“In Our Jeans” (2024) by Emily Farrell

15 x 20, machine-stitched, painted, and drawn on recycled denim and fabric

“No current day adult will be alive in the year in which African Americans as a group will have been free for as long as they had been enslaved. That will not come until the year 2111.”

— Isabel Wilkerson

SUMMARY

The physical fiber art piece “In Our Jeans” was created to highlight one product of the caste system: denim. Both cotton and indigo, key materials in denim fabric, were popular crops during the time of slavery. Cotton cloth was also what enslaved people wore while working because it was the only kind of fabric that could withstand the brutality of the labor they were subjected to (Coard, 2022). How often do we consider the history of denim when we throw on a pair of jeans? In my reading of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, I learned that caste is pervasive. Its presence at the foundation of our country has allowed it to fester in every fiber of modern society today, whether we realize it or not, and we must acknowledge and disrupt its presence to build a better, freer, and more radically empathetic, equitable society.

Symbolism

American flag (background)

The background of the piece is a vertical American flag, and it was constructed using light, dark, and medium washes of denim. I chose to recreate the flag because of how iconic its symbolism is. Often, the flag is hung as an indication of American pride. I incorporated it here to challenge that notion of pride and confront it with a history, that of slavery and caste, that we should take no pride in.

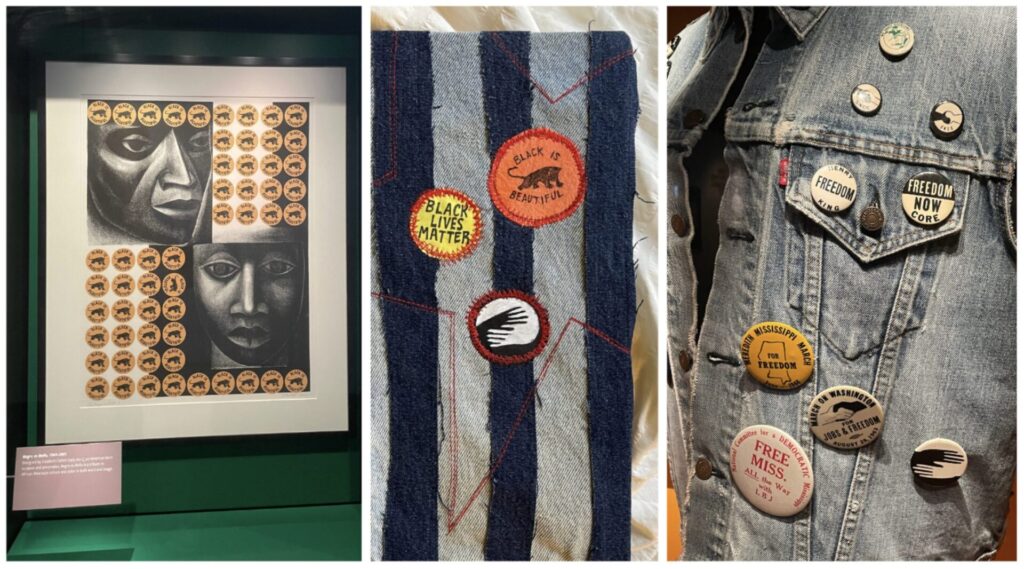

Protest pins (top right corner)

While the piece’s main theme is to illuminate the history of denim, I also wanted to include symbols that speak to the importance of disruption. The pins I pulled inspiration from were found on artifacts and artistic imagery in the National Museum of African American History and Culture and online. Created with recycled fabric, paint, and pens, the pins include combined imagery and words from the Black Panther Movement, SNCC, and the Black Lives Matter movement. I felt it was essential to include a pin from the Black Lives Matter movement since it demonstrates that the fight for racial justice and equity is ongoing.

Red star (top right corner)

The machine-stitched red star was placed to frame the protest pins and disrupt the pattern of the American flag. The contrasting color of red also frames each of the three protest pins.

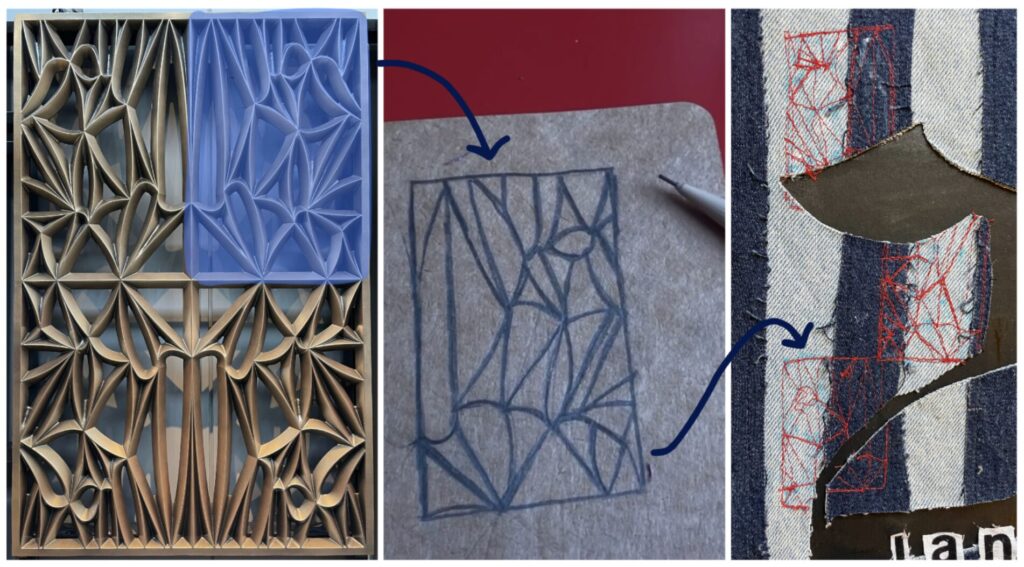

Red stitching (bottom left corner)

In the same red thread, three panels of stitching replicate a piece of the motif used in the NMAAHC’s metal exterior, which was inspired by the ironwork of enslaved African Americans (The Building, 2023).

“2111” cutout (bottom third)

In Caste, I learned that 2111 is the year in which African Americans, as a people group, will have been free for as long as they were enslaved in the United States (Wilkerson, 2020, p. 47-48). This number emphasizes that, even by the metric of time, we still have so far to go. If presented in a gallery space, the quote from Caste that explains this year’s significance would be included next to the art piece. Instead of adding more denim to the work, I chose to cut into the fabric of the flag to symbolize the way that slavery preceded the founding of America and the way it has been covered up or glossed over.

“land of the free” letters (bottom edge)

The “land of the free” letters are meant to be seen in direct conjunction with 2111. It’s a phrase many Americans recognize and comprehend, but as we discussed in class, only a select group has believed and experienced it since the founding of America. It was included in similar irony as the flag itself.

Unfinished edges (throughout)

One thing I like about fiber arts is that it wears away with time. For a piece like this, I find that to be not just a unique feature but an important part of the broader discussion of caste. A famous analogy Wilkerson included in Caste is that America is like an old house. Ignoring the problems at its foundation won’t make the problems disappear, it will continue to fall apart. The unfinished edges of this piece will also continue to fray and unravel over time.

DIRECT INSPIRATION

Click the Image Below to Watch a Video of My Process

In addition to Wilkerson’s Caste, my inspiration for “In Our Jeans” came from visits to the National Museum of African American History, the National Museum of African Art, and the National Museum of the American Indian. In the video above and the photos below, I’ve documented the visual inspiration I pulled together to fuel this piece and its imagery.

LEFT: “Negro es Bello II” (1969, printed in 2001) by Elizabeth Catlett. Ink on rag paper. On display at NMAAHC. MIDDLE: Protest pins on “In Our Jeans.” RIGHT: “Commemorative denim vest with buttons assembled by Joan Trumpauer Mulholland” (1960s, assembled 1980s). Denim and metal. On display at NMAAHC.

LEFT: Iron motif used along the outside of the NMAAHC, created by the architectural team of Freelon, Bond, David Adjaye, and Hal Davis in 2009. MIDDLE: My sketch of the top panel. RIGHT: Motif sewn into fabric with red thread, intersected by the “2” cutout.

LEFT: American flag in “In Our Jeans.” RIGHT: “Nations: A Mourning Tribute” (2001) by Jenny Ann Taylor (Chapoose), Uintah Ute. Loom beadwork, sewn. On display in the National Museum of the American Indian.

LEFT: “An Offering” (2017) by Stephen Towns. Mixed media. Three of the seven panels that were on display at NMAAHC. RIGHT: “It Is Only When You Lose Your Mother That She Becomes Myth” (2020) by Ayana V. Jackson. Mixed media. On display in the National Museum of African Art.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

— Ida B. Wells

PERSONAL REFLECTION

While reading Caste, I remembered a video I watched a few months back about Tremaine Emory’s brand Denim Tears (McLean, 2020). Emory is known for printing wreaths of cotton on denim, reclaiming the fabric while simultaneously reminding the world of its history. When I first watched that video, I was surprised I had never considered jeans to be connected to slavery. Reading Caste taught me that there are connections everywhere and nothing is free from the impact of caste. Those ideas were further emphasized in our class sessions and museum visits during the Rocking the World course. Each of these components influenced me to use denim to “turn the light of truth” on what I’d learned, creating a piece about the fabric, its history, and disrupting caste in America.

It took me a while to decide how I wanted to visually represent what I had learned. I had initially thought I would include some kind of portraiture throughout the piece, but I was hesitant to tie all of the meaning to a particular face or figurehead. Caste is a plural issue we all have to reckon with, and I think the American flag does a better job of communicating that collective responsibility. Physically creating the piece took me upwards of 10 hours, and I found myself reflecting on the effort of sewing, art, and craft throughout the process. This led me to think further about the transnational caste system that is created by the common practice of outsourcing. Working on the piece allowed me to develop a greater appreciation for the work that goes into making fabric and creating the things I wear and enjoy.

STEPS OF ACTION

- Consider Caste: Caste is present all around us, and once you know to look for it, you won’t be able to stop seeing it. Clothing is just one place to start considering caste. Next time you try on a pair of jeans, consider the history that they have.

- Consume with a Conscience: It’s no secret that patterns of mass consumption have harmed people across the world, our climate, and our psyche.

- Disconnect and De-Influence Yourself: It’s easy to get caught up in what we think we need when we are surrounded by advertisements outside, on TV, and online. Taking a step back can help curb impulse buys and discontentment.

- Shop Black-Owned Brands: If you’re spending money, consider spending it with a Black-owned brand. Shop locally when you can. Here are some Black-owned clothing brands, boutiques, and secondhand shops that are local to Philly:

- Engage with Supplemental Educational Resources: There are many resources available to take this study deeper. In reflecting on denim today, the fast fashion industry must be mentioned. Nearly all clothing today is produced outside of the U.S., and growing fast fashion brands are pressuring for cheaper production, cutting workplace safety, wages, and environmental regulations to turn a profit. Here are resources to explore this topic:

- The True Cost — This documentary exposes the damages we are often quick to ignore when shopping from fast fashion brands.

- Made in Bangladesh — Following the journey of one Bangladeshi woman, this documentary takes a close and personal look at outsourced clothing production.

- Shein Is the World’s Most Popular Fashion Brand—at a Huge Cost to Us All — This is one of many articles about the sustainability of Shein, a fast fashion retailer with unimaginably low prices.

- Good on You — Not sure how to find a “good” clothing brand? This ever-growing directory was created as an all-in-one spot to read factual information on the sustainability and social impact of most major brands.

Additional References

Coard, M. (2022, March 1). Enslaved blacks invented Blue Jeans. The Philadelphia Tribune. https://www.phillytrib.com/commentary/michaelcoard/enslaved-blacks-invented-blue-jeans/article_57de5262-5b78-534d-a133-bfc406f87a78.html

McLean, C. (2020, January 24). Tremaine Emory on How Slavery Inspired His New Denim Tears Collection. The Face. https://theface.com/style/denim-tears-tremaine-emory-levis-no-vacancy-inn-acyde-fashion

The Building. National Museum of African American History and Culture. (2023, November 22). https://nmaahc.si.edu/about/building Wilkerson, I. (2023). Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. Random House.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.