Beyond the Notes presents

Beyond the Notes: Hopper Haiku

Wednesday, February 5th, 2025, 12:00 PM

Charles Library Event Space

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged.

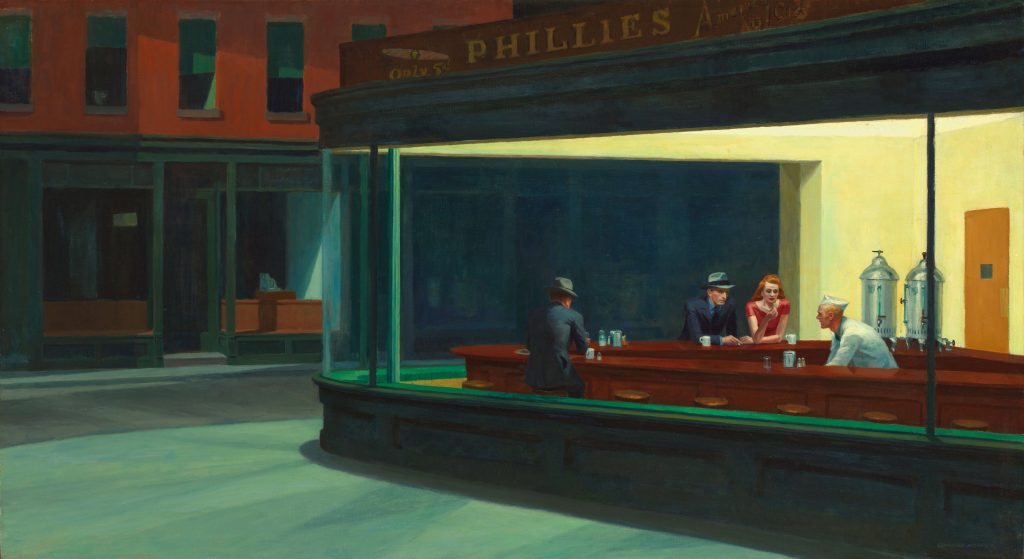

This month, Beyond the Notes will be featuring HOPPER HAIKU, a new art song project by composer/pianist Ellen Mandel and lyricist/baritone Daniel Neer, inspired by the artwork of American realist painter Edward Hopper. In honor of this new work, we will explore some other musical works inspired by visual art. The relationship between music and visual art is a fascinating one, as each medium seeks to evoke emotion, tell stories, and capture the essence of human experience. When one form of art describes or responds to another, this is known as ekphrasis. Most often seen in literature where writers vividly depict paintings, sculptures, or other visual works, ekphrasis is a way to bring artwork to life through words, helping the audience imagine its details, emotions, or meaning. In musical ekphrasis, composers translate visual art into sound using melodies, harmonies, and rhythms to capture the mood, movement, or essence of an artwork. This allows listeners to experience a painting or sculpture in a new way, as music transforms colors, shapes, and emotions into an auditory form. In this blog post, we explore five classical works inspired by specific artworks: Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Debussy’s Nocturnes, Rachmaninoff’s Isle of the Dead, Feldman’s Rothko Chapel, and Andriessen’s De Stijl. These pieces translate the static beauty of visual art into dynamic sonic landscapes, inviting listeners into a multi-sensory experience.

Mussorgsky – Pictures at an Exhibition (1874)

One of the most well-known examples of music inspired by visual art, Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition was composed in honor of his late friend, Viktor Hartmann, an artist and architect. Following his sudden death from an aneurysm at the age of 39, an exhibition of Hartmann’s works was held. Mussorgsky attended and was moved to create a suite of piano pieces, each depicting a different artwork.

The suite begins with the recurring Promenade theme, representing Mussorgsky walking through the exhibition. Each movement paints a vivid musical portrait: The Gnome, a grotesque, lurching figure; The Old Castle, evoking medieval nostalgia with its plaintive saxophone melody (in Ravel’s later orchestration); and The Great Gate of Kyiv, a triumphant finale inspired by Hartmann’s design for a city gate. The piece captures not just the imagery but also the emotions and narratives within Hartmann’s works, making it a masterpiece of musical ekphrasis.

Debussy – Nocturnes (1899)

Claude Debussy’s Nocturnes was influenced by the paintings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, particularly his Nocturne series. Traditionally used in music to describe dreamy, lyrical compositions evoking the night, Nocturne suited Whistler’s soft, tonal landscapes, which depicted twilight or nighttime scenes with subtle gradations of color and light. Debussy sought to achieve a similar effect in music, using shifting harmonies, ethereal textures, and delicate orchestration to capture the essence of fleeting moments.

The first movement, Nuages (Clouds), suggests the slow drifting of clouds across the sky, with its soft, muted colors and gentle motion. Fêtes (Festivals), by contrast, is vibrant and energetic, evoking the excitement of a nighttime celebration. The final movement, Sirènes (Sirens), features a wordless female choir, creating an otherworldly, seductive soundscape reminiscent of mythical sirens luring sailors to their doom. Debussy’s Nocturnes transform Whistler’s visual impressions into a richly textured auditory experience.

Rachmaninoff – Isle of the Dead (1908)

Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Isle of the Dead was directly inspired by a painting of the same name by Swiss symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin. Böcklin created several versions of Isle of the Dead, depicting a dark, mysterious island with a lone boatman ferrying a coffin to its shore. The image exudes a haunting stillness, a meditation on mortality and the afterlife. Interestingly, the version of the painting that inspired Rachmaninoff was not the original color painting, but a black and white reproduction. After seeing the original, he said “If I had seen first the original, I, probably, would have not written my Isle of the Dead. I like it in black and white.”1

Rachmaninoff translates this eerie vision into music through a hypnotic 5/8 rhythm, mimicking the slow, steady motion of oars rowing across water. The piece builds in intensity, evoking the island’s looming presence and the existential weight of the journey. The somber, brooding theme is later transformed into a grand, sweeping climax before returning to the quiet inevitability of the boat’s approach. In Isle of the Dead, Rachmaninoff masterfully captures the painting’s atmosphere of mystery and finality.

Morton Feldman – Rothko Chapel (1971)

Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel is an ambient, introspective work composed for the non-denominational Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, which houses a series of abstract, meditative paintings by Mark Rothko. Sadly, after completing the 14 paintings for the chapel in 1970, Rothko committed suicide. Feldman, a friend of Rothko who was deeply moved by the painter’s minimalist aesthetic, was asked to create a musical counterpart. The work was premiered in the octagonal chapel in April, 1972.

The piece is sparse, contemplative, and deeply atmospheric, mirroring the subdued yet emotionally charged nature of Rothko’s canvases. Feldman employs soft percussion, hushed strings, and choral passages to evoke a sense of space and reverence. The music unfolds slowly, with subtle shifts in texture and tone that reflect the way Rothko’s paintings encourage prolonged viewing and introspection. Rothko Chapel is less about melody and more about experience, an immersive soundscape that invites deep reflection.

Louis Andriessen – De Stijl (1985)

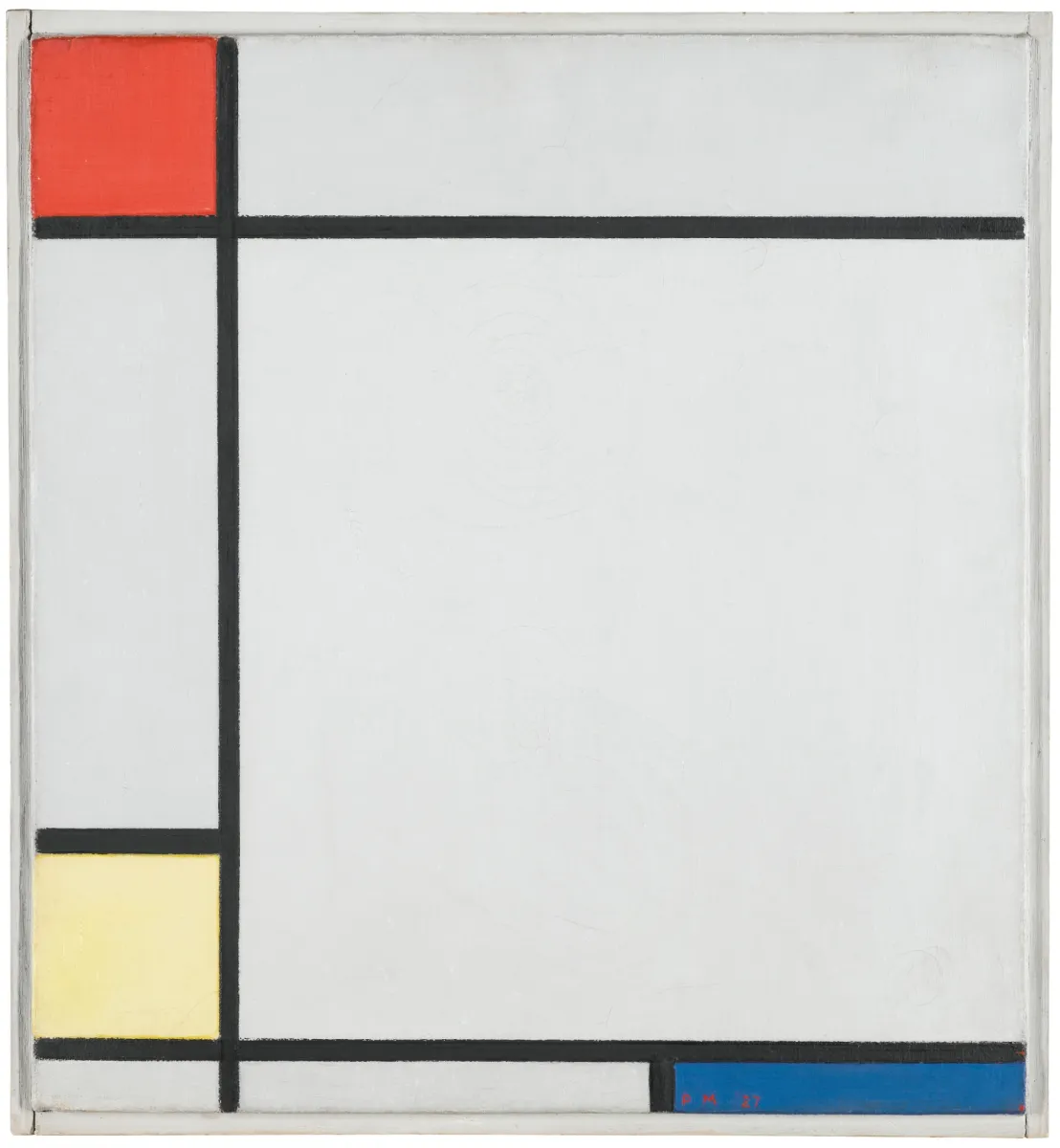

Dutch composer Louis Andriessen’s De Stijl is a tribute to the Dutch artistic movement of the same name, particularly the work of Piet Mondrian. Mondrian’s paintings, with their strict geometric arrangements of black lines and primary-colored rectangles, epitomize the movement’s principles of abstraction and order. Part three of a four part work known as De Materie, Andriessen described the piece as “a musical image of Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue from 1927, but exclusively on a conceptual basis.”

Andriessen translates this visual style into music with rhythmic precision, repetitive structures, and bright, bold harmonies. The work is energetic and mechanistic, reflecting the mathematical clarity of Mondrian’s compositions. Pulsating rhythms and interlocking patterns create a sense of movement and form, much like the visual rhythm in Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue. De Stijl is an exhilarating fusion of modernist art and music, capturing the dynamic balance between structure and spontaneity.

Shifting Media, Shifting Meaning

The interplay between music and visual art has led to some of the most evocative compositions in classical music history. From Mussorgsky’s sonic depiction of a gallery walk to Rachmaninoff’s brooding meditation on death, from Debussy’s dreamlike impressions to Feldman’s immersive minimalism, and Andriessen’s rhythmic abstraction, each of these works demonstrates how composers have translated visual imagery into powerful musical statements. By listening to these pieces with their corresponding artworks in mind, we can appreciate the depth of inspiration that visual art has provided to music, creating a richer and more immersive artistic experience.

Suggested Reading:

Chong, Corrinne, and Michelle Foot, eds. Art, Music, and Mysticism at the Fin-de-Siècle: Seeing and Hearing the Beyond. New York, NY: Routledge, 2024. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991039090718203811

Coleman, Patrick, Simon Shaw-Miller, Richard D. Leppert, Sandra Benito, Michael A. Brown, Patrick Coleman, Anita Feldman, et al., eds. The Art of Music. San Diego: San Diego Museum of Art, 2015. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991012394889703811

Dohoney, Ryan. Saving Abstraction: Morton Feldman, the de Menils, and the Rothko Chapel. Oxford Scholarship Online. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991037759605603811

Eisen, Cliff, and Alan Davison. Late Eighteenth-Century Music and Visual Culture. Music and Visual Cultures, volume 1. Turnhout: Brepols, 2017. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991036937650403811

Elkoshi, Rivka, Gila Russo-Zimet, and Dorit Cohen. Rainbow Inspirations in Art. Fine Arts, Music and Literature. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated, 2017. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991039016130803811

Junod, Philippe, and Saskia Brown. Counterpoints: Dialogues between Music and the Visual Arts. London, UK: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2017. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991036865395903811

Leach, Brenda Lynne. Looking and Listening: Conversations between Modern Art and Music. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991006746699703811

Whitney, John. Digital Harmony: On the Complementarity of Music and Visual Art. Peterborough, N.H: Byte Books, 1980. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991010478029703811

By Dan Maguire

- Tarasti, Eero. Semiotics of Classical Music: How Mozart, Brahms and Wagner Talk to Us. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition [SCC] Ser, v. 10. Boston: De Gruyter, Inc, 2012. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991036745547203811 ↩︎