The Guitar Studio of Allen Krantz presents Music of Bach and Vivaldi

Rescheduled!

Thursday, March 29th, 2018 | 12:00–12:50 PM | Paley Library Lecture Hall

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

Program

Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685–1750 | Cello Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008 (selected movements) • Invention No. 1 in C major, BWV 772 • Cello Suite No. 3 in C major, BWV 1009 (selected movements) • Invention No. 4 in D minor, BWV 775 • Lute Suite No. 3 in G minor, BWV 995 (selected movements)

Antonio Vivaldi, 1678–1741 | Trio Sonata in C major, RV 82

Performers | David D’Arville • Peter Deleplane • Andrew DiGiandomenico • Corin Duey • Andrew Evans • Emanuel Lozada-Mendez

Authenticity. In our time, both the word and its web of meanings have risen to exalted and desirous status. Social media accounts should reflect the quintessence of one’s genuine self, and corporations have seized upon authenticity as a modus operandi for branding and selling. Though their individual audiences and aims differ, this chorus of digital and commercial voices sings roughly the same refrain: be honest, be transparent, be original, be innovative, be unique.

Even before it became a contemporary cultural rubric, authenticity served as a touchstone for performances and recordings of Western classical music. In the late twentieth century, a steady supply of scholarship about centuries-old performance practices—what the British cleverly call HIP, or historically-informed performance—fed a growing appetite for authentic recordings that utilized, among others, authentic editions and authentic early instruments (in the form of meticulous copies of surviving artifacts) playing in authentic spaces with authentic pitch standards and temperaments.

While the movement opened our collective imagination to long-forgotten sounds, it also formed skirmish lines that drew zealous scholars, practitioners, and consumers into conflict. These battlefield remnants are preserved in books and articles that emerged as authenticity fever spiked. Raymond Leppard’s Authenticity in Music (1988), Authenticity and Early Music: A Symposium (1988), Peter le Huray’s Authenticity in Performance (1990), and Peter Kivy’s Authenticities: Philosophical Reflections on Music (1995) are a small sampling of many that come to mind. Though these remain informative and influential publications, the tenor of performance practice scholarship has moved in a more nuanced direction: debates about what a musical work was or is have yielded to contextual considerations about what it meant or means. Readers of books such as Bruce Haynes’s The End of Early Music: A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century (2007) and The Pathetick Musician: Moving an Audience in the Age of Eloquence (2016) by Haynes and Geoffrey Burgess are presented with an assortment of ideas and options rather than a set of prix fixe, “purist” directives.

Ironically, the most unreliable facet of the authenticity movement was the retrospective projection of its values onto musicians who thought in terms of flexibility, adaptation, and repurposing. This was the world of the Baroque musician: keyboardists were expected to improvise accompaniments from figured bass lines; singers and instrumentalists were expected to embellish their parts with ornaments; a cantata movement could be refitted with a new text for a different occasion, or even be rearranged as a stand-alone instrumental work. All of these were customary practices for J. S. Bach who, in the words of musicologist Werner Breig, found delight in exploring “the possibilities inherent in a finished work.” Breig further observes that “at every period of his creative life Bach may be found altering, arranging, and continuing to develop his own and other composers’ works” (the American Bach Society will take up this topic at its April 2018 gathering in New Haven, Connecticut, under the banner “Bach Re-Worked—Parody, Transcription, Adaptation”).

The concepts of fixed, finished, or authentic were largely unknown to Bach. And even if he did know them, his working methods suggest—quite assertively, in fact—that he would have ignored their conceptual and impractical limitations. Moreover, Bach was required to perform concerto transcriptions at the keyboard during his tenure as Weimar court organist, a function that resulted in the production of at least twenty such works between 1713 and 1714 alone! Writing about authenticity and Bach, musicologist Thomas Forrest Kelly reminds us that even “if we really did it Bach’s way, there would be nothing of ourselves in the matter,” adding: “the thing that mattered most of Bach, and probably to almost anybody else, is the presence of a musician.”

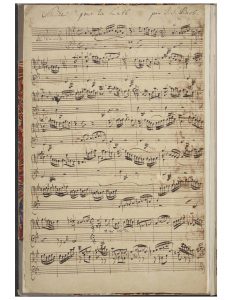

The six guitarists from the studio of Allen Krantz who will offer this Bach birthday program—he was born March 21, 1685—not only embody the Baroque spirit of adaptation by playing keyboard and cello works on the modern guitar, but also continue Bach’s own explorations in adapting his music for new contexts. Particularly noteworthy is the inclusion of movements from his lute suite, BWV 995, itself an adaptation of his own fifth solo cello suite, BWV 1011. Like its counterparts in the cello suites, the lute suite offers listeners an aural tour of various dances including a prélude in the French overture style, a fugue, an allemande, courante, a monodic yet highly expressive sarabande, two gavottes (the so-called galanterie movements), and a pleasantly lilting gigue.

Though Bach was not a lutenist—partially evidenced by his writing in staff notation rather than customary lute tablature—he was familiar with the instrument, its repertoire, and the virtuoso lutenists of his day. Lutes played at the first performance of the St. John Passion, BWV 245, in 1724, and Bach wrote at least three lute works after meeting the famed lutenist Sylvius Leopold Weiss in 1739. Among the many instruments cataloged in the estate inventory after Bach’s death was a single lute whose assessed value was roughly equivalent to three months’ wages for a carpenter living in 1725.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the guitar surpassed the lute as the plucked string instrument of choice. Though Michael Praetorius had once dismissed the guitar as an instrument of “charlatans and saltimbanques,” during the seventeenth century it gradually passed from the hands of street entertainers to the hands of courtiers and royalty, and even found its way into respectable domestic scenes such as the one shown here by Vermeer. The Baroque guitar’s lighter sonority—less resonant than its modern counterpart—and limited range made it a more ideal choice for accompanying songs and playing as part of an ensemble. Technological developments throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries increased the guitar’s facility for rendering the polyphonic stylings of Baroque music, allowing Bach’s solo instrumental works to become staples of the classical guitar repertoire.

As Bruce Haynes noted in the concluding chapter of The Pathetick Musician, Bach and his contemporaries provided musicians with adaptable scripts: performers were expected to take over from there. As these talented guitarists will demonstrate, to adapt this repertoire for new times and places is to engage in historically accurate—honest, faithful, and even authentic—practice. “And as our tastes change,” wrote Haynes, and as “Bach’s music and his world continue to speak to future generations, the journey will continue.”

So pause, pull up a chair, and enjoy some fine music—and birthday cake!—with us on Wednesday, March 21, or what would have been Bach’s 333rd birthday. The program begins at 12 PM and is free and open to the public.

References and Further Reading

Breig, Werner. “Composition as Arrangement and Adaptation.” In The Cambridge Companion to Bach, edited by John Butt, 154–170. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

David, Hans T. and Arthur Mendel, eds. The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. Revised and expanded by Christoph Wolff. New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1998.

Dolata, David. Meantone Temperaments on Lutes and Viols. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Haynes, Bruce. The End of Early Music: A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Haynes, Bruce, and Geoffrey Burgess. The Pathetick Musician: Moving an Audience in the Age of Eloquence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Heck, Thomas F., Harvey Turnbull, Paul Sparks, James Tyler, Tony Bacon, Oleg V. Timofeyev, and Gerhard Kubik. “Guitar.” Grove Music Online, accessed 7 March 2018.

Kelly, Thomas Forrest. Early Music: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Kenyon, Nicholas, ed. Authenticity and Early Music: A Symposium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Kivy, Peter. Authenticities: Philosophical Reflections on Musical Performance. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Le Huray, Peter. Authenticity in Performance: Eighteenth-Century Case Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Ledbetter, David. Unaccompanied Bach: Performing the Solo Works. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010.

Leppard, Raymond. Authenticity in Music. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1988.

Moore, J. Kenneth, Jayson Kerr Dobney, and E. Bradley Strauchen-Scherer. Musical Instruments: Highlights of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015.

Russell, Craig H. “Radical Innovations, Social Revolution, and the Baroque Guitar.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar, edited by Victor Anand Coelho, 153–181. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Tanenbaum, David. “Perspectives on the Classical Guitar in the Twentieth Century.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar, edited by Victor Anand Coelho, 182–206. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Chad Fothergill is a doctoral student in musicology at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance, and is the graduate assistant for the concert series, Beyond the Notes, at Temple University Libraries. He is also the editorial assistant for the journal Eighteenth-Century Music (Cambridge University Press). In addition to research and teaching, he remains active as an organist in solo, collaborative, and liturgical settings in the Philadelphia and New York City areas.

The series Beyond the Notes is supported by Temple University Libraries and Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance.