Beyond the Notes presents

Beyond the Notes:

He’s Got the Whole World: A Celebration of Black Voices

Wednesday, April 9th, 2025, 12:00 PM

Charles Library Event Space

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged.

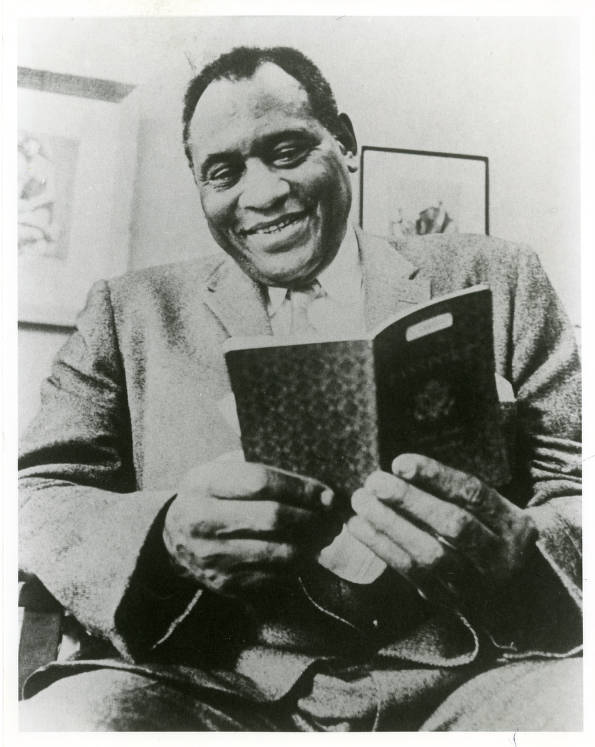

This month, Beyond the Notes will feature Boyer graduate Shawn Anderson as he presents a program of timeless songs by trailblazing Black composers whose groundbreaking contributions to classical music often go uncelebrated, featuring Boyer students and friends. Figures like William Grant Still (1895–1978), Harrison Leslie Adams (1932–2024), Robert Owens (1925–2017), Harry T. Burleigh (1866–1949), Moses Hogan (1957–2003), and Edward Boatner (1898–1981) made a lasting impact on the musical landscape, and in honor of this concert, we’ll be examining the life of another trailblazing figure, Paul Robeson (1898–1976). He was a man of rare breadth—an extraordinary athlete, a powerful actor and singer, and a fierce advocate for justice and equality. His life, lived across the first three-quarters of the 20th century, defied easy categorization and challenged a nation to reckon with its conscience. From college football fields to global concert halls, from Broadway stages to political blacklists, Robeson’s journey is both inspiring and sobering—a story of immense talent and unwavering principle. Alongside Robeson’s story, we’ll be featuring images of the Blockson Collection’s Paul Robeson digitized collection.

From Athlete to Scholar: Robeson at Rutgers

Born in 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, Paul Robeson was the youngest of five children. His father, a formerly enslaved man turned Presbyterian minister, and his mother, a teacher, instilled in him the importance of education, discipline, and integrity. These values would form the bedrock of Robeson’s life.

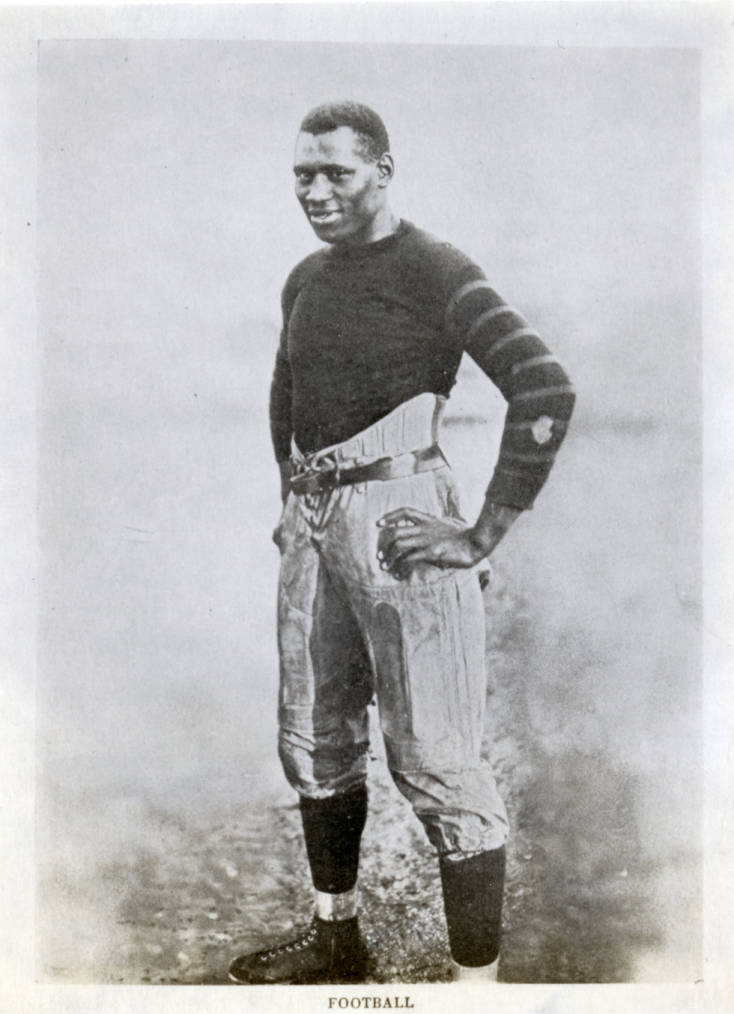

Robeson’s academic and athletic gifts became evident early on. In 1915, he earned a scholarship to Rutgers College (now Rutgers University), becoming only the third African American student to attend the institution at the time.1 There, he was a standout in every sense. On the football field, Robeson’s talent was undeniable. He was twice named to the All-American team—an extraordinary achievement made all the more impressive by the rampant racism he faced.2 Teammates and opponents often targeted him with brutal, racially motivated attacks, but he played through them with a quiet determination that would come to define his public life.

But Robeson wasn’t just an athlete. He excelled in debate and oratory, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1919. He went on to earn a law degree from Columbia Law School, though his legal career was short-lived after he encountered racial discrimination at a New York law firm.3 This disappointment would lead him to the stage.

A Voice on Stage and Screen

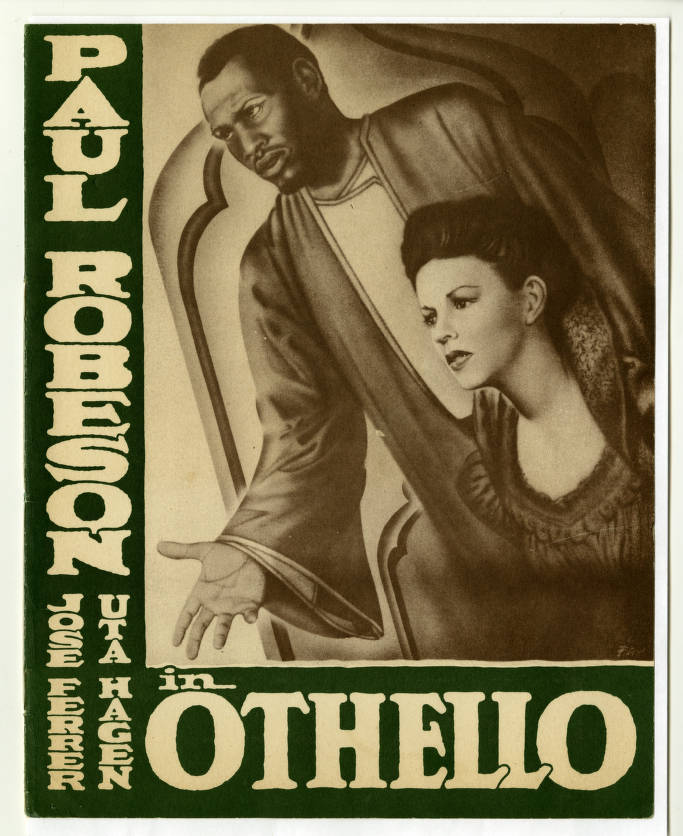

In the 1920s, Robeson began acting professionally, quickly gaining acclaim for his commanding stage presence and deep baritone voice. He brought a quiet dignity and intellectual force to his performances that audiences and critics couldn’t ignore. His breakout role came in 1924 in the play All God’s Chillun Got Wings, followed by The Emperor Jones and the musical Show Boat, in which his rendition of “Ol’ Man River” became iconic—an anthem of both sorrow and strength.

Robeson’s theatrical career flourished in the United States and abroad. In the 1930s, he moved to London, where he performed in Othello, becoming one of the first Black actors in the 20th century to play the title role in a major production. His performances brought him widespread acclaim, but Robeson’s interest in art was never separate from his commitment to justice.

As he traveled the world, Robeson used his platform to speak out against colonialism, fascism, and racism. He visited Spain during its civil war, lending moral and material support to the anti-fascist Loyalists. He embraced socialism and saw in it a possible antidote to the global exploitation of people of color. These views brought him into increasingly direct conflict with the U.S. government and mainstream media during the height of the Cold War.

The Cost of Conscience

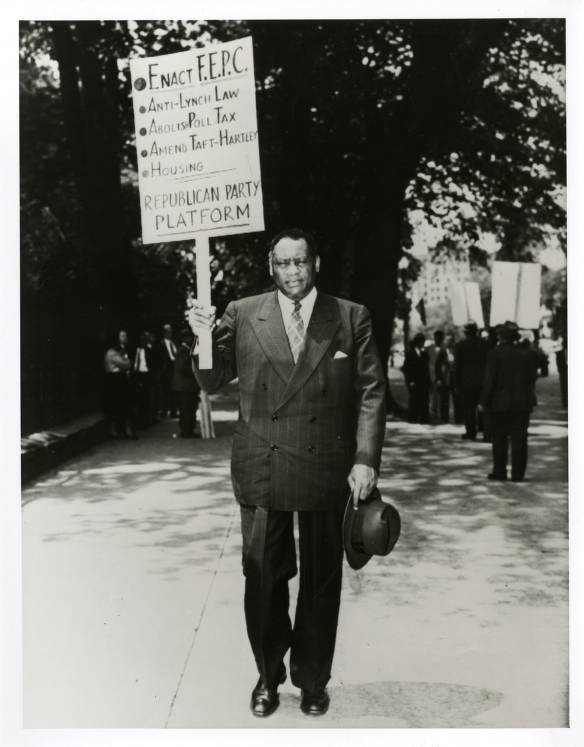

Robeson’s political beliefs were as courageous as they were controversial. He spoke out not only against racism in the United States but also against colonialism in Africa and Asia, and he openly admired the Soviet Union’s efforts to eliminate racial prejudice—though he remained silent on some of the regime’s atrocities. His refusal to renounce his views or to name others before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) placed him in the crosshairs of anti-Communist crusaders.

In 1950, the U.S. State Department revoked Robeson’s passport, citing his alleged Communist sympathies and “un-American activities.” This move effectively silenced his international career. He was unable to perform abroad or attend international peace conferences, cutting him off from audiences that had once embraced him.

before the United States Supreme Court restored it to him. (source)

Despite the professional and personal toll, Robeson remained defiant. He performed where he could—churches, labor halls, small venues—and continued to speak out against injustice. His passport was finally restored in 1958 after a protracted legal battle, a partial vindication of his rights as an American citizen.

Legacy and Recognition

The final decades of Robeson’s life were marked by a retreat from public life, brought on in part by health problems and the emotional weight of years of political persecution. He died in 1976 in Philadelphia, largely estranged from the country that had once both celebrated and vilified him.

Yet in the years since his death, Robeson’s legacy has grown. He is now remembered as a visionary artist and a courageous activist whose talents were matched by his moral clarity. Institutions have honored him with awards and memorials, and younger generations continue to rediscover his story.

Robeson’s life defies easy summaries. He was a scholar and an athlete, an artist and a political thinker. He believed, deeply and without apology, that art must serve the people—and that the artist has a responsibility to speak the truth. “The artist must take sides,” he once said. “He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery.”4

Paul Robeson chose freedom—again and again, even when it cost him dearly. And for that, his voice still resonates.

Suggested Reading:

Boyle, Sheila Tully. Paul Robeson: The Years of Promise and Achievement. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991025876699703811

Brown, Lloyd. The Young Paul Robeson. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1997. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991036523949703811

Duberman, Martin. Paul Robeson. New York: Knopf, 1988. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991024713969703811

Robeson, Paul. Here I Stand. London: D Dobson, 1958. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991032709649703811

By Dan Maguire

- Duberman, Martin. Paul Robeson. New York: Knopf, 1988. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991024713969703811 p. 11 ↩︎

- Brown, Lloyd. The Young Paul Robeson. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1997. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991036523949703811 p.68–70 ↩︎

- Boyle, Sheila Tully. Paul Robeson: The Years of Promise and Achievement. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991025876699703811 p. 111–114 ↩︎

- Brown 1997, p. 77 ↩︎