INFORMAL EDUCATION

In high school and throughout my time studying to achieve a University education, I worked at hardware stores. These experiences required me to become familiar with materials of various trades, operate machinery, and interact with the general public. These experiences still prove useful when directing the design and construction of Philadelphia Flower Show exhibits, or other design or design-build projects.

Home Depot

Plumbing Sales

Omaha, Nebraska, September 2001 – November 2001

Home Depot

Outside Garden, Lumber, Building Materials

Columbus, Georgia, February 2000 – August 2001

Home Quarters Warehouse

Plumbing and Electrical Sales

Columbus, Georgia, November 1997 – December 1999

Payless Cashways Building Materials and Lumberyard

Department Sales Manager; Hardware, Tools, Seasonal

Also became familiar with Paint, Plumbing, Electrical Departments

Bellevue, Nebraska, April 1994 – October 1997

ACQUIRED SKILLS: Re-key & master key locks; mix paint and stain; cut blinds, shades, chain, lumber, pipe, and wire; operate forklifts, order pickers, reach trucks, and skidsteers

FORMAL EDUCATION

2001 Master of Landscape Architecture, Cum Laude , Auburn University; College of Architecture, Design, and Construction; School of Architecture; Auburn, Alabama

1999 Bachelor of Science in Environmental Design, Cum Laude, Auburn University; College of Architecture, Design, and Construction; School of Architecture; Auburn, Alabama

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MASTER’S THESIS

My thesis is best stated in three parts: we as humans understand nature through language and architecture. Landscape is the sum of language, architecture, and nature. Our identities, both shared and individual, are created in the relationships of each of these – language, architecture, and nature.

I did not use typical landscape architectural methods to argue this. I did not find a site, nor was I given one. I did not define a program. Yes, there was design, but there were no plans, sections, elevations, and perspectives. Instead, I wrote a book.

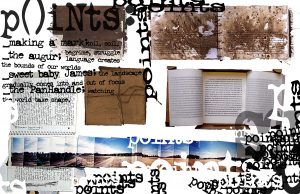

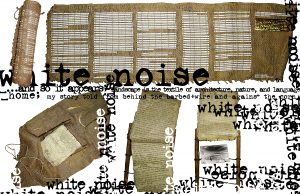

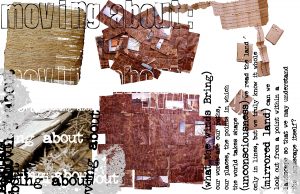

Night Clouds is composed of four sections each addressing a different aspect of the thesis. “Points” begins the book with four chapters discussing the significance of places as points in the landscape – how they are acknowledged, comprehended, and mapped both on the earth and in our minds. “White Noise,” the second section, focuses on the background or the context of the places in which we live. “Moving About” details the contributions paths and movement have in defining points within the contextual landscape. “Lingering,” the last section, is an attempt at understanding the emotions that are created by staying in a place, by living, by dwelling.

When originally presented in a traditional book format, Night Clouds lost something. Many of the study models, drawings, and day maps (constructions of discarded and found materials while on site) that informed the writings lacked character and texture when photographed or scanned. The connection between the underlying ideas of the text and the studio work was severed. To join them, to make the text, the ideas within, and the studio work whole, I followed the suggestion of a professor and assembled an artist’s book.

Mud, copper, paper, wood, wax, wire, barbed wire, burlap, twine, cement board, and a cigarette all assembled, arranged, ordered and bound in some way was the result. Each of the thirteen chapters had its own idea dictating the construction of the chapter.

“Making a Mark,” tells the story of Josie and Will Hendershot, emigrants, homesteaders, traveling across the unsettled prairie of Nebraska. The marks they make upon settling – the sod home, the chimney, and later the windmill – are the architectural points around which their notion of the landscape becomes comprehensible. Their story is one of hardship and toil. It is this last word “toil” that I used to inform the chapter’s construction. Toil, as defined by Webster’s Dictionary, means to struggle, begrime, but also, to soil. Josie and Will’s story begins in a covered wagon as they are traveling across the prairie. They are hungry, thirsty, and loved ones have died along the way. When they decide to settle and build, life is hard; their struggle, their toil is hard. The amount of mud on the page communicates this. For the reader of the chapter the text is difficult to read, but as Josie and Will’s life gets easier, as they make shelter, find food, water, and establish themselves in the landscape, the struggle decreases and so, too, does the mud on the pages of the chapter.

“Sweet Baby James,” is the story of James Graham, a Virginian who caught ‘Alabama Fever’ with his wife and traveled to Alabama in search of a new life. Instead of a vast, open, limitless plain, James and his family carve into the confined woods of Alabama and clear ground for food and shelter. He ventures outward finding a clearing, a rock outcrop, and other landmarks, man-made and natural, which he and his family name. Eventually, gradually, the landscape becomes clearer, more easily understood, more focused. With this in mind the text has been manipulated to blur in and out of focus from page to page. Just as the landscape is capable of being illegible, unintelligible, so, too are the text and the chapter. The motion within which this is done is also addressed. Rather than turning the pages from right to left, they turn both right to left and left to right mimicking the motion of the hands when wading through brush, murky water, or when clearing ground.

“The Panhandle” was the result of a design experiment. An open, grassy field off campus ground intrigued me. I grabbed a notebook, a camera, packed a lunch, skipped studio, and spent the day sitting in the field trying to figure out why I was drawn to it. The revelation came sometime after lunch, after tiring of sitting and listening, watching and wondering why. I got up walked around and began to notice small landmarks – an anthill, a forgotten metal lawn chair, a soaked low spot. The field I once thought empty and featureless was anything but. I mapped my findings, putting them down on paper and in my mind. “The Panhandle” was an expedition, a simple exploration of unknown earth – a documentary of land that acquired space, dimension, and importance.

These are but three descriptions of how the idea of each chapter in Night Clouds was shown in a form other than words. There are more: printed text cut into strips and woven into burlap mimics the weave of language into or onto the earth. Lines of another story are revealed one by one, piece by piece just as landscapes are revealed while moving across them. This paring down of the work, this critical editing was necessary for creating the artist’s book, but it also allowed me to understand in the simplest, most basic terms possible how people experience landscapes.