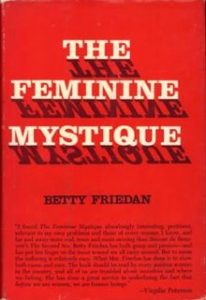

In, “Rethinking Betty Friedan and the Feminine Mystique: Labor Union Radicalism and Feminism in Cold War America”, Daniel Horowitz looks at how Betty Friedan’s portrayal of herself as someone who was trapped by the feminine mystique was part of a reinvention that she constructed and promoted as part of her book The Feminine Mystique (1963). In reality, this portrait hid her active participation in union activity in the 1940s and early 1950s; thus whilst Friedan gave the impression of herself in the late 1940s as a woman who embraced domesticity, motherhood, and housework, and only became interested in feminism when she discovered what she called “The Problem That Has No Name,” conversely the written record of Friedan’s life presents a different story.

At college, Horowitz argues that Friedan first developed as a radical, becoming editor-in-chief of the campus newspaper in 1941, a paper which supported American workers and their labor unions in their struggles to organize and improve their conditions. Following college with a career as a labour journalist, Friedan was exposed to a variety of issues, such as sexual discrimination, which subsequently shaped her emergence as a feminist. As a labor journalist she supported working-class women, even African Americans, and whilst we can’t assume that these issues which she wrote about were necessarily most important to Friedan, it is nevertheless a good indicator or suggestion as to what she generally believed in. Furthermore, when she then moved onto free-lance writing, her articles contradicted her claim that she had contributed to what she later attacked in The Feminine Mystique.

At college, Horowitz argues that Friedan first developed as a radical, becoming editor-in-chief of the campus newspaper in 1941, a paper which supported American workers and their labor unions in their struggles to organize and improve their conditions. Following college with a career as a labour journalist, Friedan was exposed to a variety of issues, such as sexual discrimination, which subsequently shaped her emergence as a feminist. As a labor journalist she supported working-class women, even African Americans, and whilst we can’t assume that these issues which she wrote about were necessarily most important to Friedan, it is nevertheless a good indicator or suggestion as to what she generally believed in. Furthermore, when she then moved onto free-lance writing, her articles contradicted her claim that she had contributed to what she later attacked in The Feminine Mystique.

Compared to her more radical ideas and activities in the years before she wrote The Feminine Mystique, it is therefore surprising that she would later come to exclude more radical agendas from entering the women’s movement. Horowitz briefly illuminates this idea, stating that “Friedan’s experiences in the 1940s and early 1950s help explain but do not excuse her attack in 1973 on “disrupters of the women’s movement”” [1] The tensions which Horowitz describes is the conflict between straight feminists such as Friedan and the “man-hating” lesbians, who Friedan believed would hinder their cause. It is well recorded that Friedan severed ties with known lesbians and even spoke out about them in the New York Times, however her homophobia culminated when Friedan referred to the lesbian contingent as a “lavender menace” during a 1969 NOW meeting.

As someone who has an interest in gay and lesbian histories, the image of Friedan as a woman who rejected or excluded minorities is the one I have come into most contact with, hence my surprise at this article, which suggests that Friedan, and by extension liberal feminism, actually had quite radical origins. I am therefore questioning what other historical figures do we think of in a way which hides the true realities of their story. I don’t doubt that there are probably tons, a fact which is equally fascinating as it is frustrating.

[1] Daniel Horowitz. “Rethinking Betty Friedan and the Feminine Mystique: Labor Union Radicalism and Feminism in Cold War America.” American Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 1, 1996. pp. 1-42. P.27