Beyond the Notes presents

A Visual Music Sampler

Wednesday, January 31, 2024, 12:00 PM

Charles Library Event Space

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged.

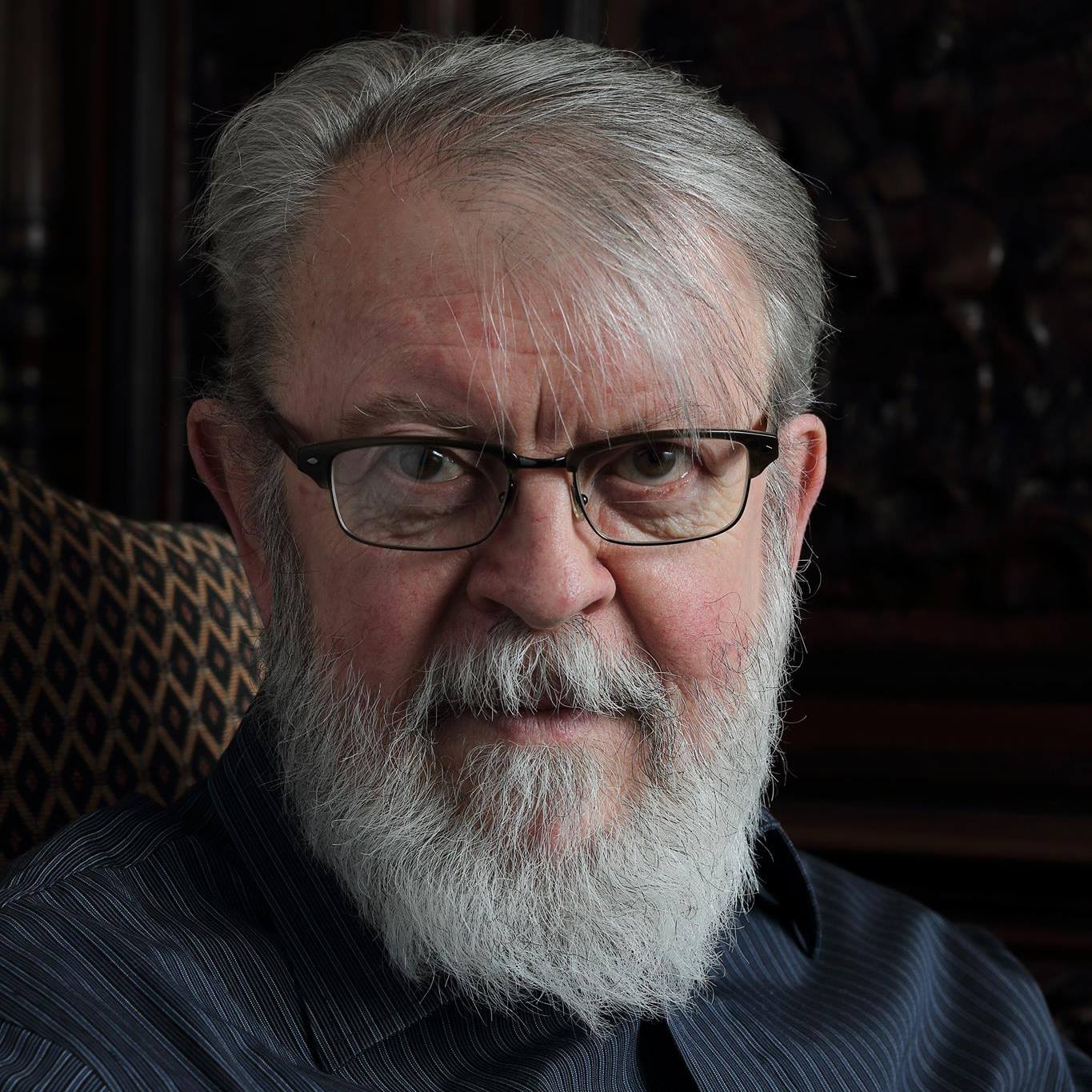

Join Boyer Professor of Music and composer Maurice Wright in a presentation of electronic music, live performance, and the marriage of music and visuals. Professor Wright explains how he first came to create video counterparts for his electronic music, and how his fascination with images began to lead his imagination to grander schemes. Along with compositions for computer sound and projected video, flutist (and Beyond the Notes alum) Chelsea Meynig will perform PHOENIX, a work in which they collaborated via Zoom during the pandemic. In anticipation of this concert, I conducted an interview with Professor Wright to gain some insight into his background and creative approach. The following interview was edited for clarity and length.

Dan Maguire: You have explored a number of different specialties throughout your musical life, including piano, trombone, and many different electronic devices – can you tell us about these different facets of your musical background and how you decided to focus on composition?

Maurice Wright: Well musically there are a lot of things I did because I like making music, but composition has been the thread that runs through them. I took piano lessons and I didn’t like practicing as much as I did just seeing the notes and so forth and so I started skipping the piano lessons and would write music down and play it myself.

And so composing is the thread that runs through all of it. I also had a really fun interest in experimenting with electrical things. There were dry cell batteries from old telephones — so you couldn’t really hurt yourself — but they were powerful enough to drive microphones and handsets. The microphones were carbon granule, you know, like a variable resistance. And if you hooked that across the voltage and ran the wire and hooked an earpiece across it and then on the other end, you could make a telephone.

Now the problem as a kid playing on his own was you couldn’t really run outside to see whether it worked. You’d have to find a really busy older relative to listen to the other end. But it was a lot of fun to do that. And it got me interested in circuits and physics and magnets. All that stuff kind of goes together. And then eventually, sometime in elementary school, I guess, experimenting with a tape recorder. And that was fun too, playing sounds forwards and backwards. And in high school computers were just kind of becoming a thing.

DM: Much of your work features visual elements – can you speak on what about visual material you find particularly inspiring or challenging to work with?

MW: I went to Columbia and was really interested in electronic music, and loved doing electronic music, and felt that a shortcoming in our concerts was the visual aspect. You could write a piece with a performer with that posed a whole set of problems that were kind of restrictive in the lab. In the lab, you could deal with the tiniest details of a phasing and reverberation and crazy timings. But once a performer got involved, you were starting to have to approximate everything. You have to fit it to what the performer can do.

source: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/computinghistory/cpemc.html

And it took away an aspect in some ways. So I was thinking about things that would work to make images or to make to make something visually interesting for concerts. And after a series of missteps and other things that came upon the notion of adding graphics to it, video editing software became available. Adobe Premiere was kind of clunky to use, but nevertheless it worked. If you could get a sequence of images, you could make them into a to a movie file and you could synchronize it with sound.

DM: There were a couple other alternative ideas before you arrived at graphics, right, for what the audience could look at?

MW: Yeah, one was the idea of a building in which there no one can see the stage and every seat had an obstructed view, so you would have to imagine what was happening on a stage that you couldn’t see. There might be something Platonic in that. And the other idea was one where the hall is split in half and an audience sits on either side looking — staring — at one another during the concert.

DM: But there’s probably still a project in one of those ideas.

MW: Yes, some audience members might be, uncomfortable with that. It’s fun, the question about doing that. But, you know, I’m not an architect and we’re talking about setting something up for a concert. So really what people do know how to do is to watch a screen and accept pretty much whatever the sound is that comes from that. I read this morning that the Philadelphia Orchestra have even more emphasis on film music next year than this year. And I don’t think that’s because the orchestra isn’t interesting to watch or that the film music is somehow better than the repertoire.

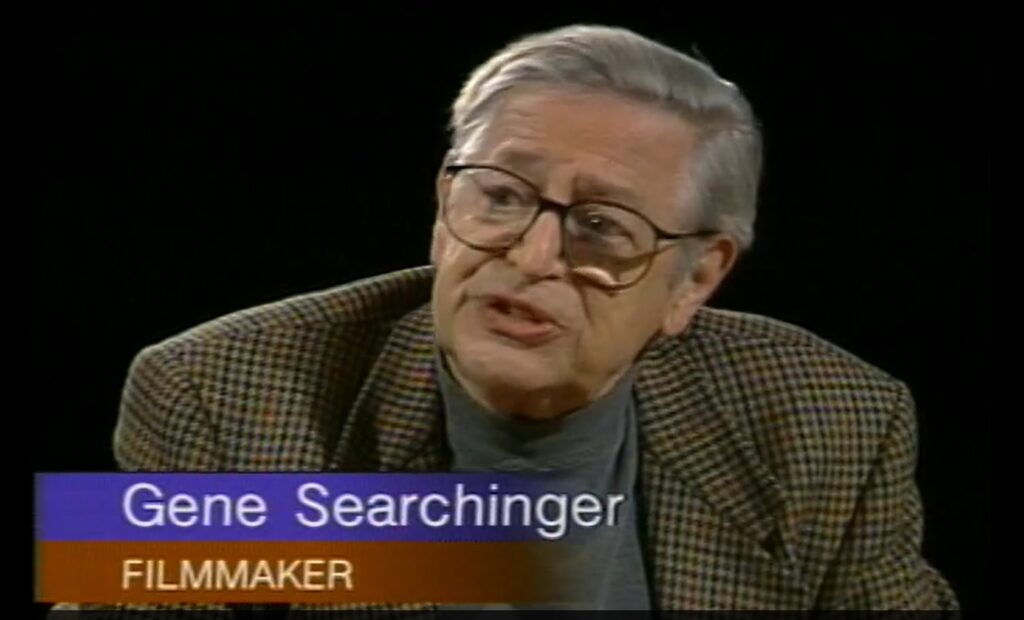

But for some reason, that’s a thing that draws people. And I have worked with a documentary producer in New York, Gene Searchinger. We did one film for the Metropolitan Museum of Art that Caroline Kennedy produced. Another was a three part series about linguistics, about the human language and how it is that we come to speak to each other. And in all of that I learned that movies were not the kind of orderly progression from script to image that I thought they were, but really more of a business of looking through images for connections and starting with a large library of stuff and culling it down. And the way I jumped to do that with music, other than some early kind of cartoonish experiments was to find ways to actually visualize the sound and to use samples on the sound file to make patterns on the screen, not oscilloscopic, but through a technique called Delta encoding, which is used by the researchers that study strange attractors and chaos theory, where you can use the difference between samples to plot X and Y positions. And if it’s periodic, you get some sort of circular thing. If it’s purely random, you get a diagonal line, depending how you’ve mapped it. And if it’s something in between, you get an image in between.

DM: So without spoiling too much for the audience, could you say a little bit about each of the pieces that we’re going to be seeing?

MW: They’re in chronological order, so it starts way back, I think in the 90s, and then works its way through to 2022. And the first and what you might mainly see is how display technology and computers got better: more dots were on the screen. Memory became cheap, hard drives fantastically better and cheaper than they were.

And so the first piece, Seven Cartoons is part of a longer piece that I wrote on commission from Network for New Music, which has four cycles of movements and opens with a duo for piano and saxophone. I then took the same notes from that and realized them using a computer language. I was learning to use Csound at the time and this was sort of an etude to learn how to use Csound. So I programmed those pieces and then created video for them that were pretty much cartoons. Two-dimensional figures that get put together and sliced together, but very flat, kind of some movements very jerky, probably inspired as much by Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python opening sequences as anything. He was really clever at taking cutouts and moving them, slightly — stop action motion with cutouts to make these things. And I kind of just played with that.

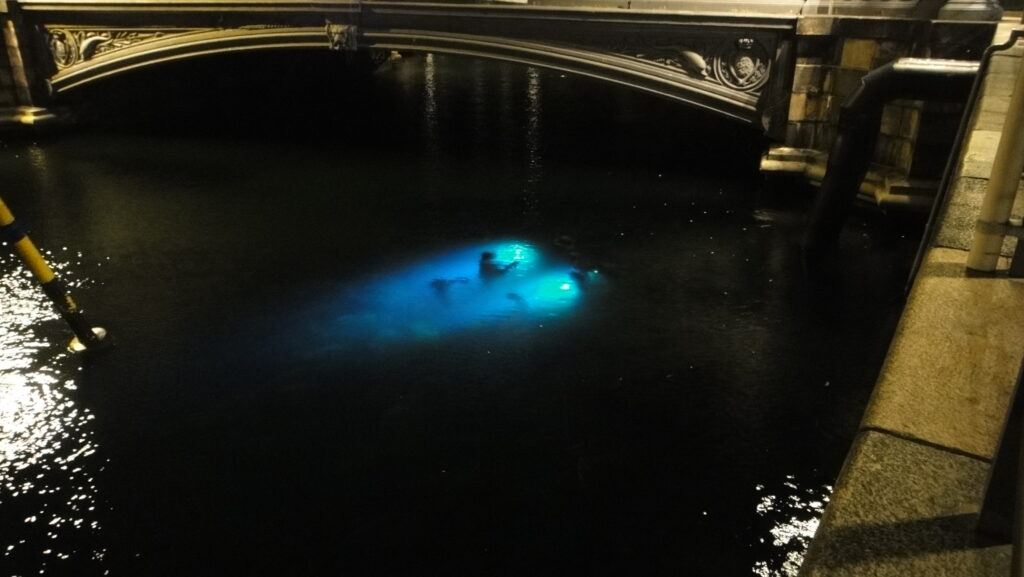

The second piece is short. It’s called A Fish’s Tale. It was composed for the International Computer Music Conference, which had a theme for its convention in Copenhagen. And the theme was music underwater. Because they were very proud of all the waterways around Copenhagen. Each one now was clear enough to swim in and to see through. And so the city commissioned a bunch of big statues under the water so you could go to a canal, stand on the bridge and look down and see a statue looking up at you.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Agnete_and_the_Merman_sculptures.JPG

And this was the theme of the conference. And so I thought I would try to do a thematic related piece. It’s about waters rising and everything being under the water. And somehow the fish, because of all the disruption, contract some awful virus that the ones that survive end up with capacity for speech. And consequently, broadcast companies find ways to tailor entertainment for fish to watch.

Then the next piece, Domestic Tranquility, is long. It’s 28 minutes. So that’s almost TV length. It’s done in two parts. And the entire long thing was shown, screened a couple of times at conferences, but too long for most of them. It is based on a theme of the dangers of misinformation. It has to do with a man who believes what he hears on television and ends up destroying his environment and nearly getting killed himself before he sees the truth and is helped by the very things he was trying to destroy.

The last one is short, but the most complicated in some ways in that it has a performer, so this kind of goes full circle to the beginning. This was composed during the pandemic in collaboration with Chelsea Meynig, whom I had met at Temple. Chelsea and I were in contact because she plays always for my orchestration classes. The orchestration classes were on Zoom, and she played the demonstration of the flute remotely. We thought this is really an awful time.

So we commiserated. And then a group that I know in New York called Association for Promotion of New Music sponsored a competition for a grant for pieces called The Masked Performer, where you would write a piece for a performer that could be performed solo during COVID so they wouldn’t infect anyone. But Chelsea and I decided we would do it as a piece which would collaborate and she would play the flute and I would do computer sound. Then I would do abstract video and I would also record her.

So there are various versions of the piece, some with her on video edited in to make a sequence, but there’s also a version with just the electronic sounds using the same technique I described as the really oldest one, the Delta encoding, which are projected right onto the flute player, it looks like a little fire burning inside and it turns into bird feathers as the phoenix takes off. The Phoenix, was her idea, it was a storytelling piece.

And so it’s not really the culmination of a sequence, but in terms of the evolution in time, you can see how the graphics became more of a tool that I could add to something as opposed to an end of a project. That’s kind of how it works. They’re very different though.

DM: You’ve been a fixture at Temple for many years. How does your role as an academic impact your approach to composition?

MW: Temple has been a great place. When I was a kid, living in Tampa, my family were not academics. There were five children and I was the only one to finish high school. But as a kid, I loved the university. I could ride my bicycle over to the University of South Florida. And they had practice rooms with grand pianos that the students apparently didn’t need, were great for me. I always got to play the piano. They even had a bookstore that sold music.

I found the library that had untouched volumes of music journals and scoresw. And it just seemed like the greatest place. I thought, you know, when I get older, I want to work in one of these places because it looked just like so much fun. I met astronomers who were setting up a planetarium. And I thought, wow, what do you have to do to do this? For me, it was enough to make me want to try to do well enough that I could go to college. The other thing that really inspired me to go to college was the jobs you get as a high schooler. You get to be a janitor. You get to do kind of anything that no one wants to do, a lot of it with a shovel. You know, it’s enough to make you want to work hard in school. So when I got to Temple, I thought, well, I have arrived, this will be so much fun.

And then I was kind of crushed by the workload. And it took me a long time to adjust to that. But the people, faculty, and students that I met along the way have really been wonderful musical partners. I came to Temple probably because my friend Lambert Orkis was on the search committee. He’s on our piano faculty still today. Lambert and I loved to see each other and to talk about music.

I was really happy to be where he was. And the students at Temple have always been, continue to be today, to be really stimulating and very interesting musicians. Mark-André Hamlin, the famous pianist, was a great composer, a composition student. Will Hudgins, now principal percussionist of the Boston Symphony, could be found in the basement of Presser Hall, practicing Porgy and Bess into the late hours. Linda Reichert, who started Network for New Music, was a composition student of mine for a time. Charles Abramovic, chair of our piano faculty, took some lessons. He’s a great player. And really throughout the time that I was there, it’s been fun. I think the most ambitious and experimental pieces I’ve put on at Temple, I once did an Opera with robots. You could do it there because the risk was so much lower than in any kind of professional setting and there were people who collaborate. So it was as much fun as I thought, but not in the way I thought it would be.

By Dan Maguire