United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Introduction

Hi, my name is Maria Utz and I am a senior journalism and political science double major at Temple University. I took the “Rocking the World” course to complete my minor in communication and activism. I chose these disciplines because I’ve always believed that the way information is communicated to the public is incredibly important and can either spark or hinder social change. As a journalism major during both the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 election, I’ve seen the effects of misinformation and disinformation running rampant in this country. Whether it be vaccine misinformation or election denial, how do you rationalize with someone who has a completely different set of “facts” and reality than you do? How can we eliminate this problem? This has been on my mind for the entirety of my undergraduate career.

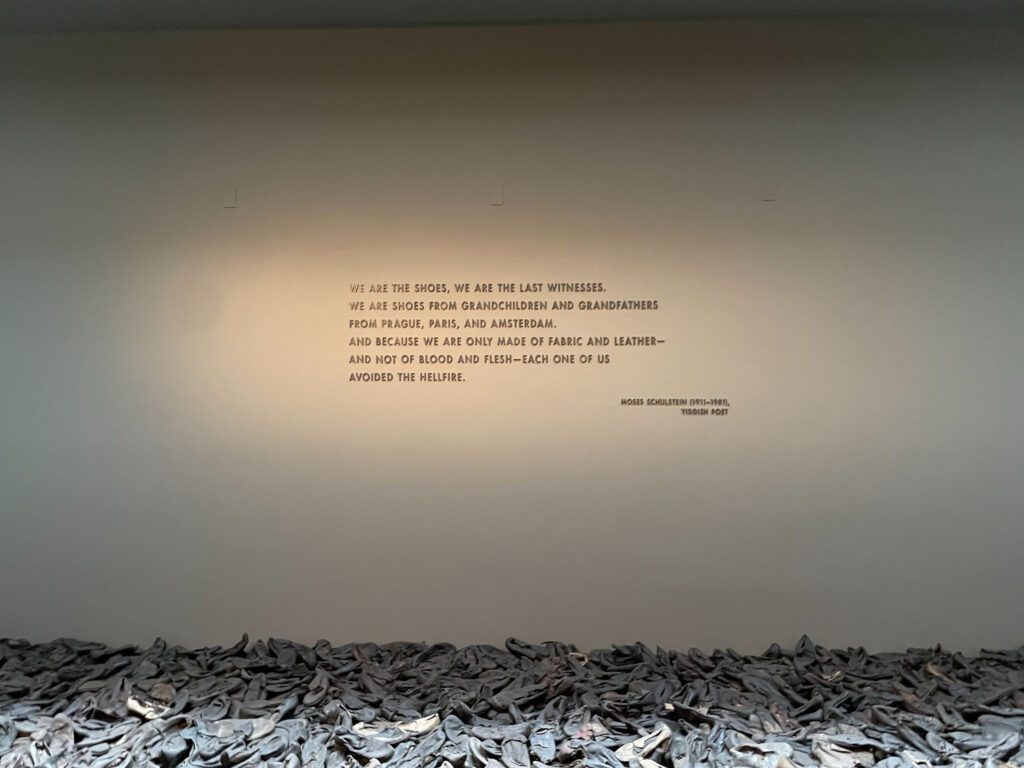

During our trip to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., I was particularly impacted by the physical evidence that was left behind. For example, this pile of Holocaust victims’ shoes put a pit in my stomach.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

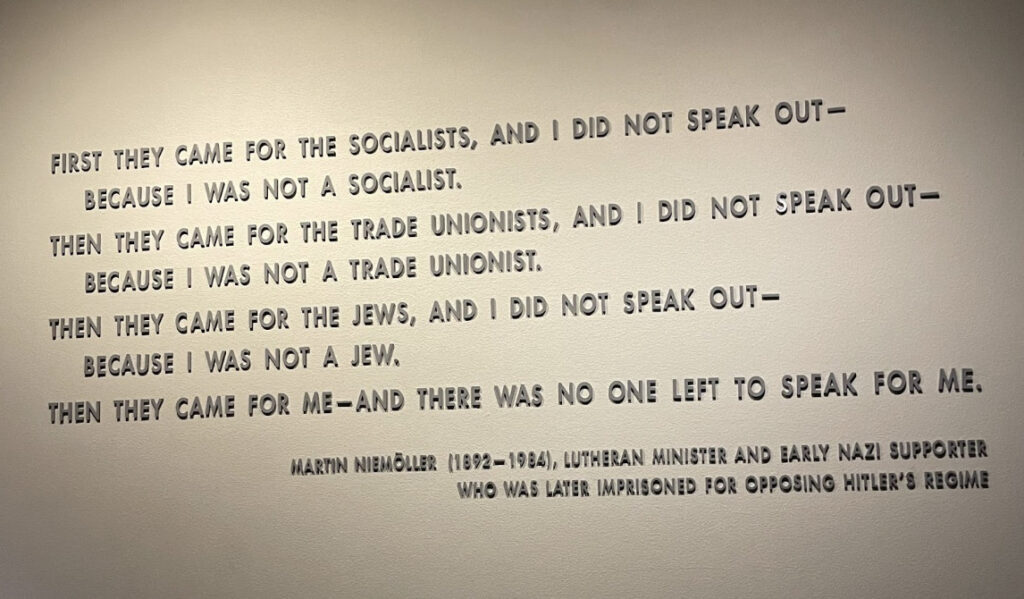

Immediately, I thought about the existence of Holocaust deniers. A survey of 11,000 millennial and Gen-Z Americans by the Conference on Material Claims Against Germany found that only 90% of respondents were sure that the Holocaust had really happened (Ramgopal 2020). When I saw the piles of shoes and watched videos of firsthand accounts from survivors, all I could think was, “how could anyone think this wasn’t real?” I was seeing all of the evidence right in front of me.

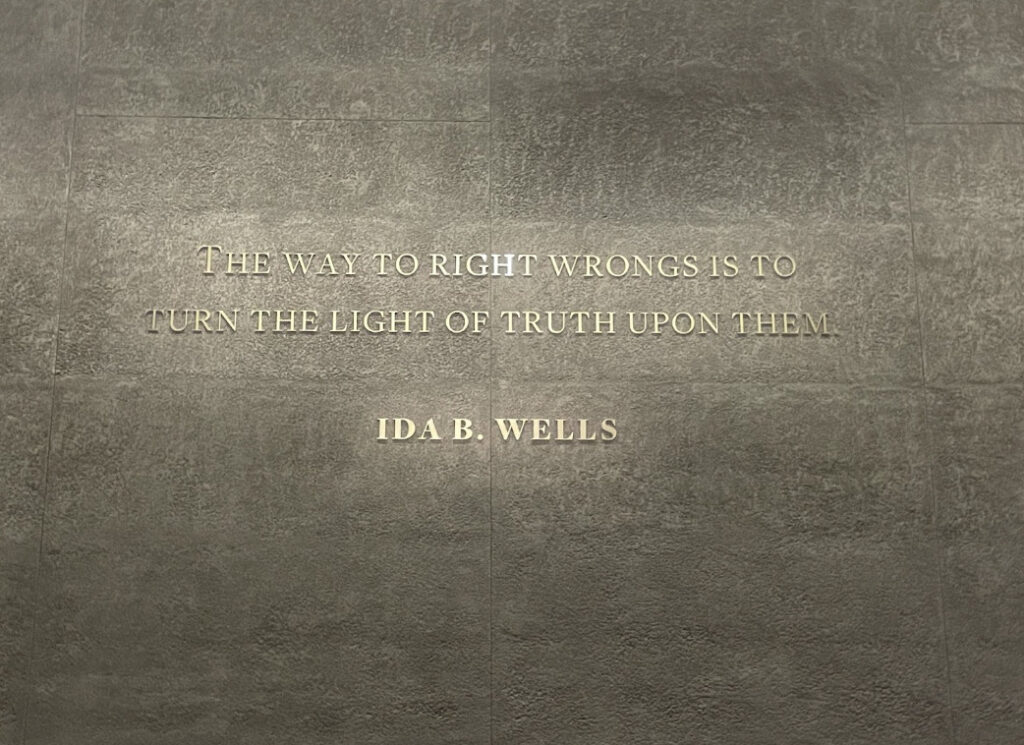

As we learned in the course, one of the ways to disrupt stereotypes and oppressive systems is to educate people about them. For this reason, I am focusing my project on education, not just on the Holocaust, but on information and media literacy. It’s imperative for students to learn from an early age how to distinguish between truth and fabrication so that later on in life they can acknowledge the existence of oppressive systems and begin to combat them. If people don’t believe the Holocaust really happened, we are in a poorer position to recognize and prevent the next genocide before it happens. Likewise, if people don’t believe that systemic racism persists in America, we can’t deconstruct it. I found this Ida B. Wells quote on the wall at the Museum of African American History and Culture particularly poignant:

National Museum of African American History and Culture

So how do we prepare young learners to recognize the truth? Here are some strategies I found in my research.

On an Individual Level: Start Young

Media literacy doesn’t have to start in the classroom, it can start with parents or guardians at home. Research from UT Austin found that children begin to understand the difference between fantasy and reality around the age of 4 (Leahy 2006). While it’s unlikely that parents will succeed in teaching their preschool aged children about “fake news,” parents can use their children’s favorite movies and TV shows to help children engage with the media they’re consuming more critically from a young age. For example, Common Sense media, a nonprofit organization that provides resources to parents raising children in the digital age, provides parents tips on introducing media literacy to their preschoolers.

According to Common Sense, it’s imperative that children are told that the media they’re consuming, whether it be TV shows, advertisements or computer games is information that was created with a specific intent. Without any intervention from adults, children typically don’t recognize commercials as anything other than entertainment (or maybe even reality) until the age of 7 (Common Sense Media 2020). Common Sense suggests, “Point out when favorite characters are used to sell products, and ask kids if they’re more likely to want something if, say, SpongeBob is on the packaging” (Common Sense 2020).

Common Sense also suggests using young children’s favorite TV shows and movies to get them more actively engaging with what they’re watching. Parents can make connections between TV characters’ actions and real world consequences. For example, parents can make comments like, “Spongebob is a good friend to Patrick” to point out positive behavior to their children or create an example out of negative behavior, like “Mr. Krabs is greedy.”

While these tactics are far simpler than identifying false information about a state-sposored genocide, it equips children early on to engage critically with media in an easy, digestible and fun way.

In Classrooms: Teach “Lateral Reading”

For children that are beginning to pursue research projects, even elementary ones like a brief report on a historical figure or their favorite animal, they can be taught to practice “lateral reading,” a concept originating from the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG). Many of us are familiar with “vertical reading,” even if we don’t know it by name. “Vertical reading” is how we might consume a book, just reading down the page and taking the information at face value. However, “vertical reading” doesn’t work in the digital age. When we go on a website and read down the page without consulting any other sources, we only see exactly what the site’s creator wants us to see. That makes us more likely to take a website with a professional looking logo and pretty layout as legitimate, even if the content on the website is false (CrashCourse 2019).

“Lateral reading,” on the other hand, is the process of opening a second, or even third or fourth tab in your web browser to do additional research on your original source (SHEG 2022). For example, if a student were to research the Holocaust and use the site for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, they could open additional tabs and verify from a variety of other sources that the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is a trustworthy source to learn about the Holocaust. In the other tabs, students might learn how history scholars perceive the museum, how Holocaust survivors perceive the museum, and information like who is in charge of the museum and how it is funded.

Lateral reading is a particularly important skill to help students understand more complex issues. For example, while the vast majority of people do believe the Holocaust took place, there are (alarmingly) common misconceptions about whose fault the Holocaust was, and just how severe it was. The study I previously cited from the Conference on Material Claims Against Germany found that 11% of respondents thought that Jews caused the Holocaust, and some young adults were unaware of the amount of people killed, thinking it was closer to 2 million (Ramgopal 2020). For students to understand any social issue, lateral reading can be an extremely valuable skill to help students evaluate their sources and correct misconceptions about historical events. This video by John Green for CrashCourse explains this skill very well and may be helpful for teachers to use in classrooms.

A Broader Change: Utilizing Libraries and Librarians

As an elementary schooler, I attended a “library” class once a week. In the younger grades, this typically involved the librarian reading us a story and allowing us to pick out our own books afterwards. By fourth and fifth grade, we were learning about how to utilize informational books like the encyclopedia, almanac and atlas. From speaking to my peers, I’ve learned that a lot of schools don’t send their elementary schoolers to a library class. As the internet and social media have grown since my elementary school days, I think librarians could be of particular value in teaching students about information and media literacy in the digital age.

The American Library Association agrees. The American Library Association published an article in which the authors suggest, “librarians can play the role of information educator, not just providing access to information but helping to empower users by teaching them to understand which information to trust” (Spratt and Agosto 2017). In terms of Holocaust education, librarians can teach children to differentiate between a primary source, like the Diary of Anne Frank and newspapers from WWII, from less reliable sources like online discourse.

Librarians also have the skillset to teach young adults how to create a healthy “news diet,” in which they consume information from a variety of news outlets to get the full picture of current events, as told from all perspectives (Spratt and Agosto 2017). After all, journalists are human beings, and although they try to remain impartial, choosing what to include in a story, or what is even deemed as “newsworthy” has social repercussions. Consuming news from a variety of sources ensures that students are reading stories from several different journalists, each of whom has their own unique set of lived experiences they bring to the table when reporting. Repositioning librarians as “information educators” and requiring library classes in schools to promote news, information and media literacy would be a greater societal change that could equip young people with the skills they need to distinguish fact from fabrication.

Conclusion

No one can rock the world without knowing the realities of our world. With an abundance of information sources online, it can be difficult to know which information sources to trust. My experience at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the existence of Holocaust deniers inspired me to think about how we can make sure young people are learning how to access accurate information, and how to know when online information is untrustworthy. Information literacy can empower students to learn accurate information about humanity’s mistakes of the past, like the Holocaust, and also how systems of oppression persist in the present day to uphold a caste system based on race. As Isabelle Wilkerson wrote in her book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, “You cannot solve something that you do not admit exists,” (Wilkerson 2020, 385) and knowing where to find accurate information is the first step in this admission.

Sources

Common Sense Media. (2020). How can I use TV and movies to Teach My Kids Media Literacy? Common Sense Media. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/articles/how-can-i-use-tv-and-movies-to-teach-my-kids-media-literacy

CrashCourse. (2019). Check Yourself with Lateral Reading: Crash Course Navigating Digital Information #3. YouTube. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GoQG6Tin-1E&t=9s.

Leahy, C. (2006, November 27). Young children learn to distinguish between fact and fiction, research at University of Texas at Austin finds. UT News. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://news.utexas.edu/2006/11/27/young-children-learn-to-distinguish-between-fact-and-fiction-research-at-university-of-texas-at-austin-finds/#:~:text=Children%20are%20able%20to%20distinguish,University%20of%20Texas%20at%20Austin.

Ramgopal, K. (2020). Survey finds ‘shocking’ lack of Holocaust knowledge among millennials and Gen Z. NBC News. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/survey-finds-shocking-lack-holocaust-knowledge-among-millennials-gen-z-n1240031.

Spratt, H. E., & Agosto, D. E. (2017, Summer). Fighting fake news: because we all deserve the truth: programming ideas for teaching teens media literacy. Young Adult Library Services, 15(4), 17+. https://link-gale-com.libproxy.temple.edu/apps/doc/A498995707/AONE?u=temple_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=a93e334f

Stanford History Education Group. (n.d.). Intro to lateral reading. Civic Online Reasoning. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://cor.stanford.edu/curriculum/lessons/intro-to-lateral-reading?cuid=teaching-lateral-reading

Wilkerson, I. (2020). Caste: The origins of our discontents. Thorndike Press Large Print.