Beyond the Notes presents

Songs of the People:

A Celebration of Women Composers from the African Diaspora

Wednesday, April 19, 2023, 12:00 PM

Charles Library Event Space

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

All programs are free and open to all, and registration is encouraged.

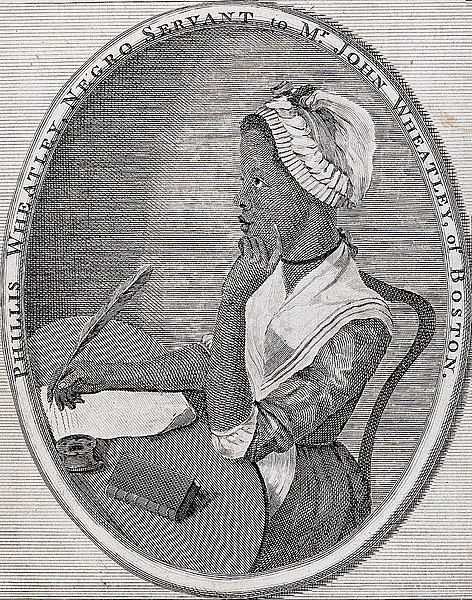

Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Sally Hemings…these names of famous Black women born into slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries are familiar to most Americans. Fewer are familiar with a woman who predated all of these women and who helped open doors to other Black and enslaved peoples as the first published poet of African descent in American history. Phillis Wheatley’s short but inspiring life and work inspired one of the works included in our upcoming program: Rosephanye Powell’s set of three art songs, Miss Wheatley’s Garden. But who was Phillis Wheatley?

Wheatley (c. 1753–1784) was born in western Africa—possibly in what is now Gambia or Senegal—but was kidnapped and sold into slavery at the age of 7 or 8. Transported to Boston, Massachusetts, she grew up as a domestic slave for the Wheatley family for the remainder of her adolescence through young adulthood. Not long into her time with the Wheatleys, however, the family recognized her extraordinary intellectual gifts and shifted her responsibilities from housework to her own education. With the help of her owners’ daughter, Mary, Wheatley learned to read and write, quickly developing an affinity for classical and religious literature.

The resources provided by the Wheatleys allowed a young Phillis to find her own voice through poetry. Wheatley published her first poem in 1767, making her the first published African-American woman. However, she faced significant challenges in her attempts to publish her works. At this time publishing was often done on a subscription basis, with readers putting up money in the form of a subscription to fund the publication of works they wished to support. The white, literate public refused to believe that an enslaved teenager from Africa was truly the author of her works. Eventually she faced a board of eighteen prominent Bostonian men in order to prove herself. When her poems were eventually published, her master John wrote a testimonial attesting to her talents that was published alongside a list of the men who sat in judgment of Phillis, which included Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson and John Hancock:

Phillis was brought from Africa to America, in the Year 1761, between Seven and Eight Years of Age. Without any Assistance from School Education, and by only what she was taught in the Family, she, in sixteen Months Time from her Arrival, attained the English Language, to which she was an utter Stranger before, to such a Degree, as to read any, the most difficult Parts of the Sacred Writings, to the great Astonishment of all who heard her.

As to her Writing, her own Curiosity led her to it; and this she learnt in so short a Time, that in the Year 1765, she wrote a Letter to the Rev. Mr. Occam, the Indian Minister, while in England.

She has a great Inclination to learn the Latin Tongue, and has made some Progress in it. This Relation is given by her Master who bought her, and with whom she now lives.

JOHN WHEATLEY[1]

![Printed title page from an antique book, it reads: "To the PUBLICK. As it has been repeatedly suggested to the Publisher, by Persons, who have seen the Manuscript, that Numbers would be ready to suspect they were not really the Writings of PHILLIS, he has procured the following Attestation, from the most respectable Characters in Boston, that none might have the least Ground for disputing their Original.

WE whose Names are under-written, do assure the World, that the Poems specified in the following Page, [asterisk] were (as we verily believe) written by Phillis, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been [unreadable], under the Disadvantage of serving as a Slave in a [unreadable] this Town. She has been examined by some of the best judges, and is thought qualified to write them.

His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Governor, The Hon. Andrew Oliver, Lieutenant-Governor, The Hon. Thomas Hubbard, The Hon. John Erving, The Hon. James Pitts, The Hon. Harrison Gray, The Hon. James Bowdoin, John Hancock, Esq; Joseph Green, Esq; Richard Carey, Esq; The Rev. Charles Chauncey, D. D., The Rev. Mather Byles, D. D., The Rev. Ed. Pemberton, D. D., The Rev. Andrew Elliot, D. D., The Rev. Samuel Cooper, D. D., The Rev. Mr. Samuel Mather, The Rev. Mr. John Moorhead, Mr. John Wheatley, her master.

N. B. The original Attestation, signed by the above Gentlemen, may be seen by applying to Archibald Bell, Bookseller, No. 8, Aldgate Street.

*The Words "following Page," allude to the Contents of the Manuscript Copy, which are wrote at the Back of the above Attention.](https://sites.temple.edu/performingartsnews/files/2023/04/Phillis-Wheatley-To-the-Publick.png)

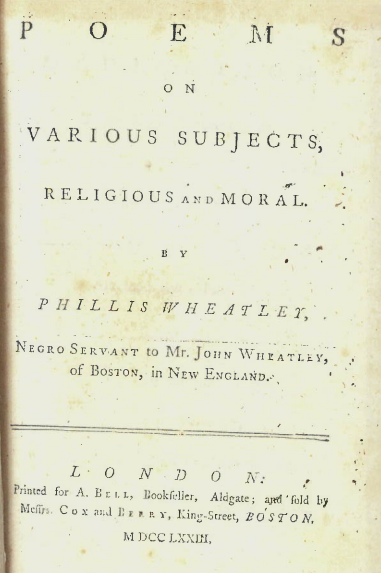

When this still did not gain her the subscribers she needed, her owner’s wife Susanna found her a potential patroness in the Countess of Huntingdon, who helped publish the book in England and to whom the volume, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was ultimately dedicated. The Wheatleys actually sent Phillis to London in 1773 with their son to oversee the publication of her poems, and while there she garnered fame and success, and met such prominent individuals as Benjamin Franklin and English abolitionist Granville Sharp. An invitation to meet King George III had to be declined due to Wheatley’s being summoned back to America due to Susanna’s poor health. As a free woman, Wheatley stayed in the United States for the rest of her life, living in poor health and poverty, yet continuing to write. She died in childbirth at around the age of 31, having born no children who survived. While many details of her life remain uncertain, her work continues to be studied and celebrated. A selection of her written works can be accessed here.

Powell poses Wheatley as an icon for Black women in poetry in her set of three songs, writing, “I thought it befitting to title the work Miss Wheatley’s Garden in honor of Phyllis [sic] Wheatley whose works are the garden in which many generations of African-American women poets have blossomed.”[2] The poets who blossomed in Wheatley’s garden include Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Angelina Weld Grimké, and Georgia Douglas Johnson, whose words Powell sets to music in this work. The texts of Grimké and Harper, “I Want to Die While You Love Me” and “Songs for the People,” respectively, can be heard in the upcoming concert.

We hope you will join us on Wednesday, April 19 for an afternoon of celebrating African-American women from Christine Anderson and friends for the final installment of our 2022–2023 Beyond the Notes concert series.

By Kaitlyn Canneto and Becca Fülöp

[1] Wheatley, Phillis. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London: A. Bell, 1773.

[2] Powell, Rosephanye. “Miss Wheatley’s Garden.” rosephanyepowerll.com. Accessed April 14, 2023. https://www.rosephanyepowell.com/art-songs/miss-wheatleys-garden/.

References:

Castellanos, Caroline. “Wheatley, Phillis (1753–1784).” In Encyclopedia of Free Blacks and People of Color in the Americas, by Stewart R. King. Facts On File, 2012. Accessed April 12, 2023.

Lynn, Carole. “Wheatley, Phillis (1753 84).” In The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of the American Enlightenment, edited by Mark Spencer. Bloomsbury, 2014. Accessed April 12, 2023.

Smith, Cassander L. “Phillis Wheatley.” In Great Lives From History: American Women. [N.p.]: Salem Press, 2016. Accessed April 12, 2023.

Wheatley, Phillis. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London: A. Bell, 1773.