As the 2024 Paris Olympic Games race towards their exciting conclusion, viewers across the world are learning about sports they’ve never heard of and rooting for athletes who have become household names overnight. But one detail of the Olympics receives little attention despite its crucial significance to numerous sports and disciplines.

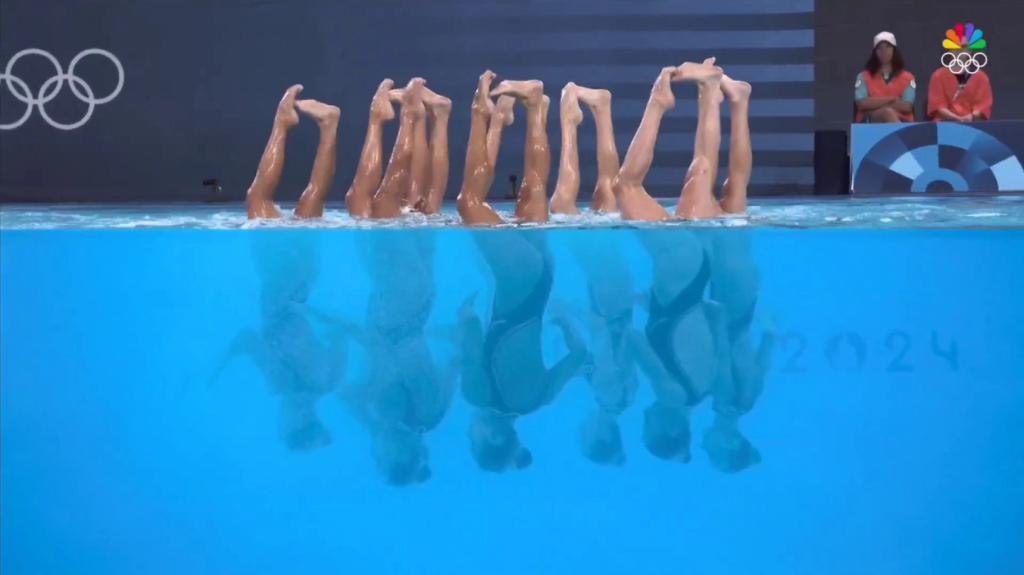

Simone Biles famously tumbled to an all-around gold to Taylor Swift’s and Beyoncé’s music for her floor routine, with her teammates Suni Lee and Jordan Chiles choosing Lindsey Stirling and Beyoncé, respectively. The US artistic swimming team went viral for dancing an upside-down underwater moonwalk to Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal,” while the Mexican team paid tribute to the rock band Queen. And viewers watching various arena sports have heard music by the White Stripes, Chappell Roan, Los Del Rio, Sia, and Gioacchino Rossini, among many others, punctuating the cheers of the crowds. So ubiquitous is such background music, or the music that accompanies artistic gymnasts and swimmers, not to mention the figure skaters and ice dancers of the Winter Olympics, that most of us don’t even question the legality of such uses of music.

But as it turns out, getting permission to use popular song recordings at the Olympics is a big deal! Before a gymnast can legally execute a wolf turn in their floor routine or a figure skater can attempt a triple Axel to the accompaniment of their favorite copyrighted music, permissions must be granted, or licensing must be purchased, in order not to run afoul of copyright law.

Why is copyright at the Olympics a big deal?

You might be asking yourself, “Why does anyone care about music played at sporting events? It’s not like Simone Biles is making money off Taylor Swift’s or Beyoncé’s music. Is the estate of Michael Jackson really being harmed if an artistic swimming team uses his music in their routine?” It’s important to understand the rights that copyright holders have over the performance or use of their intellectual property, and how that relates to public sporting events.

There are five rights granted to owners of copyrighted works:

- The right to reproduce the work

- The right to prepare derivative works

- The right to produce and distribute copies

- The right to publicly perform the work

- The right to display the copyrighted material

This means anyone who wants to play a recording of copyrighted music in a public context, with some exceptions, must first obtain permission.

On top of these rights, there is another complication to how copyright works for music. Recorded music is subject to two different types of copyright:

- Copyright of the musical composition (the notes and lyrics that can be written down),

- and copyright of the specific recording in question.

This means that even if a song has entered the public domain—meaning it is no longer subject to copyright restrictions and can be used freely—a new recording of that song is still subject to copyright law and needs to be lawfully licensed by anyone who wants to reproduce, derive a new work, distribute copies of, publicly perform, or display the work in question.

What does this mean for the Olympics? Before playing any copyrighted musical recording in a public performance setting, a license must be obtained from the copyright holder or organization that manages the licensing of copyrighted IP. The licenses ensure that the creator of the musical work receives royalties from the use of their creation. A number of different types of licenses are available depending on how the IP is being used, but the two most relevant to this case are blanket licenses and synchronization licenses.

When you hear a copyrighted song used in a TV show, commercial, or film, the creators of that filmed work needed to obtain a synchronization license to use the music lawfully. Synchronization licenses grant permission to use or reproduce music in the context of a filmed production meant to be shown at a later time, such as in a movie theater or on a streaming platform. A blanket license, on the other hand, grants the right to use a song or a catalog of music for a set period of time. Blanket licenses are what allow radio stations, restaurants, and other businesses that depend on large music playlists and catalogs to legally play or broadcast musical recordings. This type of license also applies to live events such as the Olympics, meaning NBC, which broadcasts the Olympics in the United States, pays a blanket fee for all the songs to be used in the games rather than a separate synchronization license for each song.

But wait!, you might be asking. The Olympic events are recorded and made available to be streamed both live and on demand on platforms such as Peacock, and NBC and other networks replay clips later on separate broadcasts. Furthermore, attendees create their own videos that get posted on social media, further complicating the status of the music played at the Olympics games. Like many issues of copyright, it won’t be fully known how exactly the legality of these reproductions of copyrighted music stand up to the licenses obtained by NBC until much later. Copyright law is often clarified and shaped by the lawsuits that result from potential infractions, as happened after the 2022 Winter Olympic games.

After U.S. silver medalist pairs skaters Brandon Frazier and Alexa Knierim used the Heavy Young Heathens’ cover of “House of the Rising Sun” in their short program, Robert and Aron Marderosian, the musician brothers behind the Heavy Young Heathens, sued the skaters, Comcast Corporation, NBC Universal Media, U.S. Figure Skating, and others for copyright infringement. The problem seemed to lie in a simple misunderstanding of copyright law: remember the two different elements of a musical recording that are protected by copyright—the composition and the recording itself? While “House of the Rising Sun” is a public domain song that can be freely recorded or performed without the need for licensing, the recording by the Heavy Young Heathens is protected by that element of copyright law specific to recordings. The case was settled out of court and the details were not made public.

So how can present and future Olympians ensure that they don’t make the same mistakes that Frazier and Knierim made, and avoid potentially costly lawsuits? The IOC, the organization responsible for putting on the Olympics and Paralympics, provides freely accessible information to help make this confusing process easier and more painless. The Olympics website provides access to an informational video explaining copyright for “Music in Sport,” and a separate handbook, “Music in Sport—Guidance for Athletes,” provides even more information, including a list of Collective Management Organizations by territory to help athletes from different countries determine how to obtain performance licenses. And you don’t need to be an Olympian to learn how to use music responsibly! The National Federation of State High School Organizations provides their own guide to Copyright Compliance with Music and Sporting Events to help high schools use music responsibly at their sporting events. Did you know that a high school pep band doesn’t require permission from the copyright owner to play copyrighted music at a sporting event? You do now!

Learn more about copyright by visiting Copyright: A Guide to the Law and Fair Use through Temple Libraries!

Learn about music and copyright at Temple University Libraries:

Further reading about music, dance, sports, and copyright: