intensity group. | HbA1C%, BMI, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides

Cardiovascular risk factors, physical fitness |

There was a reduction in primary endpoint HbA1C, and although slightly, was significantly higher in HI than LI subjects. When compared with the CON group changes over baseline in both the LI and HI subgroups were significantly more marked for HbA1C and BMI.

In low fitness individuals, such as sedentary subjects with T2DM, training at LI is just as effective as training at HI improving modifiable CVD risk factors and reducing CVD burden. Intensity is of less importance than volume and type of training when exercise is applied as a form of therapy. |

With a larger duration of the study, significant differences between the two subgroups would have emerged due to the progressively more pronounced difference in the duration of aerobic training and number of series of resistance training.

Only supervised exercise was performed at LI or HI, and working at HI in the absence of supervision is not recommended for safety reasons in individuals with T2DM. Due to the high volume of unsupervised physical activity achieved by both subgroups, only 1/3 of total PA was performed at different intensities. Differences in intensity in low-fitness individuals may not translate into absolute differences in aerobic and resistance workloads which are enough to produce a clinically significant difference in HbA1c. |

| Alvarez, 2016, Chile | Adult overweight or obese (BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2) with established diagnosis of T2DM for at least 12 months. | HbA1C%, BMI, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides

Blood pressure, changes in current medication |

There was significant interactions between inter- and intra-intervention in fasting glucose, HbA1C, BMI and triglycerides during 12 week follow-up.

The current low volume HIT program resulted in glycemic control improvements similar to those observes with a greater volume of exercise (>150min/week), and occurred even with a reduction in daily dosage of diabetes medications. Given that most T2DM patients are sedentary or insufficiently active, and lack of time is most frequently cited barrier to regular exercise participation, these findings are important implication for a public health perspective.

|

This particular study investigated only overweight or obese women with less than 5 years of diagnosis and no disease-related complications, which makes it hard to generalize to other populations.

There was only no control for dietary changes during the study and for physical activity during daily life after the intervention. |

| Author, Year | Country | CEBM Level of Evidence | PEDro Scale |

Study Design

|

| Trenda, 2013 | Alberta | Level 2 | 8/10 | Randomized control trial |

| Alvarez, 2016 | Chile | Level 2 | 7/10 | Randomized control trial |

| Mitranum, 2014 | Thailand | Level 2 | 7/10 | Randomized control trial |

| Karstoft, 2013 | Denmark | Level 2 | 6/10 | Randomized Control Trial |

| Balducci, 2012 | Italy | Level 2 | 5/10 | Randomized control trial |

| Madsen, 2015 | Denmark | Level 3 | 3/10 |

Non-randomized control trial/cross-sectional |

There is moderate-level evidence that suggests that high intensity interval training is an effective method for lowering the HbA1C levels in adults with Type 2 Diabetes. As the overall benefits of high intensity interval training are becoming more evident, it was prudent to justify its presence in the management of Type 2 Diabetes. However, it is difficult to draw a cohesive conclusion, as the studies examined utilize a variety of training protocols. Additionally, 4/6 studies compared high intensity training to continuous or low intensity, whereas 1 study compared high intensity to a non-exercise control group, and a final study compared the Type 2 Diabetes group to a healthy control group. This makes it challenging to draw a consistent parallel between the current published literature and the stance practitioners should take when prescribing exercise for patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Although many of the studies presented statistically significant results in favor of high intensity interval training, only one study was able to produce clinically significant results when comparing high intensity interval training to continuous training. In patients with already well-managed Type 2 Diabetes, training at either high or low intensities did not seem to make an effect on HbA1C values. The American College of Sports Medicine along with the American Diabetes Association recommend >150 minutes of low-moderate exercise per week for the management of Type 2 Diabetes. HIIT provides these patients the same benefits, but the training protocols require less time and allow for periodic rest breaks. Overall, it is conclusive that both high intensity interval training and low intensity interval training can be utilized in

the management of Type 2 Diabetes. But, what sets high intensity interval training apart from other intervention is that it is more efficient, cost effective, and less time consuming, making it more favorable and potentially leading to higher adherence rates. There a variety of different forms of HIIT, which makes it utility in practice extremely practical and can be utilized in all physical therapy settings, and when prescribed from a health care practitioner, specifically a physical therapist, it can be safely performed in the home as a part of a home exercise program.

Application of Evidence

Sample Protocol:

| VARIABLE | WEEKS 0-4 (3x/week) | WEEKS 5-9

(3x/week) |

WEEKS 10-13

(3x/week) |

WEEKS 14-16

(3x/week) |

| Exercise Intensity (% Age heart rate reserve) | 90-100 | 90-100 | 90-100 | 90-100 |

| Exercise Duration (s) | 30-34 | 38-44 | 46-50 | 52-58 |

| Number of exercise bouts | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Recovery Intensity (% Age predicted heart rate reserve) | <70% | <70% | <70% | <70% |

| Recovery Duration (s) | 120 | 108 | 100 | 96 |

| Number of recovery bouts | 9 | 11 | 13 | 15 |

| Total Time Commitment/day | 22-22.5 min | 26.1-27.1 min | 30.9-31.7 min | 36.1-37.5 min |

High intensity interval training can be easily implemented into practice across all physical therapy settings. There is a large number of forms of high intensity training that can be utilized in practice. Depending on the technology available, 70-90% VO2max, 70-90% max HR, or Borg Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale can be used to ensure the patient is exerting themselves at the appropriate intensity. One of the protocols used in the reported studies can be used or modified to best suit the patient.

Depending on their preferred method of exercise, interventions can be tailored to best suit the desires/preferences of the patient. As presented in the literature, training programs can implement any form of exercise, from walking, cycling, and jogging. Other forms could include circuit training, such as plyometrics, or skipping rope. The main goal of treatment although, is to reach a particular pre-determined intensity, whether determined through heart rate, VO2 max, or RPE.

Based on our patient’s presentation, he will benefit from comprehensive and progressive balance training. Exercises can be taught to the patient in the clinic, but then can be completed at home a part of a home exercise program. Due to the flexibility of the training programs and its feasibility to be completed outside of the clinic, the patient should only have to be seen at the time of training progressions, in the absence of adverse events.

References

1. Alvarez C, Ramirez-Campillo R, Martinez-Salazar C, et al. Low-volume high-intensity interval training as a therapy for type 2 diabetes. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(9):723-729. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-104935 [doi].

2. Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, et al. The effects of free-living interval-walking training on glycemic control, body composition, and physical fitness in type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):228-236. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0658 [doi].

3. Madsen SM, Thorup AC, Overgaard K, Jeppesen PB. High intensity interval training improves glycaemic control and pancreatic beta cell function of type 2 diabetes patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133286 [doi].

4. Mitranun W, Deerochanawong C, Tanaka H, Suksom D. Continuous vs interval training on glycemic control and macro- and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):e69-76. doi: 10.1111/sms.12112 [doi].

5. Terada T, Friesen A, Chahal BS, Bell GJ, McCargar LJ, Boule NG. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of high intensity interval training in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99(2):120-129. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.019 [doi].

6. Balducci S, Zanuso S, Cardelli P, et al. Effect of high- versus low-intensity supervised aerobic and resistance training on modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes; the italian diabetes and exercise study (IDES). PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049297 [doi].