Beyond the Notes presents

Beyond the Notes: Charles Ives–American Iconoclast

Wednesday, October 23, 2024, 12:00 PM

Charles Library Event Space

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged.

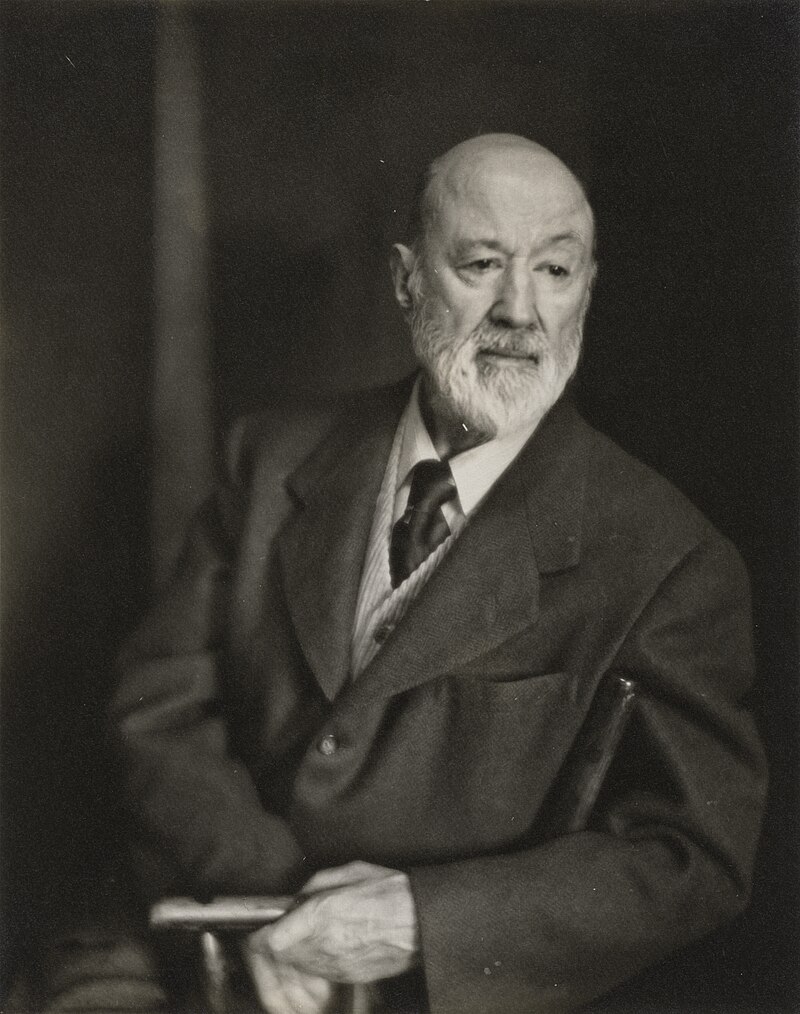

This month, we celebrate the 150th birthday of American composer and iconoclast Charles Ives (October 20, 1874–May 19, 1954). Best known for works such as his Symphony No. 4, which requires two conductors and incorporates such well-known hymns as “Bethany” (“Nearer, My God, to Thee”) and “In the Sweet By-and-By,” his “Concord” Piano Sonata No. 2, based on his fascination with the New England Transcendentalists, and his powerfully stark “The Unanswered Question,” which pits a babbling chorus of woodwinds against a nearly static background of strings while a solo trumpet repeatedly intones the eponymous “question,” Ives’s music defies simple description. Young Charlie was inspired by his Connecticut band-leader father, who challenged him to hear music and beauty in all sounds. In an oft-quoted passage, Ives described some of the musical experimentation his father introduced him to:

“[My Father] would occasionally have us sing, for instance, a tune like The Swanee River in the key of Eb, but play the accompaniment in the key of C. This was to stretch our ears and strengthen our musical minds, so that they could learn to use and translate things that might be used and translated (in the art of music) more than they had been. In this instance, I don’t think he had the possibility of polytonality in composition in mind, as much as to encourage the use of ears—and for them and the mind to think for themselves and be more independent—in other words, not to be too dependent upon customs and habits.”1

Ives created music unlike anything that anyone else was writing at the turn of the 20th century, but even more astonishingly, he did so while carrying on a career in business. His musical life remained more or less private until the 1930s, when his music finally started to be performed. In this post we consider Ives, not as the composer, but as the businessman and insurance executive who scribbled down musical ideas in his office and composed symphonies and art songs on the weekends, in order to understand how Ives’s creative life intersected with his professional one. Art and business, Ives believed, were not so very dissimilar as we might think them to be.

Why did Ives not become a professional musician? As an undergraduate at Yale, he studied under Horatio Parker, one of the most well-known American composers of the late 19th century, and early in his career young Charlie served as a church organist and choir director at First Presbyterian Church in Bloomfield, New Jersey, and later at Central Presbyterian Church in New York City. But Ives knew the life of a professional composer would be a challenge for him. His father’s example had shown him the precarity of a musician’s livelihood. Furthermore Parker’s reactions to the kind of challenging, experimental music he wrote as a student had confirmed to him that as a professional composer, he would be forced either to fall in with current trends and tastes, or to starve. Unwilling to compromise his artistic vision, he realized that only by remaining an accomplished “amateur” could he create music as he wanted.

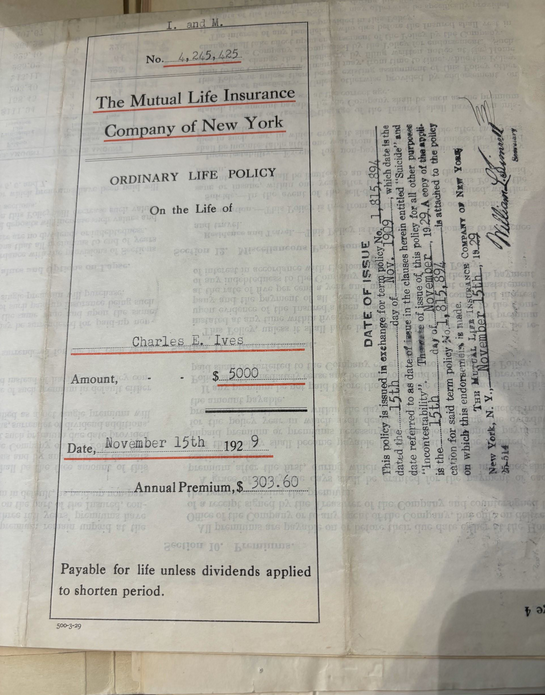

And so Ives began working at the Mutual Life Insurance Company in New York City as an actuary. He lived with a group of other young men in a building known as Poverty Flat, where he was popular and had time to go to night school, pitch on his agency’s baseball team, and of course, write music. Eventually, he met Julian Southall Myrick, known commonly as “Mike,” who became a lifelong friend and business partner. The insurance company they opened in 1907, which eventually would be called “Ives & Myrick,” would provide Ives not only with a successful livelihood as he continued his composing in private, but also with an outlet for his strongly humanistic tendencies. For Ives, insurance wasn’t simply a way to make money, but also a way to help his fellow man.

Ives’s concern with helping others realize their own financial security comes across clearly in the role he took on at Ives & Myrick. While Myrick ran the business side of the company, Ives specialized in the training of insurance agents. He developed teaching materials, pamphlets, and courses to train salesmen and agents how best to approach the selling of life insurance. It was important to Ives that all men, no matter their station in life, understand the importance of planning for their family’s financial future. As Myrick later told Vivian Perlis in her oral history of Charles Ives, “He had a great conception of the life insurance business and what it could and should do, and he had a very powerful way of expressing it. He did a great deal of writing, much of it published and widely used.”2 One of his former clerks, Charles J. Buesing, told Perlis,

“Mr. Ives was way ahead of his time in teaching young men like me and older established salesmen something about a more professional approach in the selling of life insurance, instead of just selling a policy just because a policy was a good thing to have. He came up with a plan. By measuring the economic value of a man to his wife and children, and translating that into an amount of insurance within the man’s ability to pay, we got, at long last, away from policy pedlars [sic] into a science.”3

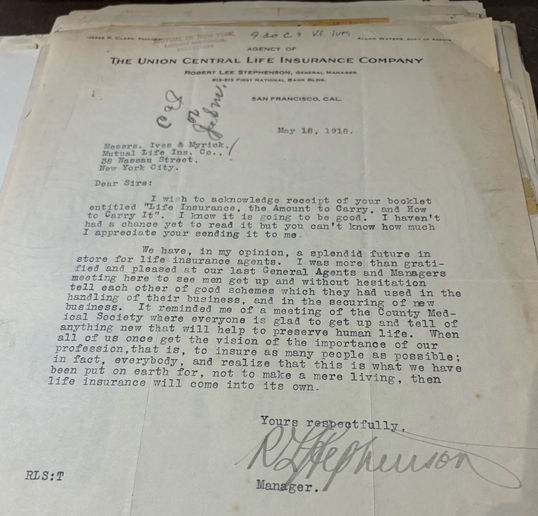

Ives codified his approach in a 1910 pamphlet called Life Insurance: The Amount to Carry and How to Carry It, a seemingly ephemeral work that would help form the basis of modern estate planning. The records left behind by Ives & Myrick, now held at Yale University in the AXA Equitable Life Insurance Company Papers Related to Charles Ives, contain dozens of letters from representatives of other insurance agencies requesting copies of Ives’s teaching materials, as well as letters of thanks, such as the one below from the general manager of the Union Central Life Insurance Company of San Francisco.

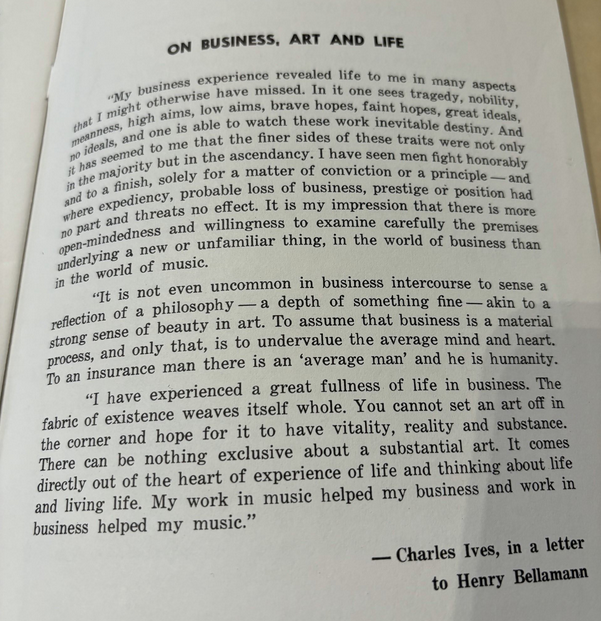

Throughout all the writings of Ives’s contemporaries, the theme of his concern for his fellow man and how that drove his business acumen persists. A concert program held in remembrance of Ives’s 85th birthday in 1959, five years after his death, printed an excerpt from a letter Ives wrote to Henry Bellamann, a friend and popular novelist of the time: “My business experience revealed life to me in many aspects that I might otherwise have missed. In it, one sees tragedy, nobility, meanness, high aims, low aims, too brave hopes, faint hopes, great ideals, no ideals, and one is thus able to watch these forces work inevitable destiny” (see below). As Myrick told Perlis, “Ives’s contribution to the business was very great, and he worked continuously to improve it. He felt that the protection of the family and the home was a great mission.”4

In his music and in business, Ives was a great democratizer. He felt music should be for and represent all people and humanity, from a young boy’s excitement during a Fourth of July parade to the imagined ascension to heaven of the founder of the Salvation army. His music communicates seemingly inexpressible ideas and feelings in ways more direct and daring than any of his contemporaries would have dreamed. As Perlis wrote:

“He believed that men should communicate directly with each other on a personal basis, one to one. In his music, one finds this sense of immediacy, of communicating almost intangible experiences; his political beliefs depended on getting rid of the politician’s standing between people; his insurance teachings were based on the insurance salesman’s determining the right kind of policy for each client’s individual needs. This idealism extended to a deep concern for the common man–Ives devised policies small enough so that insurance would be available for the workingman and his family.”5

Listen, for example, to the recording of the “Fourth of July” movement from A Symphony: New England Holidays linked above. In just over five minutes, Ives paints a picture, not through formalistic structures or traditional harmonic development, but through the building of sound and tension from amorphous sounds and gestures to a glorious cacophony of patriotic sentiment, as numerous marching bands pass by our wonderstruck protagonist while he watches and listens from the parade sidelines. In the “Alcotts” movement from his “Concord” Piano Sonata, a child in the family of famed reformer and educator Bronson Alcott–perhaps young Louisa May herself, years before achieving fame as the author of Little Women–seems to become distracted and carried away while improvising on the opening notes of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5.

Ives’s direct expression, willingness to create outside of accepted modes of composition, and deep affection for humanity at all its levels are echoed in his legacy as an innovator and educator of the selling of life insurance. We hope you’ll join us on October 23 for this celebration of the music of Charles Ives!

- Stuart Feder, Charles Ives, “My Father’s Song” : A Psychoanalytic Biography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 115, quoting from Yale University Music Library Archival Collection, MSS 14, New Haven, Connecticut, January 1983. ↩︎

- Vivian Perlis, Charles Ives Remembered (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974), 36. ↩︎

- Ibid., 65. ↩︎

- Ibid., 36. ↩︎

- Ibid., 45-46. ↩︎

Suggested Reading:

Burkholder, J. Peter, ed. Charles Ives and His World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991035827779703811.

Feder, Stuart. Charles Ives, “My Father’s Song” : A Psychoanalytic Biography. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991029405089703811.

Magee, Gayle Sherwood. Charles Ives : A Guide to Research. New York: Routledge, 2002. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991030023619703811.

Magee, Gayle Sherwood. Charles Ives Reconsidered. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991030062739703811.

Owens, Tom, C., ed. Selected Correspondence of Charles Ives. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2007. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991036732270003811.

Perlis, Vivian. Charles Ives Remembered; An Oral History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974. https://librarysearch.temple.edu/catalog/991002214899703811.