Charles Abramovic and students play music for piano by Scriabin, Schubert, Mozart, Brahms, Dvořák, Schnittke, and Abramovic

Wednesday, November 15, 2017 | 12:00–12:50 PM | Paley Library Lecture Hall

Light refreshments served. Boyer recital credit given.

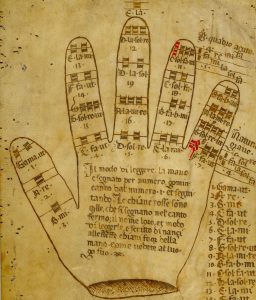

The hand: physiologists have supplied names for its many muscles—flexor digiti minimi, adductor pollicis, and lumbricals, among others—and pedagogues have assigned numbers to its digits—1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. We use it to make gestures associated with body language and sign language. It’s used in figures of speech and idioms: situations can get out of hand, we can try our hands at a new task, hand over hand-me-downs to a secondhand store, and take matters into our own hands. An eleventh-century monk named Guido used it to teach sight-singing with solfège syllables. Frustrated with a music theorist? Tell her or him to speak to the “Guidonian Hand”!

Even though hands are essential to virtually all forms of musicking (singers communicate through both voice and gesture), their musical prowess is often instinctively associated with those who play keyboard instruments. The hands of pianists have, in particular, received special scrutiny. Recalling his first encounter with Beethoven, Carl Czerny wrote of the elder composer’s hands “overgrown with hair,” and the son of pianist Ignaz Moscheles marveled at Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s “long, chord-grasping fingers.” When Chopin died in October 1849, the French painter and sculptor Auguste Clésinger made a death mask as well as cast of the composer’s hands. But not even death could stem the power of some hands: in the 1946 mystery horror film, The Beast with Five Fingers, a recently deceased pianist’s hand escapes from his mausoleum and terrorizes those who had wronged him!

Though it is natural to think of the piano as a two-handed instrument, its vast repertoire includes solo compositions, chamber works, and concertos for a single hand, two players with four hands, and three players with six hands. In case you were wondering, the detached left hand in The Beast with Five Fingers was fond of playing Brahms’s transcription of J. S. Bach’s chaconne from the second violin partita in D minor, BWV 1004. Some of these pieces—Scriabin’s Prelude and Nocturne, Op. 9, for left hand—certainly sound as if they are rendered with two hands, that is, until one actually experiences them in live performance such as Yuja Wang’s characteristically exquisite playing of the Prelude. Others are more poignant, such as this solo left-hand work composed for Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer after a stroke rendered him unable to use his right hand (Tranströmer himself plays while his poem “Allegro” is read by a narrator; this was recorded only a few weeks before his death in March 2015).

For musical connoisseurs of the nineteenth century, four-handed playing was especially popular both in real life and throughout literature. In Four-Handed Monsters: Four-Hand Piano Playing and Nineteenth-Century Culture, author Adrian Daub describes the literary mechanics thus: “two people, two bodies on one piano that they are forced to share—it’s a scene that often presents itself as anything but innocent, half pas de deux, half poker game.” Though eighteenth-century composers such as Haydn and Mozart helped popularize domestic four-hand playing, the movement reached its zenith in the nineteenth century before yielding to concert-oriented works for two pianos in the twentieth century such as concertos by Poulenc, Stravinsky, and Vaughan Williams. In the absence of recordings, podcasts, and Spotify, nineteenth-century audiences (and many reviewers, too) became familiar with symphonies, opera overtures, and other pieces through these four-handed transcriptions. According to Daub, Mozart’s symphonies were issued in four-hand versions more than six times between 1852 and 1859. Reger transcribed some of Bach’s organ music for two pianos, Brahms himself transcribed his own symphonic movements, and Dvořák originally wrote his Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, for two pianos in 1878. Orchestral and four-hand versions often appeared simultaneously or in close succession, a common nineteenth-century practice.

Works for six (and occasionally eight) hands began to appear more frequently in the twentieth century even though Czerny had already laid the groundwork with his Fantaisie, Op. 17, and three more “brilliant” fantasies in his Les trois amateurs, Op. 741. Rachmaninoff penned a Waltz and a Romance—both in A major—for this trio of thirty fingers, but perhaps the most well-known work in this category is Alfred Schnittke’s Homage to Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich of 1979. Here, Schnittke—a musical alchemist fond of polystylism—develops a tripartite formula that fuses Shostakovich’s musical signature (the pitches D, E-flat, C, and B-natural), Prokofiev’s sense of propulsion, and Stravinsky’s penchant for polytonal clusters. According to one reviewer, the result is at once “humorous” and “diabolical”!

The creative juxtaposition of varied performance forces for a single instrument goes, so to speak, hand-in-hand with the creative inclinations and wide-ranging activities of Charles Abramovic, who has won critical acclaim for his international performances as a soloist, chamber musician, and collaborator with leading instrumentalists and singers. He has performed a vast repertoire not only on the piano, but also the harpsichord and fortepiano. And actively involved with contemporary music, he has also recorded works of Milton Babbitt, Joseph Schwantner, Gunther Schuller and others for Albany Records, CRI, Bridge, and Naxos.

Abramovic has taught at Temple since 1988 and is a fixture of Philadelphia’s musical life, performing with numerous organizations in the city. He is a core member of the Dolce Suono Ensemble, and performs often with Network for New Music and Orchestra 2001. In 1997 he received the Career Development Grant from the Philadelphia Musical Fund Society, and in 2003 received the Creative Achievement Award from Temple University. His teachers have included Natalie Phillips, Eleanor Sokoloff, Leon Fleisher, and Harvey Wedeen.

The November 15 performance by Abramovic and his students begins at 12:00 PM in the Paley Library lecture hall, 1210 West Berks Street. The program is free and open to the public.

References and Further Reading

Bozarth, George S., and Stephen H. Brady. “The Pianos of Johannes Brahms.” In Brahms and His World, Revised Edition, edited by Walter Frisch and Kevin C. Karnes, 73–93. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Daub, Adrian. Four-Handed Monsters: Four-Hand Piano Playing and Nineteenth-Century Culture. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Edel, Theodore. Piano Music for One Hand. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Ferguson, Howard. Keyboard Duets. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Hamilton, Kenneth. After the Golden Age: Romantic Pianism and Modern Performance. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Kinderman, William. “Schubert’s Piano Music: Probing the Human Condition.” In The Cambridge Companion to Schubert, edited by Christopher H. Gibbs, 155–173. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Loesser, Arthur. Men, Women, and Pianos: A Social History. New York: Dover, 1990.

Lubin, Ernst. The Piano Duet. New York: Grossman, 1970.

Roberge, Marc-André. “From Orchestra to Piano: Major Composers as Authors of Piano Reductions of Other Composers’ Works.” Notes 49.3 (March 1993): 925–936.

Rowland, David, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Piano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Small, Christopher. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1998.

Todd, R. Larry, ed. Nineteenth-Century Piano Music. New York: Schirmer, 1990.

Chad Fothergill is a doctoral student in musicology at Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance, and is the graduate assistant for the concert series, Beyond the Notes, at Temple University Libraries. He is also the editorial assistant for the journal Eighteenth-Century Music (Cambridge University Press). In addition to research and teaching, he remains active as an organist in solo, collaborative, and liturgical settings in the Philadelphia and New York City areas. He may be reached at chad.fothergill@temple.edu.

The series Beyond the Notes is supported by Temple University Libraries and Temple University’s Boyer College of Music and Dance.

One response to “Music for One, Two, Four, Six Hands”

First off I would like to say fantastic blog! I had a quick question that I’d like to ask if you don’t mind.

I was interested to find out how you center yourself and clear your mind before writing.

I have had difficulty clearing my thoughts in getting my ideas out there.

I truly do enjoy writing however it just seems like the

first 10 to 15 minutes are generally wasted just trying to figure out

how to begin. Any suggestions or tips? Kudos!